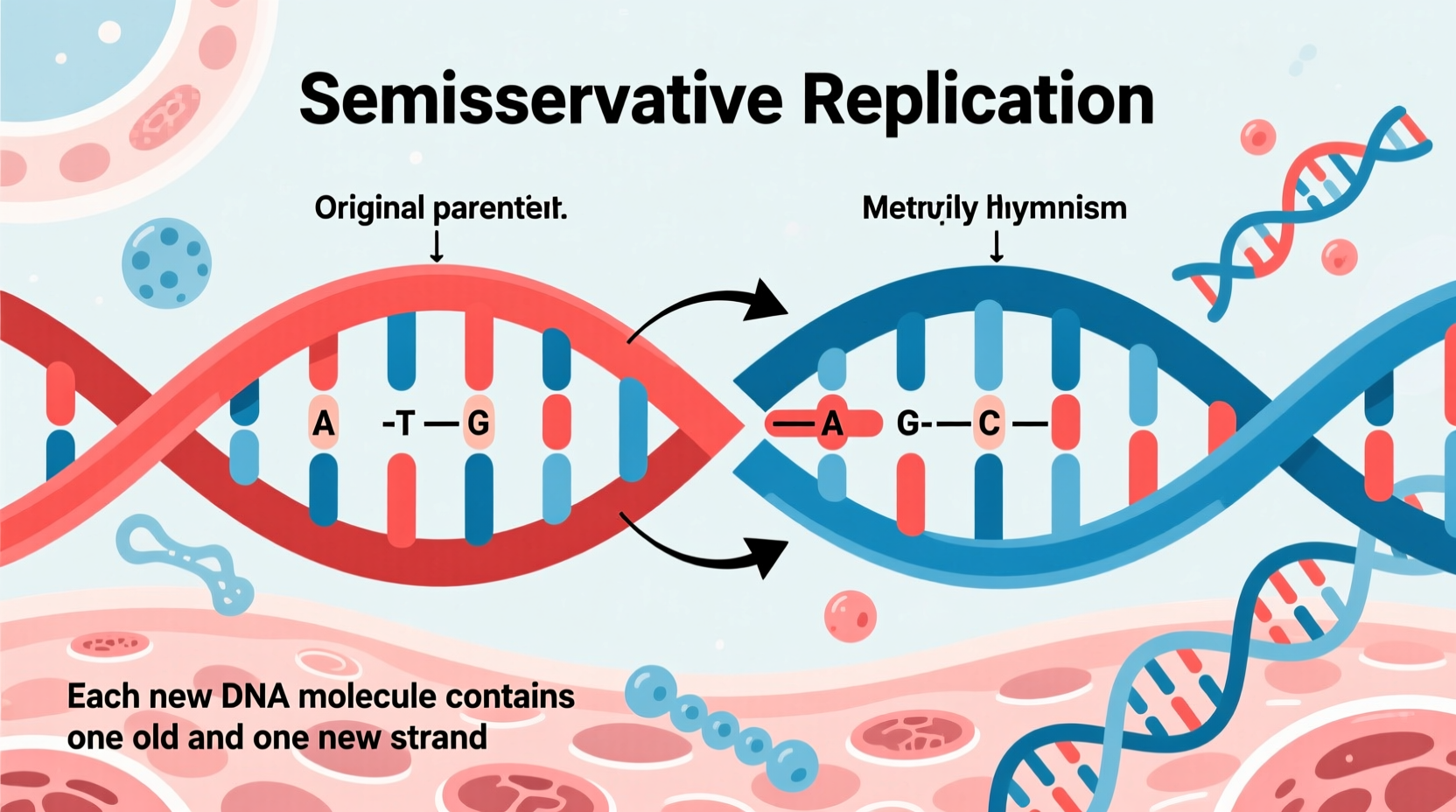

DNA replication is one of the most fundamental processes in biology, ensuring that genetic information is accurately passed from one generation of cells to the next. At the heart of this precision lies a key characteristic: semiconservative replication. This means that when a double helix of DNA duplicates, each of the two new DNA molecules consists of one original (parental) strand and one newly synthesized strand. This mechanism is not just a biological curiosity—it’s essential for maintaining genetic stability across generations of cells and organisms.

The concept of semiconservative replication was once a subject of scientific debate. In the 1950s, after Watson and Crick discovered the double-helix structure of DNA, three models were proposed for how replication might occur: conservative, dispersive, and semiconservative. It wasn’t until the elegant Meselson-Stahl experiment in the late 1950s that the semiconservative model was definitively proven. Understanding why this method evolved—and why it matters—reveals deep insights into cellular function and genetic fidelity.

The Three Proposed Models of DNA Replication

Before the mechanism was confirmed, scientists speculated on how DNA might replicate. The three main hypotheses were:

- Conservative replication: The original double helix remains intact, and a completely new double-stranded molecule is synthesized.

- Dispersive replication: Both strands of the new DNA molecules are mixtures of old and new DNA segments interspersed along each strand.

- Semiconservative replication: Each of the two new DNA molecules has one original strand and one newly formed strand.

While all three models were theoretically possible, only semiconservative replication aligned with both structural evidence and experimental data.

The Meselson-Stahl Experiment: Proving Semiconservative Replication

In 1958, Matthew Meselson and Franklin Stahl conducted a landmark experiment using isotopes of nitrogen to distinguish between old and new DNA strands. They grew E. coli bacteria in a medium containing heavy nitrogen (¹⁵N) for several generations, causing the DNA to become \"heavy.\" Then, they transferred the bacteria to a medium with light nitrogen (¹⁴N). After each generation, they extracted DNA and analyzed its density using centrifugation.

The results were clear:

- Generation 0: All DNA was heavy (¹⁵N/¹⁵N).

- First generation: All DNA had an intermediate density (¹⁵N/¹⁴N), ruling out conservative replication (which would have produced one heavy and one light band).

- Second generation: Two bands appeared—one intermediate (¹⁵N/¹⁴N) and one light (¹⁴N/¹⁴N)—exactly matching predictions for semiconservative replication.

This experiment provided definitive proof: DNA replication is semiconservative. No other model could explain the observed pattern of DNA densities across generations.

Why Evolution Favored Semiconservative Replication

Nature selected semiconservative replication for compelling functional reasons. This method balances efficiency, accuracy, and error correction—critical for sustaining life.

One major advantage is the preservation of one original template strand. This strand serves as a reference during replication, allowing repair enzymes to identify and correct mistakes in the new strand. If both strands were newly synthesized (as in a hypothetical conservative model), there would be no template to compare against, increasing mutation risk.

Additionally, semiconservative replication supports the antiparallel nature of DNA. Because DNA polymerase can only add nucleotides in the 5' to 3' direction, the leading and lagging strands are synthesized differently. Yet, having one conserved strand ensures that both copies maintain sequence fidelity despite this asymmetry.

“Semiconservative replication is nature’s way of ensuring that every cell inherits a verified copy of the genome—with built-in redundancy for error checking.” — Dr. Helen Reyes, Molecular Biologist

Step-by-Step Process of Semiconservative DNA Replication

DNA replication unfolds in a tightly regulated sequence. Here's how semiconservation is achieved at the molecular level:

- Initiation: Proteins bind to the origin of replication, unwinding the double helix and forming a replication bubble. Helicase breaks hydrogen bonds between base pairs, creating two single strands.

- Primer Binding: Primase synthesizes a short RNA primer on each template strand, providing a starting point for DNA polymerase.

- Elongation: DNA polymerase adds complementary nucleotides to each template. One strand (leading) is synthesized continuously; the other (lagging) in fragments called Okazaki fragments.

- Proofreading: DNA polymerase checks each added nucleotide and corrects mismatches using exonuclease activity.

- Ligation: DNA ligase joins Okazaki fragments on the lagging strand, sealing the sugar-phosphate backbone.

- Termination: Replication ends when forks meet or reach chromosome ends. Each resulting DNA molecule contains one old and one new strand.

This entire process occurs with remarkable speed and accuracy—up to 1,000 nucleotides per second in bacteria, with fewer than one error per billion bases.

Comparison of Replication Models

| Model | Strand Composition After Replication | Supported by Evidence? | Key Weakness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | One molecule with both original strands; one with both new strands | No | Fails Meselson-Stahl test; no template available for repair in new molecule |

| Dispersive | Both molecules contain mixed segments of old and new DNA | No | Would fragment genetic continuity; inconsistent with density gradient results |

| Semiconservative | Each molecule has one old and one new strand | Yes | None—biologically optimal for fidelity and repair |

Real-World Implications: A Case Study in Genetic Stability

Consider the case of rapidly dividing cells in human bone marrow. These hematopoietic stem cells undergo frequent DNA replication to produce blood cells. If replication were not semiconservative, errors could accumulate rapidly, leading to dysfunctional proteins or cancerous mutations.

In patients with certain DNA repair deficiencies, such as those with Lynch syndrome, even minor lapses in replication fidelity increase cancer risk. This underscores the importance of having one conserved strand as a reference during synthesis. The semiconservative method, combined with mismatch repair systems, acts as a dual safeguard—ensuring that most errors are caught before becoming permanent mutations.

Common Misconceptions About Semiconservative Replication

Despite being well-established, some misunderstandings persist:

- Misconception: Semiconservative means half the DNA is saved. Reality: It refers to the physical retention of one complete strand per duplex, not a percentage of nucleotides.

- Misconception: The process is perfectly error-free. Reality: While highly accurate, errors do occur—about 1 in 100 million bases—but are corrected by proofreading and repair pathways.

- Misconception: All organisms replicate DNA the same way. Reality: While the semiconservative principle is universal, details vary—e.g., circular vs. linear chromosomes, number of origins.

FAQ: Frequently Asked Questions

Why can't DNA replication be conservative?

If replication were conservative, one daughter cell would receive the original double helix while the other gets a brand-new copy. This would deprive the new molecule of a template for error correction, drastically increasing mutation rates and compromising genetic integrity.

Is semiconservative replication universal?

Yes. From bacteria to humans, all known cellular life forms use semiconservative DNA replication. This universality highlights its evolutionary advantage in preserving genetic information.

What happens if the old strand gets damaged?

If the parental strand is damaged, repair mechanisms like nucleotide excision repair act before or after replication. Cells prioritize repairing the template strand because it guides accurate synthesis of the new strand.

Conclusion: The Foundation of Genetic Continuity

Semiconservative DNA replication is more than a textbook fact—it’s a cornerstone of life. By preserving one original strand in each new DNA molecule, cells ensure that genetic information is copied with extraordinary fidelity. This mechanism enables growth, repair, and inheritance, linking every living organism through a shared molecular legacy.

Understanding why DNA replication is semiconservative reveals the elegance of biological design: a balance of innovation and conservation, where the past guides the future. As research continues into DNA repair, aging, and disease, this foundational principle remains central to advancing medicine and biotechnology.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?