The United States capital, commonly referred to as Washington, D.C., stands apart from all 50 states—not just in function, but in identity. It doesn’t belong to any state, has no voting representation in Congress, and carries a name that blends symbolism with history: the District of Columbia. But why is it called that? The answer lies in early American politics, national pride, and a deliberate effort to create a federal space free from state control.

Understanding the origins of “District of Columbia” requires stepping back into the founding era of the United States, when the structure of government was being debated and shaped by figures like George Washington, James Madison, and Alexander Hamilton. The naming and creation of the capital were not arbitrary—they were deeply intentional decisions reflecting both practical governance and symbolic unity.

The Constitutional Foundation: A Federal Capital

The U.S. Constitution, ratified in 1788, laid the groundwork for a national capital outside the jurisdiction of any individual state. Article I, Section 8, Clause 17 grants Congress the power:

“The Congress shall have Power To exercise exclusive Legislation in all Cases whatsoever, over such District (not exceeding ten Miles square) as may, by Cession of particular States, and the Acceptance of Congress, become the Seat of the Government of the United States.”

This clause ensured that the federal government would have full authority over its own seat of power, preventing any single state from exerting undue influence over national affairs. The idea was to avoid conflicts of interest—such as a state hosting Congress while also participating in legislative debates—and to establish a neutral zone dedicated solely to federal operations.

The Naming of “Columbia”: Symbolism Over Geography

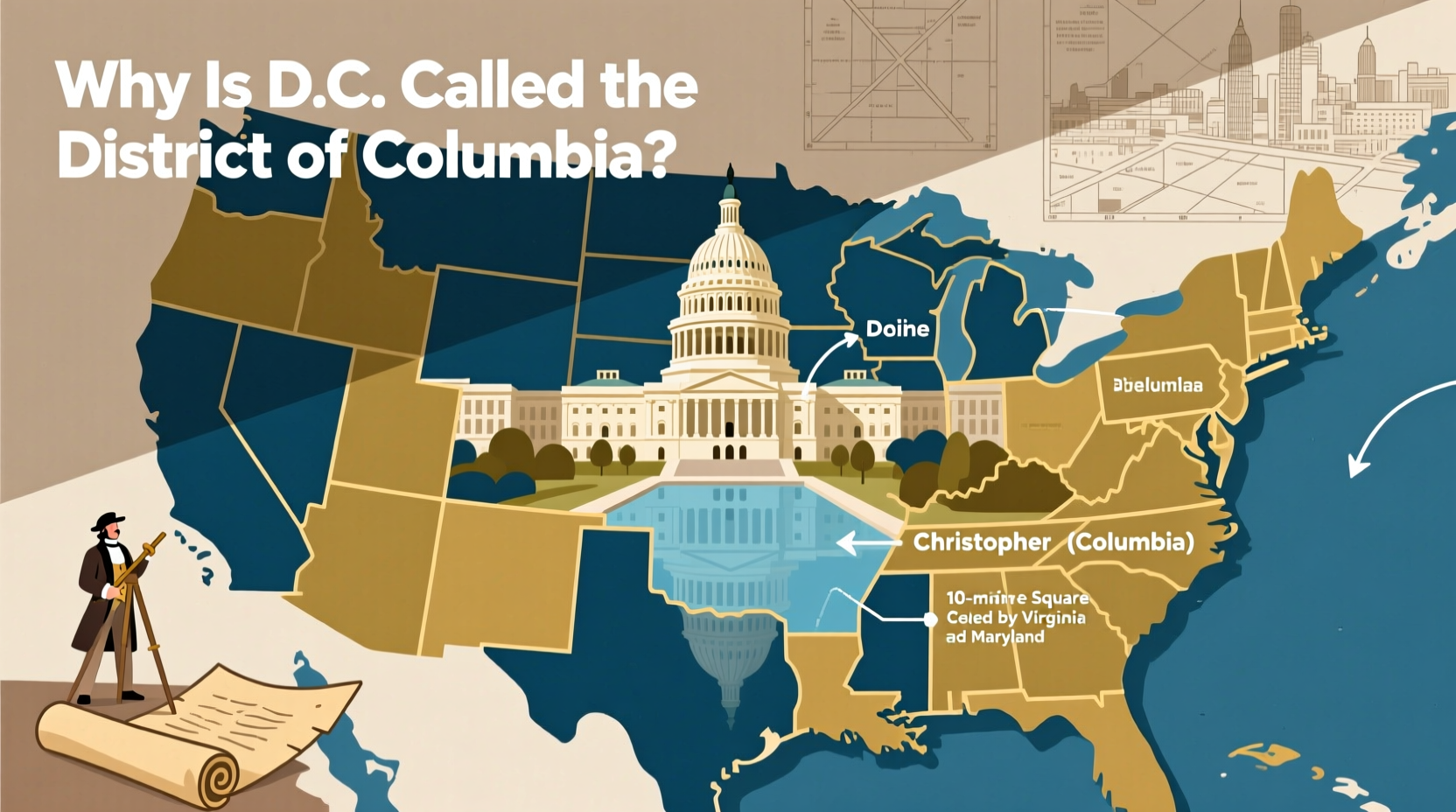

The term “Columbia” might sound like a reference to Colombia in South America, but it predates that country’s existence. In fact, “Columbia” was a poetic and patriotic personification of the United States itself, derived from Christopher Columbus, whose voyages initiated European exploration of the Americas.

By the late 18th century, “Columbia” had become a widely used allegorical name for the New World and, later, for the United States. It appeared in poetry, political rhetoric, and even early American songs. For example, “Hail, Columbia,” written in 1798, served as an unofficial national anthem for decades.

When the federal district was established in 1790, naming it the “District of Columbia” was a way to honor this symbolic identity—elevating the capital beyond mere geography to represent the ideals of the young republic.

The Residence Act of 1790: Creating the District

The formal creation of Washington, D.C., began with the Residence Act of 1790, passed by Congress and signed by President George Washington. This legislation authorized the establishment of a permanent national capital along the Potomac River.

The location was the result of political compromise. Northern states, led by Alexander Hamilton, wanted the federal government to assume Revolutionary War debts incurred by the states. Southern states, led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, resisted unless the capital was placed in a more southern, agrarian region. The compromise—known as the Dinner Table Bargain—allowed Hamilton’s financial plan to move forward in exchange for placing the capital in the South.

Congress selected a 100-square-mile diamond-shaped area along the Potomac, ceded by Maryland and Virginia. George Washington personally oversaw the surveying and planning of the city, which was named in his honor. The entire federal enclave became officially known as the District of Columbia.

Timeline of Key Events

- 1783: Continental Congress is forced to flee Philadelphia due to unpaid soldiers, highlighting the need for a secure, independent capital.

- 1787: Constitutional Convention includes provision for a federal district.

- 1790: Residence Act passes; Washington selects the site.

- 1791: City of Washington is formally named and planned by Pierre Charles L’Enfant.

- 1801: The District of Columbia Organic Act places the capital under direct federal control.

- 1846: The portion of the district originally ceded by Virginia is returned to the state, shaping today’s borders.

Washington vs. the District of Columbia: What’s the Difference?

A common point of confusion is the relationship between “Washington” and “the District of Columbia.” Legally, they are one and the same—but named differently for different purposes.

- Washington refers to the city—the urban center designed by L’Enfant, home to the White House, Capitol, and federal agencies.

- District of Columbia refers to the entire federal territory, including residential neighborhoods, parks, and administrative zones.

Together, they form “Washington, District of Columbia,” abbreviated as “Washington, D.C.”—a designation that distinguishes it from Washington State, which wasn’t admitted to the Union until 1889.

Do’s and Don’ts When Referring to the Capital

| Do | Don’t |

|---|---|

| Say “Washington, D.C.” when clarity is needed. | Call it “Washington State” or assume it’s part of Maryland or Virginia. |

| Use “D.C.” informally in context (e.g., “I work in D.C.”). | Refer to it as a state or claim it has voting senators. |

| Recognize that residents pay federal taxes but lack full congressional representation. | Assume D.C. residents have the same rights as those in the 50 states. |

Modern Implications: Identity and Representation

Over two centuries later, the District of Columbia remains a unique political entity. While it functions like a city—with a mayor, city council, and local services—it lacks full autonomy. Congress retains the power to override local laws, and D.C. has no voting representatives in the Senate or House of Representatives.

This has sparked ongoing debate about D.C. statehood. Advocates argue that the more than 700,000 residents deserve equal representation, especially since they pay federal taxes. Opponents cite constitutional concerns about creating a state from the seat of government.

“D.C. is the only place in the U.S. where citizens are taxed without full representation. That’s fundamentally at odds with American democratic values.” — Dr. Lena Peterson, Constitutional Historian, Georgetown University

Mini Case Study: The Push for D.C. Statehood

In 2020, the U.S. House of Representatives passed H.R. 51, a bill to admit “Washington, Douglass Commonwealth” as the 51st state. The proposal honors Frederick Douglass, who lived in D.C. and advocated for civil rights. Though the bill stalled in the Senate, it highlighted growing public support for change. Proponents note that D.C. has a larger population than Wyoming and Vermont, yet those states each have two senators while D.C. has none.

The debate continues to center on the original intent of the District of Columbia: Was it meant to be a temporary administrative zone, or a permanent exclusion of citizen rights in the name of federal neutrality?

Frequently Asked Questions

Why isn’t Washington, D.C. part of any state?

To ensure federal independence, the Founding Fathers created a capital outside state control. This prevents any single state from influencing national legislation or hosting the government for political leverage.

Can residents of D.C. vote for president?

Yes. Under the 23rd Amendment (1961), D.C. residents can vote in presidential elections and are allocated electoral votes as if they were a state—though limited to no more than the least populous state (currently three votes).

Has the size of D.C. changed since 1790?

Yes. Originally, the district included land on both sides of the Potomac River, ceded by Virginia and Maryland. In 1846, Congress returned the Virginia portion (modern-day Arlington and Alexandria) due to neglect and low tax revenue. Today’s D.C. borders reflect only the Maryland cession.

Conclusion: A Name Steeped in Purpose and Legacy

The name “District of Columbia” is more than a label—it’s a reflection of America’s founding principles. It combines geographic necessity with symbolic patriotism, honoring both the man who led the nation into independence and the ideal of a unified republic.

From the Residence Act to modern statehood debates, the story of D.C. continues to evolve. Understanding why it’s called the District of Columbia offers insight not just into a place, but into the enduring tension between federal power and civic rights.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?