The global appetite for trendy, affordable clothing has fueled the rise of fast fashion—a business model built on speed, low cost, and high turnover. While consumers enjoy new styles every few weeks, the environmental toll is immense. Among the most critical yet under-discussed impacts is its effect on water resources. Fast fashion consumes staggering amounts of freshwater and contaminates vast quantities through chemical-laden wastewater. Behind every cheap t-shirt or polyester dress lies a hidden water footprint that stretches across continents, affecting ecosystems, communities, and future generations.

This article examines how fast fashion’s relentless production cycle drives excessive water use—from cotton farming to fabric dyeing—and explores the long-term consequences for both people and the planet. By understanding the depth of this crisis, we can make more informed choices and push for systemic change in the industry.

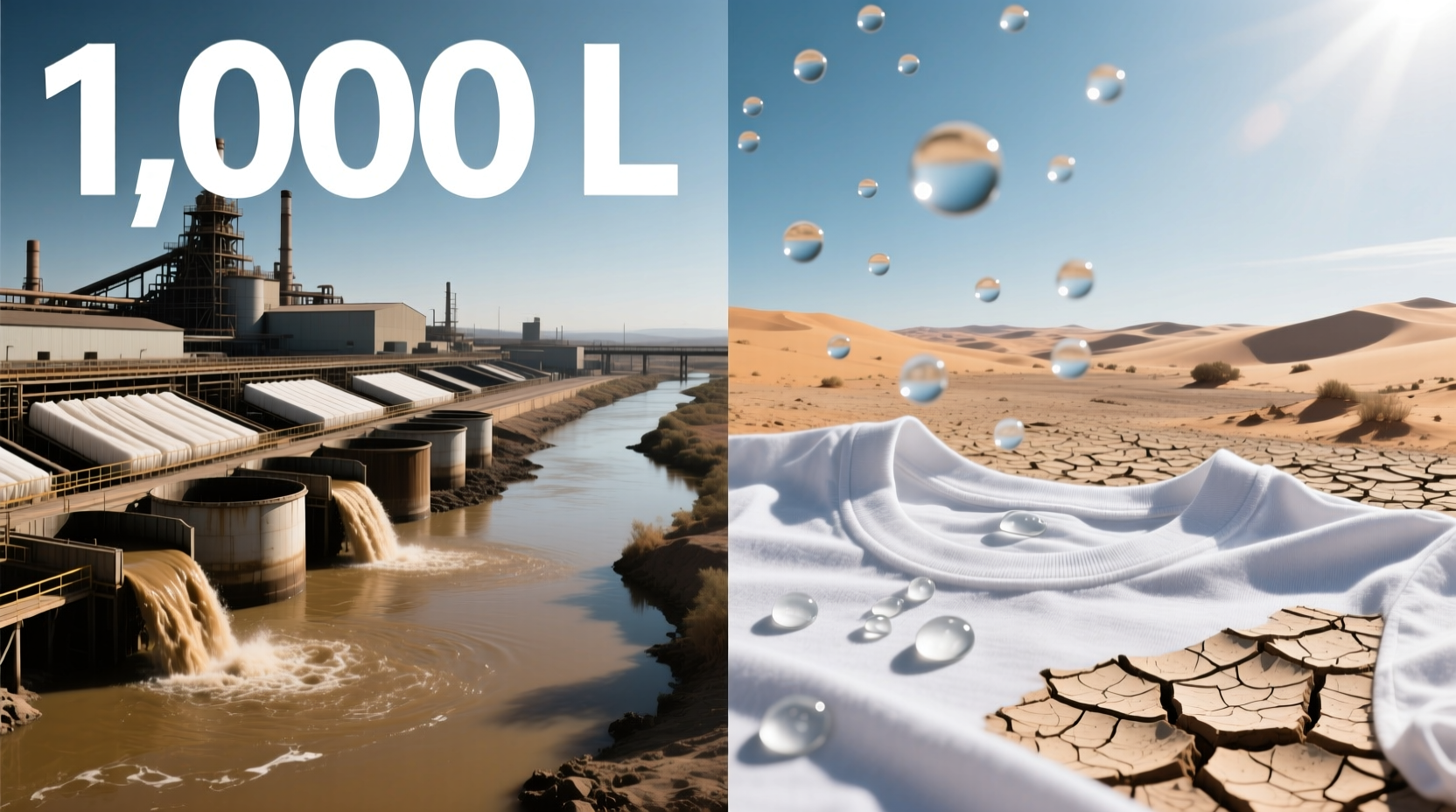

The Hidden Water Footprint of a Single Garment

Every piece of clothing begins with raw materials, many of which are extremely water-intensive to grow or produce. Take cotton, one of the most widely used natural fibers in fast fashion. Although it accounts for only about 2.5% of global crop land, cotton cultivation consumes nearly 3% of all freshwater used in agriculture. Producing just one kilogram of raw cotton requires between 10,000 and 20,000 liters of water—equivalent to filling a small backyard swimming pool.

A single cotton t-shirt may require up to 2,700 liters of water to produce—enough to meet one person’s drinking needs for 900 days. When multiplied by the estimated 2 billion t-shirts sold globally each year, the scale becomes incomprehensible: over 5 trillion liters of water annually, much of it drawn from already stressed watersheds.

Synthetic fibers like polyester, while not grown in fields, also contribute to water stress indirectly. Their production relies heavily on fossil fuels, and the refining and processing of petroleum-based feedstocks demand large volumes of cooling and process water. Moreover, microplastic pollution from washing synthetic garments introduces another layer of aquatic contamination.

“Water scarcity is no longer a regional issue—it's a supply chain emergency. The fashion industry must confront its role as one of the largest industrial water users.” — Dr. Anita Roy, Environmental Scientist, Water Resources Institute

Water Depletion in Vulnerable Regions

Fast fashion’s thirst for water disproportionately affects regions already facing water scarcity. Many garment-producing countries, such as Bangladesh, India, Vietnam, and China, rely on major river systems like the Indus, Ganges, and Mekong. These rivers support millions of farmers, fishermen, and families—but they are increasingly overdrawn due to industrial and agricultural demands.

In Uzbekistan, the Aral Sea disaster stands as one of the starkest examples of water mismanagement driven by textile production. Once the fourth-largest lake in the world, it has shrunk to less than 10% of its original size after Soviet-era irrigation projects diverted rivers to grow cotton. Today, former seabeds are barren deserts laced with salt and pesticides, rendering the land unusable and causing severe respiratory illnesses among nearby populations.

Even where lakes haven’t vanished, groundwater tables are collapsing. In parts of Gujarat, India, cotton farmers have drilled wells over 600 feet deep to access dwindling aquifers. As water becomes scarcer, competition intensifies between industries, agriculture, and households, often leaving marginalized communities without reliable access to clean water.

Pollution from Dyeing and Finishing Processes

While water consumption is alarming, the pollution generated during textile manufacturing may be even more damaging. Dyeing and finishing account for nearly 20% of global industrial water pollution, according to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). In countries with weak environmental regulations, untreated wastewater from textile factories is routinely discharged directly into rivers and streams.

In Xintang, China—once known as the “jeans capital of the world”—local rivers turned indigo blue from denim runoff. Chromium, cadmium, and other heavy metals used in dyes and treatments seeped into the soil and water table, poisoning fish and making farmland unusable. Similar scenes play out in Tirupur, India, where effluent from hundreds of dye houses once rendered the Noyyal River biologically dead.

The problem isn’t limited to visible discoloration. Toxic chemicals in textile wastewater include formaldehyde, chlorine bleaches, flame retardants, and perfluorinated compounds (PFCs), many of which are carcinogenic or endocrine disruptors. These substances persist in the environment, accumulate in food chains, and pose serious health risks to factory workers and downstream communities.

| Textile Process | Water Used (liters/kg fabric) | Common Pollutants |

|---|---|---|

| Cotton cultivation | 8,000–20,000 | Pesticides, fertilizers |

| Fabric dyeing | 100–150 | Heavy metals, synthetic dyes |

| Finishing treatments | 50–100 | Formaldehyde, PFCs |

| Washing (industrial) | 60–80 | Microfibers, detergents |

Case Study: The True Cost of Denim in Bangladesh

Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh, hosts thousands of garment factories producing jeans for Western retailers. A 2021 investigation by the Changing Markets Foundation revealed that clusters of denim processors in Savar and Gazipur were releasing up to 12 million liters of untreated wastewater daily into the Buriganga River. This river, which supplies water to over 20 million people, now contains lead levels 17 times above safe limits and chromium concentrations exceeding WHO guidelines by a factor of five.

Local residents report skin rashes, gastrointestinal issues, and declining fish catches. Farmers downstream find their crops stunted and soils contaminated. Despite existing environmental laws, enforcement remains weak, and economic pressure to meet export quotas often overrides ecological concerns.

One factory worker, Fatima Akter, shared her experience: “We work near vats filled with colored water, but there’s no ventilation or protective gear. After shifts, my hands itch and crack. I worry about what this is doing to my body.” Her story reflects a broader pattern: human health sacrificed at every stage of the supply chain, from field to factory.

Consumer Habits and the Water Waste Cycle

Fast fashion thrives on short product lifespans. Consumers buy more clothes than ever before—up to 60% more than two decades ago—yet keep each item for half as long. This throwaway culture amplifies water waste in several ways:

- Increased production volume: More garments mean more raw materials, more dyeing, and more water consumed per capita.

- Higher washing frequency: Synthetic fabrics like polyester require frequent laundering due to odor retention, contributing to household water use and microfiber shedding.

- Shorter garment life: Poor-quality stitching and materials lead to early disposal, negating any potential for water savings through reuse or longevity.

A study by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation found that extending the average life of clothing by just nine months could reduce water consumption per item by 20–30%. Yet fast fashion incentivizes rapid turnover, discouraging care, repair, and mindful ownership.

Checklist: Reduce Your Fashion Water Footprint

- Buy fewer, higher-quality garments made from sustainable fibers.

- Choose organic cotton, hemp, or TENCEL™, which use less water and fewer chemicals.

- Wash clothes less often and in cold water to save energy and reduce microfiber release.

- Use a microfiber-catching laundry bag or filter.

- Support brands committed to water stewardship and transparency.

- Repair, alter, or donate clothes instead of discarding them.

- Advocate for stronger regulations on industrial water use and pollution control.

What Can Be Done? Industry Shifts and Policy Solutions

Addressing fast fashion’s water crisis requires systemic transformation. Some progress is being made. Brands like Levi’s have introduced Water®Less finishing techniques, reducing water use in denim production by up to 96%. Innovations such as air dyeing, which uses pressurized carbon dioxide instead of water, show promise for slashing industrial demand.

However, these efforts remain isolated. For real impact, three key changes are needed:

- Mandatory environmental reporting: Governments should require fashion companies to disclose water usage and pollution metrics across their supply chains.

- Stricter wastewater standards: Enforce zero-discharge policies for hazardous chemicals and invest in centralized treatment facilities in industrial zones.

- Incentivize circular models: Tax breaks or subsidies for brands using recycled fibers, offering take-back programs, or designing for durability.

Certifications like the Global Organic Textile Standard (GOTS) and the Higg Index help identify responsible producers, but consumer awareness and regulatory backing are essential to scale their influence.

Frequently Asked Questions

How much water does the fashion industry use annually?

The fashion industry consumes approximately 79 billion cubic meters of freshwater each year—equivalent to 32 million Olympic-sized swimming pools. This includes everything from fiber cultivation to garment manufacturing and consumer care.

Is synthetic fabric better for water conservation than cotton?

Not necessarily. While polyester doesn’t require irrigation, its production is energy-intensive and contributes to water pollution through microplastics. Additionally, fossil fuel extraction for synthetics often involves hydraulic fracturing, which consumes and contaminates large volumes of water.

Can individual actions really make a difference?

Yes. If every consumer extended the life of their clothes by nine months, global clothing-related water consumption would drop by an estimated 10%. Combined with advocacy and support for ethical brands, personal choices can drive market change.

Taking Action Beyond Awareness

Understanding the link between fast fashion and water consumption is only the first step. The next is action—on personal, community, and policy levels. Every time we choose quality over quantity, repair over replace, or transparency over trendiness, we reject the unsustainable logic of disposable fashion.

Brands must be held accountable for their environmental footprints, and governments must enforce stricter regulations on water use and pollution. But consumers also wield power through their purchasing decisions and voices. Demand better. Wear less. Care more.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?