Corned beef’s vibrant red hue often surprises people unfamiliar with its preparation. Unlike fresh beef, which turns brown when cooked, corned beef retains a deep pink or ruby-red color even after hours of simmering. This isn’t artificial coloring or a trick of the light—it’s science. The redness is the result of a precise curing process involving salt, nitrites, and time. Understanding this transformation reveals not only how food chemistry shapes what we eat but also why traditional methods endure in modern kitchens.

The Role of Curing Salt in Color Development

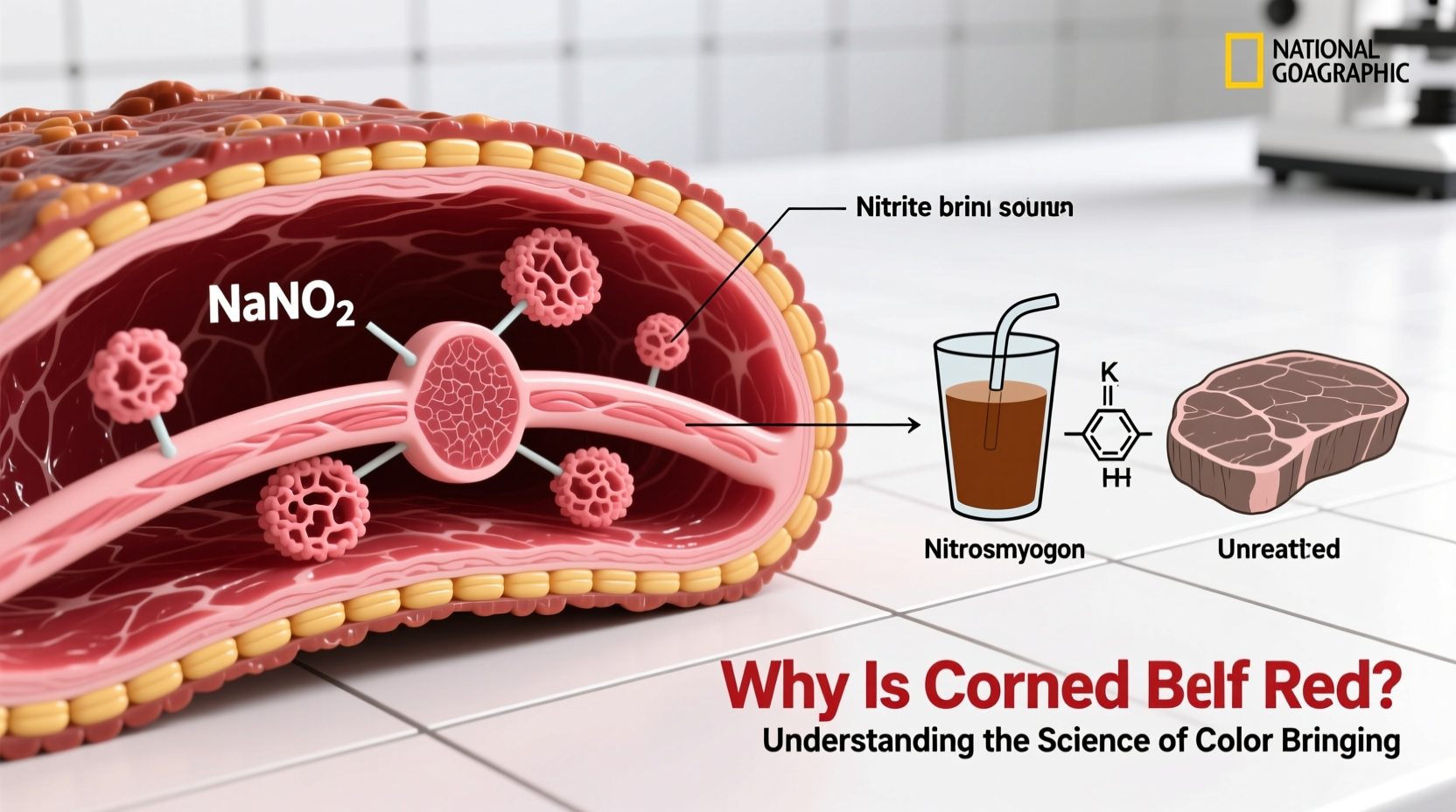

The most critical factor behind corned beef’s red color is the use of curing salt—specifically sodium nitrite. While regular table salt (sodium chloride) preserves and seasons the meat, it doesn’t prevent oxidation that turns myoglobin (the protein responsible for meat’s color) brown during cooking. Curing salt, often labeled as \"pink salt\" or “Prague powder #1,” contains sodium nitrite, which chemically alters myoglobin to form nitrosomyoglobin.

Nitrosomyoglobin is stable and heat-resistant, meaning it maintains a bright red or pink appearance even at high temperatures. During the cooking process, this compound further transforms into nitrosohemochrome, which gives cooked corned beef its characteristic rosy tint. Without nitrite, the meat would resemble stewed beef—grayish-brown and less visually striking.

“Nitrites don’t just preserve flavor and safety—they define the identity of cured meats like corned beef. That red color signals authenticity to consumers.” — Dr. Laura Simmons, Food Scientist and Meat Preservation Specialist

Brining: The Science Behind the Soak

Brining is more than soaking meat in liquid—it's an osmotic exchange that infuses flavor, moisture, and preservatives deep into the muscle fibers. For corned beef, the brine typically includes water, coarse salt, sugar, bay leaves, peppercorns, and crucially, sodium nitrite. The term “corned” itself refers to the large “kernels” or grains of salt historically used to cure beef before refrigeration.

The brining process lasts between 5 to 10 days, depending on the size of the brisket. Over this period, the salt and nitrites diffuse into the meat, inhibiting bacterial growth while modifying the protein structure. This diffusion stabilizes the color and enhances tenderness by partially denaturing proteins, allowing them to retain more water during cooking.

Key Components of a Traditional Corned Beef Brine

| Ingredient | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Sodium Chloride (Salt) | Preserves, seasons, draws out moisture initially then pulls brine back in |

| Sodium Nitrite | Fixes color, prevents botulism, extends shelf life |

| Sugar (brown or white) | Balances saltiness, aids in penetration, promotes mild browning |

| Spices (peppercorns, mustard seed, coriander) | Adds flavor complexity |

| Water | Carrier medium for solubilized ingredients |

Myoglobin Transformation: From Red to Pink and Back Again

To fully grasp why corned beef stays red, one must understand myoglobin—the oxygen-storing protein in muscle tissue. In raw beef, myoglobin is purple-red (deoxymyoglobin). When exposed to air, it becomes oxymyoglobin, giving fresh cuts their cherry-red surface. Cooking normally converts it to metmyoglobin, which is gray-brown.

In corned beef, however, nitric oxide from decomposed nitrite binds tightly to myoglobin, forming a stable complex resistant to thermal degradation. This complex reflects light differently, appearing pink-red both raw and cooked. Even when sliced and exposed to air, properly cured corned beef resists discoloration far longer than uncured meat.

It’s worth noting that some commercial producers use celery juice powder—a natural source of nitrates—as a “clean label” alternative. However, under the right conditions (presence of bacterial cultures), these nitrates convert to nitrites just like synthetic ones. The end result? Identical color chemistry, despite marketing differences.

Step-by-Step: How Color Develops During the Curing Process

The journey from grayish-pink raw brisket to glossy red corned beef unfolds over days. Here’s a timeline showing how color evolves:

- Day 1: Brisket submerged in brine. Surface begins absorbing salt and nitrites; slight darkening may occur.

- Day 3: Nitrites penetrate deeper layers. Myoglobin starts converting to nitrosomyoglobin. Interior takes on faint pink tinge.

- Day 5–7: Full saturation achieved. Entire cut develops uniform pink-red hue. Brine may darken due to extracted blood pigments.

- Pre-Cook Rinse: Excess brine removed. Color remains intact beneath surface.

- During Cooking: Heat activates nitrosohemochrome formation. Meat becomes brighter, not duller. Steam may carry off residual salt, enhancing visual clarity.

- After Slicing: Freshly cut surfaces remain vivid pink. Minimal oxidation occurs over several hours if kept warm.

Common Misconceptions About the Red Color

Many assume the redness means the meat is raw or dyed. Neither is true. Some believe leftover red juice indicates blood, but it’s actually a mixture of water, myoglobin, and dissolved curing agents released during cooking. Blood is largely removed during slaughter; what remains contributes minimally to color.

Another myth is that all red-cured meats are unsafe due to nitrites. While excessive intake of processed meats has been linked to health concerns, the amounts used in proper curing are strictly regulated and serve essential antimicrobial functions. The U.S. Department of Agriculture limits sodium nitrite to 200 ppm in finished products—well below toxic levels.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is the red color in corned beef natural?

Yes. The color results from a natural chemical reaction between nitrites in the brine and myoglobin in the meat. No artificial dyes are needed to achieve the red hue, though some brands may add food coloring for consistency.

Can I make corned beef without curing salt?

You can, but it won't look or keep like traditional corned beef. Without nitrites, the meat will cook to a gray-brown color and have a shorter refrigerator life. It will taste similar but lack the distinctive appearance and texture associated with authentic corned beef.

Why do some packages say “uncured” if they still contain nitrites?

This labeling follows USDA guidelines. Products using celery powder instead of synthetic sodium nitrite can be labeled “no nitrates or nitrites added,” even though naturally occurring nitrates convert to nitrites during processing. Chemically, the outcome is nearly identical.

Real-World Example: A Home Curer’s Experience

When Sarah Thompson decided to make her first homemade corned beef, she skipped curing salt, fearing it was unhealthy. She brined a brisket for seven days using only sea salt, spices, and beet juice—believing the latter would mimic the red color. After boiling, the meat was tender and flavorful, but uniformly gray. Disappointed, she researched further and learned about nitrosomyoglobin formation. The next year, she used Prague powder #1 as directed. The difference stunned her guests: the slice revealed a consistent, appetizing pink center. “I finally understood—it wasn’t about dyeing meat. It was about chemistry,” she said.

Checklist: Ensuring Proper Color Development in Homemade Corned Beef

- Use curing salt containing sodium nitrite (e.g., Prague Powder #1)

- Maintain a refrigerated temperature (34–40°F / 1–4°C) during brining

- Allow at least 5–7 days for full penetration (longer for larger cuts)

- Ensure even contact by submerging meat completely and flipping daily

- Rinse well before cooking to reduce surface salt

- Cook slowly in moist heat (simmer, don’t boil rapidly)

- Test internal color after cooking—should be uniformly pink, not gray

Conclusion: Embrace the Science Behind the Hue

The red color of corned beef is far more than aesthetic—it’s a hallmark of successful curing, microbial safety, and culinary tradition. By understanding how brining and nitrites interact with meat proteins, cooks gain greater control over quality and consistency. Whether you're preparing it for St. Patrick’s Day or exploring charcuterie at home, appreciating the science behind the color transforms a simple meal into a lesson in food preservation and chemistry.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?