Dry ice—solid carbon dioxide—is a powerful cooling agent widely used in food preservation, medical transport, and industrial applications. While it’s effective at keeping items frozen far longer than regular ice, its extreme cold and unique chemical properties make it inherently hazardous if mishandled. From frostbite to asphyxiation, the dangers of dry ice are real and sometimes underestimated. Understanding these risks and adopting strict safety measures is essential for anyone using or transporting it.

The Science Behind Dry Ice and Its Hazards

Dry ice exists at a temperature of -109.3°F (-78.5°C), which is significantly colder than standard freezer temperatures. Unlike water ice, it doesn’t melt into a liquid; instead, it sublimates directly from solid to gas, releasing carbon dioxide (CO₂) into the surrounding air. This process is efficient for cooling but introduces two primary dangers: extreme cold exposure and CO₂ buildup.

When dry ice sublimates in an enclosed space—such as a car trunk, small room, or poorly ventilated storage area—CO₂ can accumulate rapidly. Because CO₂ is heavier than air, it displaces oxygen near floor level, increasing the risk of suffocation without visible warning signs. In high concentrations, CO₂ can cause dizziness, headaches, increased heart rate, and even loss of consciousness.

“Dry ice is not just ‘extra-cold ice.’ It presents both thermal and atmospheric hazards that require serious precautions.” — Dr. Alan Reyes, Industrial Safety Consultant

Common Risks of Improper Dry Ice Handling

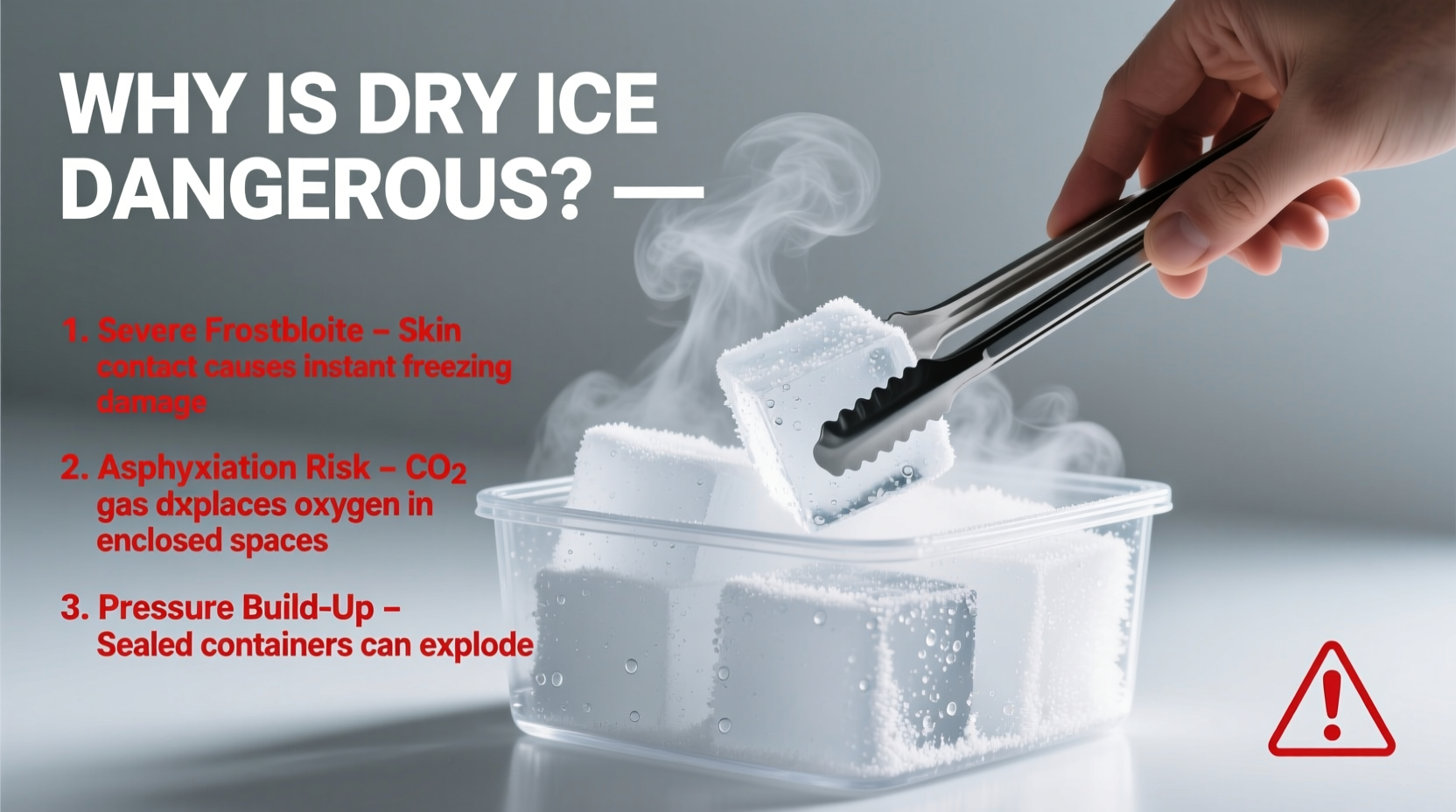

The most frequent injuries associated with dry ice stem from direct contact, improper storage, and inadequate ventilation. Below are the most common risks:

- Frostbite and skin damage: Touching dry ice without protection causes instant freeze burns similar to thermal burns.

- Respiratory distress: Inhaling high levels of CO₂ in confined areas can lead to hypoxia (oxygen deficiency).

- Explosions from pressure buildup: Sealing dry ice in airtight containers leads to rapid gas expansion and potential rupture.

- Ingestion hazards: Consuming dry ice, even accidentally in drinks, can cause internal burns or gas expansion in the digestive tract.

- Slippery surfaces: As dry ice sublimates on floors, it can create fog and slick conditions, especially in refrigerated environments.

Safety Checklist for Using Dry Ice

To minimize danger, follow this actionable checklist every time you work with dry ice:

- Wear insulated gloves and eye protection during handling.

- Use only in well-ventilated areas—avoid basements, closets, or sealed vehicles.

- Store in an insulated cooler, never in airtight containers like glass jars or plastic Tupperware.

- Label containers clearly: “Dry Ice – Do Not Seal.”

- Keep away from children and pets.

- Limit storage time—most coolers only safely hold dry ice for 18–24 hours.

- Never store dry ice in a home refrigerator or freezer—CO₂ buildup can damage appliances and pose inhalation risks.

- Dispose of unused dry ice outdoors, allowing it to sublimate safely in open air.

Storage Do’s and Don’ts

| Do’s | Don’ts |

|---|---|

| Store in an insulated cooler with the lid slightly ajar for ventilation. | Seal dry ice in airtight containers (e.g., thermos, vacuum flask, or plastic container). |

| Place the cooler in a well-ventilated area like a garage or outdoor porch. | Keep dry ice in occupied rooms, bedrooms, or vehicles where people are present. |

| Use Styrofoam coolers designed for dry ice shipment. | Store dry ice in freezers—CO₂ can damage thermostat sensors and seals. |

| Allow space for gas to escape—do not overpack. | Leave dry ice unattended in public spaces or unmarked containers. |

Real-World Incident: A Cautionary Example

In 2021, a family in Ohio transported several blocks of dry ice in the trunk of their sedan to bring frozen meals home from a medical facility. After about 30 minutes of driving, the driver began feeling dizzy and disoriented. The passenger experienced shortness of breath. They pulled over just in time. Emergency responders discovered elevated CO₂ levels inside the vehicle, particularly in the rear cabin. The trunk had no venting, and sublimating dry ice had filled the connected space with invisible gas.

No one was seriously injured, but the incident highlighted a common misconception: that short trips are safe. Even brief exposure in enclosed spaces can be dangerous. The family later reported they didn’t know dry ice could pose an inhalation risk—they thought it was just “cold ice.”

Step-by-Step Guide to Safe Dry Ice Use

Follow this sequence to ensure maximum safety when using dry ice at home or work:

- Plan ahead: Purchase dry ice as close as possible to the time of use—typically within 24 hours.

- Prepare protective gear: Gather insulated gloves, goggles, and tongs before opening the package.

- Open carefully: Unwrap dry ice outdoors or in a ventilated area to avoid sudden CO₂ release.

- Use appropriate containers: Place in a polystyrene cooler with the lid loosely closed or punctured for airflow.

- Monitor sublimation: Check periodically—dry ice typically loses 5–10% of mass per day, depending on insulation.

- Dispose properly: Leave remaining pieces in a well-ventilated outdoor area—never down sinks or in trash cans indoors.

- Clean up after: Wipe down any surface that came into contact with dry ice, as residual cold can damage materials.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can dry ice explode in a car?

Yes. If dry ice is stored in a sealed trunk or cabin, CO₂ buildup can increase pressure and potentially damage the vehicle’s structure or lead to asphyxiation. Never leave dry ice in a parked car, and always crack a window if transporting it.

Is it safe to use dry ice in drinks?

Only if used correctly. Small, food-grade pellets labeled “for culinary use” can create dramatic fog effects, but they must never be consumed. The ice must fully sublimate before drinking, and glasses should be monitored closely. Never serve dry ice in punch bowls accessible to guests without supervision.

How long does dry ice last in a cooler?

Depending on the cooler quality and ambient temperature, dry ice lasts 18 to 24 hours in a standard 25-quart cooler. When stored in a well-insulated Styrofoam container, it may last up to 36 hours. Avoid opening the cooler frequently, as each exposure accelerates sublimation.

Final Thoughts: Respect the Cold

Dry ice is a valuable tool, but it demands respect and caution. Its ability to preserve vaccines, freeze gourmet desserts, or create theatrical effects makes it indispensable in many fields. Yet, treating it casually—like ordinary ice—can have severe consequences. By understanding the science behind its dangers and following clear safety protocols, users can harness its power without compromising health or safety.

Whether you're a caterer, scientist, or homeowner preparing for a power outage, your awareness today could prevent an emergency tomorrow. Knowledge isn't just protective—it's empowering.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?