The term “venison” evokes images of rustic game dishes, wild forests, and traditional hunting practices. Yet, despite being almost exclusively associated with deer today, the word has a far broader and more complex history than most realize. Understanding why deer meat is called venison requires a journey through language, conquest, and culinary evolution spanning over a thousand years. This article explores the linguistic roots of “venison,” its transformation through medieval Europe, and how it became synonymous with deer meat in modern English.

The Latin Origins: From \"Venari\" to \"Venison\"

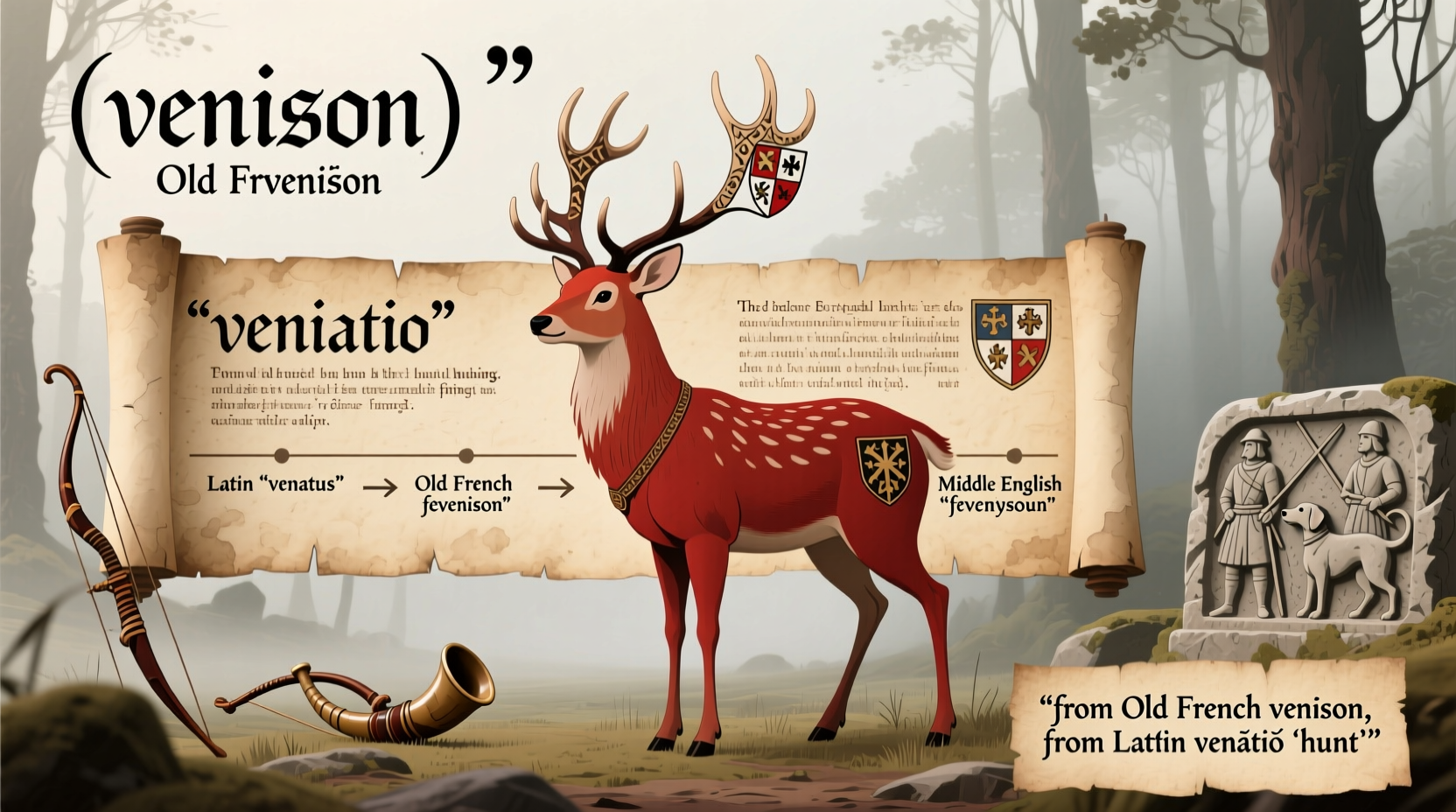

The story begins in ancient Rome. The Latin verb venari means “to hunt,” and from it came the noun venatio, referring to a hunt or hunting ground. The Romans used the term venison (in its Late Latin form venesonem) to describe the meat of any animal that had been hunted — not just deer, but also boar, hare, and even wild fowl. In this context, “venison” was not a species-specific label but a category defined by method: hunted game.

This broad usage carried into early French. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, Vulgar Latin evolved into Old French, where venesoun (later venaison) retained the same general meaning: the flesh of wild animals obtained through hunting. It wasn’t until the Norman Conquest of England in 1066 that this term would take on a new cultural and linguistic significance.

The Norman Influence: A Linguistic Divide in Medieval England

When William the Conqueror seized the English throne, he brought with him not only a new ruling class but also the Norman-French language. Over time, this created a striking linguistic divide between the Anglo-Saxon peasants and the French-speaking nobility — especially in matters of food.

A well-known pattern emerged: Anglo-Saxon words were used for live animals, while their French counterparts described the meat once served at the table. For example:

| Live Animal (Old English) | Meat (Norman French) | Modern Equivalent |

|---|---|---|

| Cū (cow) | Bœuf | Beef |

| Swīn (pig) | Porc | Pork |

| Deor (deer) | Veneson | Veal/Venison* |

| Fōgol (fowl/bird) | Volaille | Poultry |

*Note: While “veal” comes from “veau,” the young calf, “venison” remained tied to deer despite overlapping usage in earlier periods.

Deer were abundant in English forests and highly prized by the aristocracy for sport and sustenance. Because hunting rights were restricted to the nobility under forest law, the consumption of venison became a symbol of status. The common folk raised pigs and cattle, calling them “swine” and “cows,” but when these animals reached the noble table as food, they were renamed using French terms like “pork” and “beef.” Similarly, the deer (deor) roaming the royal forests became “venison” once prepared for feasting.

From General to Specific: How Venison Narrowed to Deer

In Middle English (circa 1100–1500), “venison” still referred broadly to game meat. However, as domesticated meats like beef, pork, and mutton dominated everyday diets, wild game became increasingly specialized. By the 16th century, “venison” had largely shed its broader meaning and become closely associated with deer — particularly red deer and fallow deer, which were the primary species hunted in England.

This narrowing coincided with changes in land use and hunting regulations. As royal forests were enclosed and game laws tightened, deer became the quintessential “noble beast,” and their meat the most prestigious form of venison. Other game meats began to be labeled more specifically — “hare,” “pheasant,” “boar” — leaving “venison” to stand almost exclusively for deer.

“Language reflects power. The fact that ‘venison’ survived as a culinary term while other game names faded speaks to the cultural dominance of deer hunting among European elites.” — Dr. Eleanor Hartwell, Historical Linguist, University of Oxford

Global Usage and Modern Misconceptions

Today, in North America, “venison” universally refers to meat from white-tailed deer, mule deer, elk, moose, and sometimes even antelope or caribou. However, regional differences persist. In parts of Europe, particularly France and Italy, the word for game meat remains broader. The French venaison still technically includes various wild ungulates, though in practice it most often means deer.

A common misconception is that “venison” is a modern euphemism or marketing term invented to make game sound more palatable. In reality, it’s one of the oldest food-related words in English, with roots stretching back to antiquity. Its survival is a testament to the enduring cultural importance of hunting and the aristocratic dining traditions that shaped the English language.

Interestingly, in some African and Caribbean countries, “venison” is occasionally misapplied to goat meat due to historical colonial terminology, though this usage is now considered incorrect in standard English.

Timeline: The Evolution of \"Venison\"

- c. 1st Century CE: Latin venari (“to hunt”) gives rise to venesonem, meaning hunted meat.

- c. 9th–11th Century: Old French venesoun enters use, denoting game meat of any kind.

- 1066: Norman Conquest introduces French culinary terms into England; “venison” becomes associated with elite hunting culture.

- 12th–14th Century: “Venison” appears frequently in legal documents and cookbooks, often specifying deer.

- 16th Century: Semantic narrowing completes; “venison” primarily denotes deer meat.

- 20th–21st Century: Term persists in hunting communities and gourmet cuisine, symbolizing sustainable, wild-sourced protein.

Practical Guide: Handling and Labeling Venison Today

For hunters, chefs, and consumers, understanding the correct use of “venison” matters for both accuracy and tradition. Here’s a checklist to ensure proper handling and communication:

- Use “venison” specifically for meat from deer species (e.g., whitetail, red deer, elk).

- Label products clearly to avoid confusion — especially in regions where unfamiliarity with game meats may lead to misunderstandings.

- Educate customers or diners about the origin and heritage of venison to enhance appreciation.

- Avoid using “venison” for non-cervid game like rabbit or wild boar; instead, use precise terms.

- Store venison properly: vacuum-seal and freeze if not consumed within 3–5 days to preserve quality.

FAQ: Common Questions About Venison

Is venison only from deer?

Yes, in modern usage, “venison” refers specifically to the meat of deer and closely related cervids like elk, moose, and reindeer. While historically it meant any hunted game, contemporary standards reserve it for deer-family animals.

Why don’t we call it “deer meat” instead of venison?

The persistence of “venison” is a direct result of the Norman linguistic legacy in English. Just as “beef” sounds more refined than “cow meat,” “venison” carries connotations of tradition, sophistication, and wild origin that “deer meat” lacks.

Can you eat venison rare?

Yes, high-quality, properly handled venison can be safely consumed medium-rare to enhance tenderness and flavor. However, it must be sourced from healthy animals and processed under sanitary conditions to minimize risk.

Conclusion: A Word Rooted in History and Tradition

The word “venison” is far more than a fancy synonym for deer meat. It is a linguistic artifact of conquest, class, and culinary tradition, tracing a path from Roman hunting grounds to medieval banquets and modern wilderness tables. Its endurance in the English language reflects not just a preference for certain meats, but a deep cultural narrative about who hunted, who dined, and how language evolves under social pressure.

Whether you’re a hunter, chef, historian, or curious food lover, recognizing the etymology and history behind “venison” enriches your understanding of food culture. Next time you savor a dish of venison, remember: you're tasting not just wild game, but a millennium of history.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?