Deflation—the sustained drop in general price levels across an economy—is often mistaken as a benefit to consumers. After all, lower prices mean more purchasing power, right? While that may seem true in the short term, persistent deflation can trigger a cascade of damaging economic consequences. Unlike temporary price dips, chronic deflation undermines growth, discourages investment, and deepens financial hardship for both individuals and governments. Understanding why deflation is dangerous is essential for grasping broader macroeconomic stability.

The Mechanics of Deflation: More Than Just Lower Prices

At its core, deflation occurs when the inflation rate falls below zero, meaning goods and services cost less over time. This can stem from several causes: weakened consumer demand, technological advancements that reduce production costs, or tight monetary policy that restricts the money supply. While moderate productivity-driven price declines (like in electronics) are not inherently harmful, broad-based deflation tied to weak demand signals deeper structural problems.

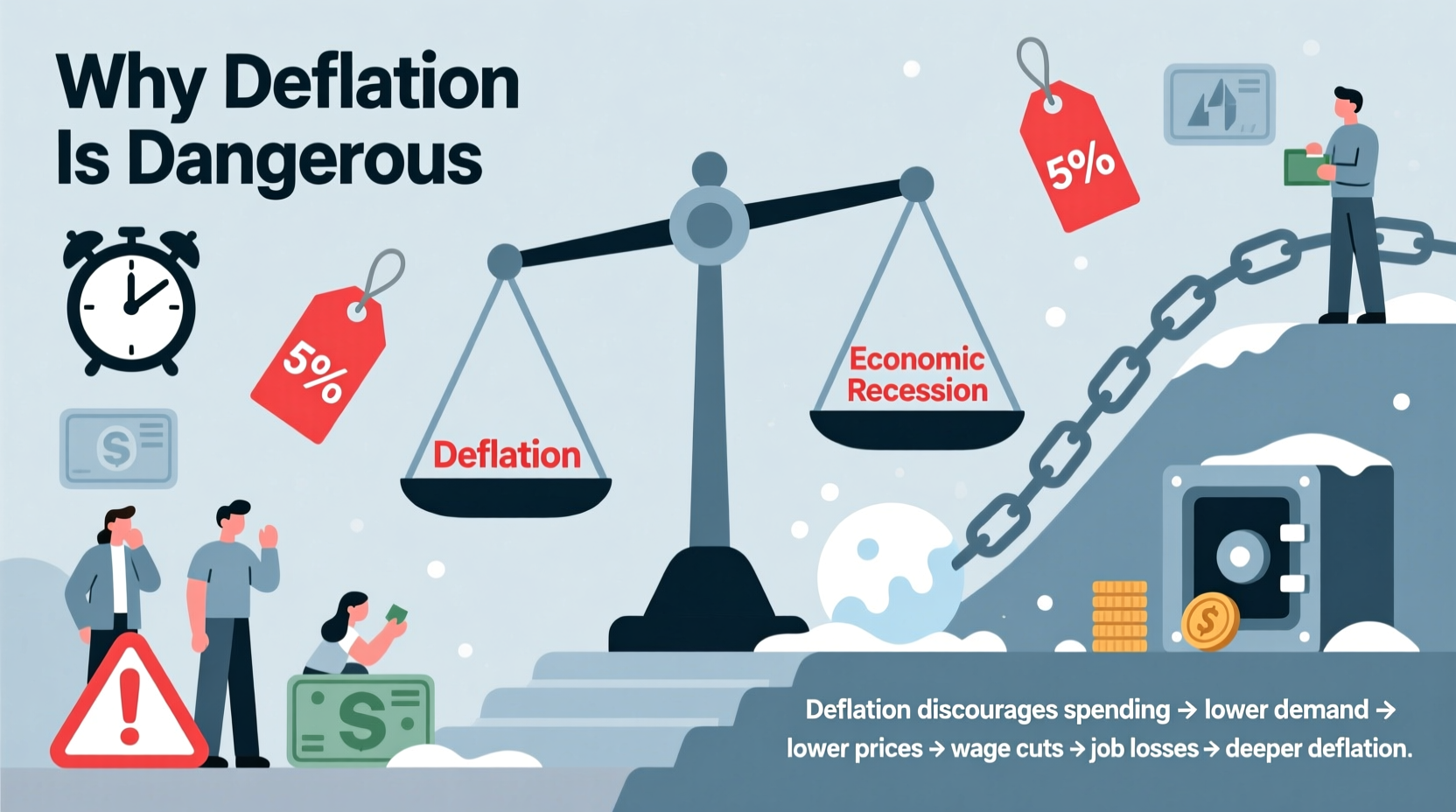

When people expect prices to keep falling, they delay purchases. Why buy a car today if it might be cheaper next month? This hesitation reduces aggregate demand, leading businesses to cut production, lay off workers, and further lower prices—creating a self-reinforcing cycle. As revenue drops, companies struggle to service debts, wages stagnate, and unemployment rises.

“Once deflation takes hold, it becomes extremely difficult to escape. Expectations become entrenched, and monetary policy loses traction.” — Ben Bernanke, Former Chair of the Federal Reserve

How Deflation Harms Consumers and Businesses

On the surface, lower prices appear beneficial. But the real cost emerges in income and employment. As demand slows, businesses earn less. To maintain profitability, they reduce staff or freeze hiring. Workers face wage cuts or job loss, which further suppresses spending. This feedback loop—lower spending → lower output → higher unemployment → even lower spending—is known as a deflationary spiral.

For businesses, deflation increases the real value of debt. If a company borrowed $1 million last year, that same debt becomes harder to repay when revenues shrink due to falling prices. Even if nominal payments stay the same, the burden grows because each dollar earned is worth more in real terms. This often leads to defaults, bankruptcies, and credit contraction.

The Debt Deflation Trap

Economist Irving Fisher first described the “debt-deflation theory” during the Great Depression. When asset prices fall—such as homes or stocks—borrowers find themselves underwater on loans. Simultaneously, the real value of their debt increases. This forces households and firms to sell assets or cut spending to pay down debt, further depressing prices and economic activity.

Consider a homeowner who owes $300,000 on a house now valued at $250,000. With falling prices expected, they may stop spending on nonessentials to protect against future losses. Multiply this behavior across millions of households, and you have a significant drag on GDP.

Governments are not immune. In a deflationary environment, tax revenues decline while social spending (e.g., unemployment benefits) rises. This worsens budget deficits. Yet raising taxes or cutting spending to balance budgets only deepens the downturn—a painful lesson learned by Japan and parts of Europe post-2008.

Case Study: Japan’s Lost Decade

Japan offers the most prominent modern example of deflation’s long-term damage. Starting in the early 1990s after a massive asset bubble burst, the country entered a prolonged period of stagnant growth and falling prices. Despite near-zero interest rates and repeated fiscal stimulus, consumer confidence remained weak.

Japanese consumers, expecting prices to drop, delayed major purchases. Companies responded by freezing wages and avoiding capital investment. The Bank of Japan struggled to generate inflation, resorting to quantitative easing years before other central banks. Even today, decades later, Japan battles low growth and periodic deflation.

The lesson: once deflation takes root in public expectations, reversing it requires extraordinary policy measures—and even then, success is uncertain.

Monetary Policy Limitations During Deflation

Central banks typically fight recessions by lowering interest rates to encourage borrowing and spending. But when deflation hits, this tool becomes ineffective. Nominal interest rates cannot fall below zero (or only slightly, in rare cases), creating the “zero lower bound” problem.

If prices are falling at 2% per year, even a 0% interest rate means real borrowing costs are +2%. That’s still too high to stimulate demand. At this point, conventional monetary policy loses its punch, forcing reliance on unconventional tools like asset purchases or forward guidance—tools with uncertain effectiveness and potential side effects.

Deflation vs. Disinflation: Know the Difference

| Term | Definition | Economic Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Deflation | Sustained decrease in general price levels | High risk: reduces spending, increases debt burden, triggers recession |

| Disinflation | Slowing of inflation (prices still rise, but more slowly) | Moderate concern: may signal weakening demand, but not inherently dangerous |

| Hyperinflation | Extremely rapid price increases | Destabilizing: erodes savings, disrupts markets |

Disinflation is not the same as deflation. A slowdown in inflation—from 5% to 2%, for example—can be managed. True deflation, where prices actually fall, poses far greater risks.

Strategies to Combat Deflation: A Policy Checklist

Preventing or reversing deflation requires coordinated action. Here’s what economists and policymakers recommend:

- Aggressive monetary easing: Cut interest rates early and use quantitative easing to inject liquidity.

- Fiscal stimulus: Increase government spending on infrastructure, education, or direct transfers to boost demand.

- Manage expectations: Central banks should clearly communicate inflation targets to anchor public sentiment.

- Debt relief programs: For households and businesses, temporary forbearance can prevent fire sales and defaults.

- Structural reforms: Improve labor mobility, innovation incentives, and competition to support long-term growth.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is deflation always bad?

Not always. Short-term, supply-driven price declines—like cheaper solar panels due to improved technology—are beneficial and not harmful. The danger lies in persistent, demand-driven deflation that signals weak economic activity and alters consumer and investor behavior.

Can individuals protect themselves from deflation?

Yes. Holding fixed-income assets like government bonds becomes more valuable during deflation, as the real return increases. Paying down high-interest debt also makes sense, since wages may stagnate. However, avoiding all spending can collectively worsen the downturn—a paradox known as the “paradox of thrift.”

Has the U.S. ever experienced deflation?

Yes. The U.S. faced severe deflation during the Great Depression (1929–1933), when prices fell over 10% annually at their worst. More recently, there were brief periods of deflation in 2009 and 2020 due to demand shocks from financial and health crises, but aggressive policy responses prevented long-term entrenchment.

Conclusion: Vigilance Against the Silent Threat

Deflation may sound appealing in isolation—a world of cheaper groceries, fuel, and rent. But its broader impact reveals a darker reality: shrinking incomes, rising debt pressure, and stalled economies. Once expectations shift toward falling prices, reversing the trend becomes exponentially harder.

Policymakers must act swiftly at the first signs of deflationary pressure. For citizens, understanding these dynamics helps make informed financial decisions and supports responsible public discourse on economic policy. Economic health depends not just on price levels, but on confidence, circulation, and growth.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?