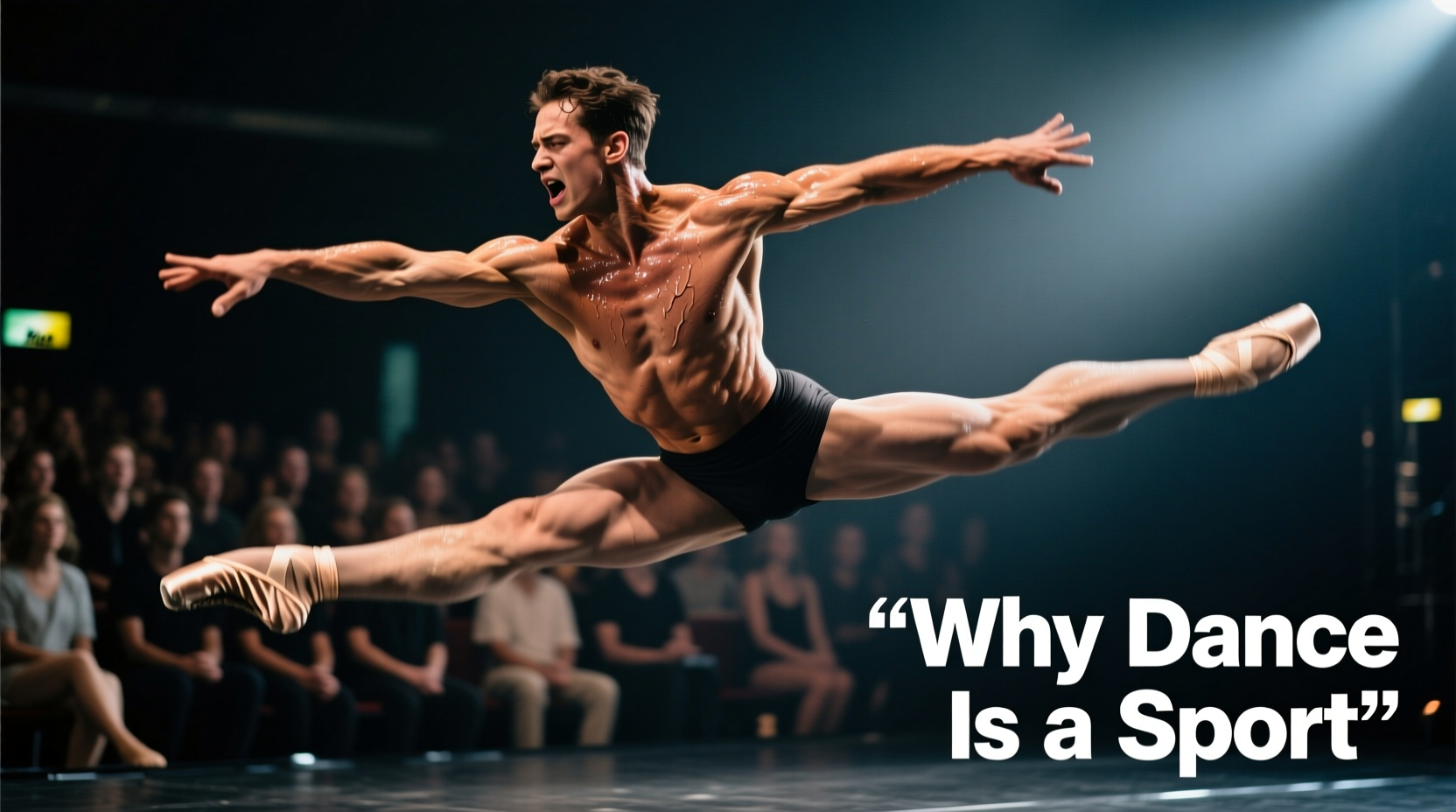

Dance has long occupied a complex space between art and athleticism. While widely celebrated for its expressive beauty, many dancers and sports scientists argue that dance meets—and often exceeds—the physical criteria of traditional sports. The debate over whether dance qualifies as a sport centers on definitions of athleticism, training intensity, and competitive structure. When examined through the lens of physical demand, endurance, injury risk, and performance under pressure, dance emerges not just as performance art but as a discipline that rivals even elite athletic pursuits.

The Physical Rigor of Dance: More Than Just Movement

Dancers undergo training regimens comparable to those of Olympic athletes. A professional dancer’s day typically includes multiple hours of technique classes, rehearsals, strength conditioning, and flexibility work. Ballet dancers, for example, execute movements that require extreme muscular control, balance, and joint stability—often landing jumps with forces up to 12 times their body weight. Contemporary and hip-hop dancers face similar demands, combining explosive power with precision timing and spatial awareness.

Research from the Journal of Dance Medicine & Science shows that elite dancers exhibit cardiovascular fitness levels on par with runners and cyclists. A study tracking heart rates during performances found sustained exertion in the 70–85% maximum heart rate zone—well within the aerobic training threshold recommended for athletes.

Muscular Endurance and Strength Requirements

Dance requires exceptional muscular endurance. Dancers must sustain controlled movement for extended periods, often without breaks. Unlike most sports where rest occurs between plays or sets, dance performances demand continuous motion for 10 to 30 minutes or more. This places significant strain on slow-twitch muscle fibers and core stabilizers.

Strength is equally critical. Lifting partners in ballroom or contemporary routines demands upper-body power, while maintaining turnout in ballet activates deep hip rotators and glutes. A single pirouette involves precise coordination between the core, legs, and inner ear—balancing biomechanics at high speed.

Injury Rates Comparable to Contact Sports

If dance were judged solely by injury statistics, it would unquestionably rank among high-risk sports. According to the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, up to 90% of professional dancers suffer an injury each year, with overuse injuries being the most common. Ankle sprains, stress fractures, tendonitis, and lower back pain are prevalent—mirroring issues seen in gymnasts, soccer players, and football athletes.

A longitudinal study at the University of Wolverhampton found that competitive dancers reported injury rates per 1,000 hours of exposure higher than rugby and basketball players. Yet, unlike traditional sports, dance rarely receives equivalent access to athletic trainers, insurance coverage, or medical support systems.

“Dance is one of the most physically punishing disciplines I’ve worked with. The combination of repetition, impact, and aesthetic perfection creates a perfect storm for injury.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Sports Physiotherapist and Dance Medicine Specialist

Training Hours and Competitive Pressure

Dancers often begin training before age 10 and accumulate thousands of hours of practice before turning professional. A typical pre-professional dancer trains 15–25 hours per week outside of academic school, increasing to 35+ hours during competition seasons. This volume rivals that of young athletes in swimming, tennis, or figure skating.

Competitive dance, especially in styles like ballroom, rhythmic gymnastics (recognized by the IOC), or street dance battles, features formal judging panels, scoring systems, and qualifying rounds—hallmarks of organized sport. Competitors train for months to master routines scored on technical execution, synchronization, difficulty, and artistic impression.

Is Dance a Sport? Breaking Down the Debate

The resistance to classifying dance as a sport often stems from cultural perceptions. Because dance emphasizes creativity, music, and emotional expression, it is frequently categorized solely as performing art. However, this overlooks the fact that many recognized sports—such as figure skating, diving, and gymnastics—also blend aesthetics with athletic skill.

Sports historian Dr. Marcus Reed notes: “We accept synchronized swimming and ski jumping with style scores, yet we hesitate to grant dance the same legitimacy. The bias reflects outdated hierarchies between mind/body and art/athleticism.”

International organizations have begun to recognize dance’s athletic nature. The World DanceSport Federation (WDSF) governs competitive ballroom under the International Olympic Committee’s recognition, having applied for full Olympic status. Breaking, a dynamic form of street dance, will debut as an official Olympic sport at the 2024 Paris Games—a landmark acknowledgment of dance as competitive sport.

Arguments Against Dance as a Sport

- Lack of standardized rules: Unlike soccer or basketball, dance competitions vary widely in format and scoring.

- Subjective judging: Emphasis on artistry introduces subjectivity, though this also exists in gymnastics and ice skating.

- No direct opponent: Dance lacks head-to-head competition, though neither do track events or archery.

Yet these points don’t negate athleticism—they highlight differences in structure, not substance.

Physical Demands Compared: Dance vs. Traditional Sports

| Attribute | Dance (Ballet/Contemporary) | Gymnastics | Soccer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weekly Training Hours | 25–40 | 20–35 | 15–25 |

| Max Heart Rate During Performance | 75–85% | 80–90% | 85–95% |

| Common Injuries | Stress fractures, tendonitis, ankle sprains | Wrist sprains, ACL tears, spondylolysis | ACL tears, hamstring strains, concussions |

| Years to Elite Level | 10–15 | 8–12 | 8–10 |

| Competition Format | Scored routines | Scored routines | Team match |

The table illustrates that dance aligns closely with established sports in training load, physical strain, and injury profile. What differentiates it is presentation—not performance capacity.

Mini Case Study: From Studio to Stage – The Journey of a Competitive Dancer

Maya Chen began dancing at age six. By 14, she was training 30 hours a week in jazz, tap, and lyrical styles while competing nationally. Her routine included morning conditioning, two dance classes, afternoon rehearsal, and evening stretching and physiotherapy. At 17, she suffered a stress fracture in her metatarsal due to overtraining—a setback requiring eight weeks off her feet.

After recovery, Maya worked with a sports nutritionist and added cross-training to prevent re-injury. She went on to win the junior division at the U.S. Open Dance Championships. “People say ‘you’re not an athlete, you just dance,’” she says. “But I train harder than most athletes I know. My body is my instrument and my engine.”

Her story reflects thousands of dancers who endure physical strain, mental pressure, and public scrutiny—all hallmarks of elite sport.

Actionable Checklist: Supporting Dance as Athletic Practice

- Educate schools and parents on dance’s physical demands.

- Integrate sports science into dance curricula (nutrition, recovery, kinesiology).

- Ensure dancers have access to athletic trainers and mental health support.

- Advocate for equal funding and facilities in academic and recreational programs.

- Promote media coverage that highlights dance’s athleticism, not just aesthetics.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is dance considered a sport in schools?

In many countries, including the U.S., dance is classified under physical education but often excluded from interscholastic athletics departments. Some states, like Florida and Texas, now recognize competitive dance teams as varsity sports, providing funding and eligibility for championships.

Can dancers be considered athletes?

Yes. Athletes are defined as individuals who train and compete in activities requiring physical skill and stamina. Dancers meet this definition unequivocally. Major institutions like Harvard and Stanford classify dance team members as student-athletes.

Why isn’t dance in the Olympics yet?

Breaking (breakdancing) will be included in the 2024 Paris Olympics. Other forms like ballet or contemporary aren’t structured for Olympic inclusion due to lack of global standardization. However, DanceSport (ballroom) has been a recognized Olympic discipline since 1997 and continues pursuing medal status.

Conclusion: Rethinking the Definition of Sport

The question isn't whether dance *should* be called a sport—it's whether our definition of sport is broad enough to include disciplines that demand extreme physical prowess, years of disciplined training, and peak performance under pressure. Dance fulfills every criterion of athleticism while adding layers of artistry that enrich rather than diminish its value.

Recognizing dance as a sport validates the dedication of millions of performers worldwide. It opens doors to better healthcare, equitable funding, and broader respect for their craft. As breaking takes center stage at the Olympics, the world is beginning to see what dancers have known all along: when your body moves with precision, power, and purpose, it doesn’t matter if you’re on a stage or a field—you’re an athlete.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?