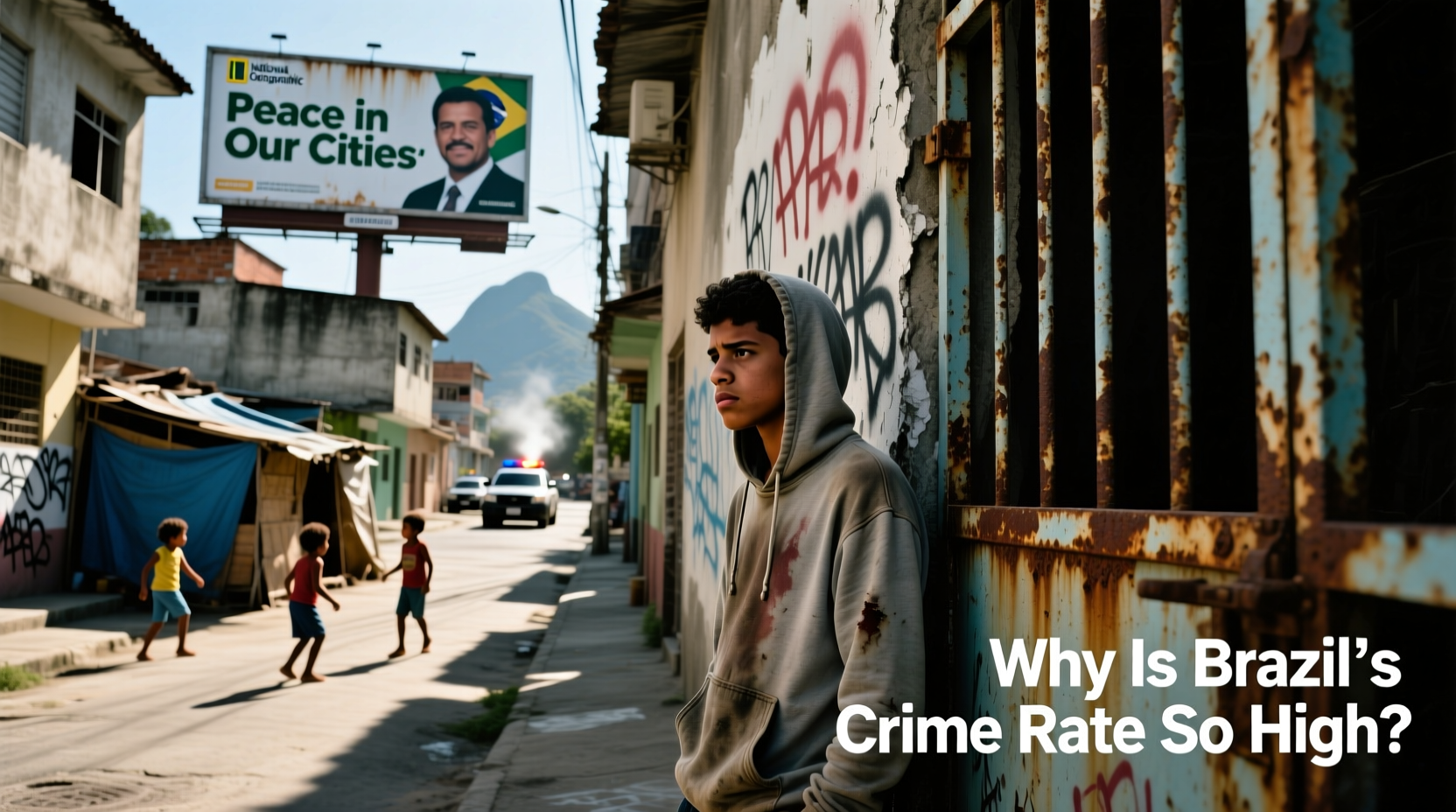

Brazil consistently ranks among the countries with the highest homicide rates in the world. Despite economic growth and social progress over the past decades, violent crime remains deeply entrenched in many urban centers and marginalized communities. Understanding why Brazil’s crime rate remains so high requires examining a complex web of socioeconomic, institutional, and cultural forces. This article breaks down the most significant contributing factors, supported by data, expert insights, and real-world examples, offering a clear picture of the roots of violence and potential pathways toward reform.

Economic Inequality and Social Exclusion

One of the most powerful drivers of crime in Brazil is its extreme level of income inequality. The country has long ranked among the most unequal in the world, with vast disparities between wealthy elites and impoverished populations. According to the World Bank, Brazil’s Gini coefficient—measuring income distribution—remains above 0.5, where 0 represents perfect equality and 1 represents maximum inequality.

This imbalance fuels resentment, limits opportunity, and creates environments where crime becomes a survival mechanism. In favelas (informal settlements), youth often face limited access to quality education, healthcare, and formal employment. When legitimate avenues for advancement are blocked, illicit economies such as drug trafficking and armed robbery become more appealing.

Urban Segregation and Geographic Vulnerability

Brazil’s cities are sharply divided along class and racial lines. Wealthy neighborhoods are often walled, gated, and protected by private security, while poor communities—especially in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo—are left under-resourced and vulnerable. This spatial segregation reinforces cycles of violence.

The concentration of poverty in isolated pockets allows criminal organizations to exert control with little resistance. In many favelas, police presence is sporadic or hostile, leading residents to rely on or tolerate local gangs that provide informal governance, albeit through coercion and fear.

A telling example is the Complexo do Alemão in Rio, where for years armed factions operated openly, running extortion schemes and controlling movement in and out of the area. Even after military-style police operations, stability remains fragile due to lack of follow-up social investment.

“Violence in Brazil isn’t random—it follows the geography of neglect.” — Dr. Camila Nunes Dias, Urban Sociologist, University of São Paulo

Gang Activity and Organized Crime Networks

Organized crime groups like the Primeiro Comando da Capital (PCC) and Comando Vermelho (CV) have evolved into sophisticated enterprises with influence across prisons, slums, and even political systems. These groups control drug distribution networks, engage in arms trafficking, and orchestrate prison riots to assert power.

The PCC, originally formed in São Paulo prisons in the 1990s, now operates in nearly every Brazilian state and has expanded into international drug routes. Its ability to maintain internal discipline and exploit systemic weaknesses makes it a formidable force beyond law enforcement’s reach.

Gangs also recruit heavily from disenfranchised youth, offering money, status, and protection in exchange for loyalty. In some cases, entire families become entangled in these networks, making disengagement extremely difficult.

| Criminal Organization | Origin | Estimated Members | Primary Activities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primeiro Comando da Capital (PCC) | São Paulo (1993) | 30,000+ | Drug trafficking, prison control, money laundering |

| Comando Vermelho (CV) | Rio de Janeiro (1970s) | 25,000+ | Street-level drug sales, territorial control |

| Terceiro Comando Puro (TCP) | Rio de Janeiro (1990s) | 5,000+ | Rivalry-based violence, local extortion |

Police Violence and Institutional Weakness

While Brazil spends significantly on public security, results remain poor due to corruption, inefficiency, and human rights abuses. Police forces are often undertrained, poorly equipped, and embedded in cultures of impunity. Extrajudicial killings by police are alarmingly common—over 6,400 people were killed by police in Brazil in 2022 alone, according to the Brazilian Forum on Public Security.

This aggressive approach alienates communities and undermines trust. Residents in high-crime areas frequently view the police not as protectors but as threats. As a result, cooperation with investigations is minimal, allowing criminals to operate with fewer witnesses and less accountability.

Judicial delays further weaken deterrence. The average time to resolve a criminal case in Brazil exceeds five years, meaning most offenders never face timely consequences. Overcrowded prisons also exacerbate the problem—many detainees await trial for months or years in conditions that foster radicalization and gang recruitment.

Historical Roots and Systemic Neglect

The roots of Brazil’s crime crisis extend back centuries. Colonial-era land concentration, slavery, and exclusionary policies laid the foundation for deep social fractures. Post-abolition in 1888, millions of freed Black Brazilians were left without land, education, or integration into the economy—inequities that persist today.

In the 20th century, rapid urbanization without adequate planning led to sprawling informal settlements lacking basic infrastructure. Governments responded with repression rather than inclusion, normalizing heavy-handed policing over social development.

Even during periods of democratic reform, such as the 1988 Constitution that guaranteed broad civil rights, implementation faltered due to bureaucratic inertia and elite resistance to redistribution. As one study from the Inter-American Development Bank notes, “Brazil invests less than 1% of GDP in preventive social programs despite spending heavily on reactive security.”

Mini Case Study: Pacifying Police Units (UPPs) in Rio de Janeiro

In the late 2000s, Rio launched the UPP program—a strategy to reclaim favelas from gangs by establishing permanent, community-oriented police posts. Initially successful in reducing violence in areas like Santa Marta, the initiative eventually unraveled.

Over time, UPP officers became isolated, under-supported, and susceptible to corruption. Community trust eroded when abuses went unpunished. By the mid-2010s, many units had withdrawn or lost control, and gang violence returned with greater intensity.

The UPP experiment illustrates a critical lesson: security interventions fail without sustained investment in social services, transparency, and civilian oversight.

Checklist: Key Factors Behind Brazil’s High Crime Rate

- Severe income inequality limiting upward mobility

- Geographic segregation concentrating poverty and violence

- Powerful organized crime networks with national reach

- Underfunded and corrupt public institutions

- Police violence undermining community trust

- Slow judicial system enabling impunity

- Lack of investment in education and youth programs

- Historical marginalization of Afro-Brazilian and low-income populations

- Inadequate prison reform and overcrowding

- Weak coordination between federal, state, and municipal agencies

Frequently Asked Questions

Is tourism in Brazil unsafe due to crime?

While violent crime is concentrated in specific low-income neighborhoods, tourists in major cities like Rio or Salvador should remain cautious, especially at night and in isolated areas. Most tourist zones are heavily patrolled, but petty theft and opportunistic crime occur. Staying informed and avoiding high-risk areas reduces risk significantly.

Why doesn’t more policing reduce crime?

Heavy-handed policing without community engagement often increases tension and drives crime underground rather than eliminating it. Without addressing root causes like poverty and lack of opportunity, arrests and raids offer only temporary suppression, not lasting safety.

Are there any successful crime reduction programs in Brazil?

Yes. Cities like Curitiba and Florianópolis have lower homicide rates due to integrated approaches combining urban planning, education, and community policing. Programs like “Saúde e Cidadania” in Minas Gerais reduced youth violence by linking at-risk teens with mental health services and job training.

Conclusion: Toward a Safer Future

Brazil’s high crime rate is not inevitable. It is the outcome of decades of structural neglect, unequal development, and misplaced priorities in public security. While no single solution exists, evidence shows that sustainable reductions in violence come from investing in people—not just prisons.

Rebuilding trust between citizens and institutions, expanding access to education and jobs, reforming the justice system, and holding security forces accountable are all essential steps. Change will require political courage and long-term commitment, but the alternative—continued cycles of violence and despair—is far costlier.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?