Ginger’s sharp bite is familiar to anyone who’s taken a bite of fresh root or sipped a strong ginger tea. Unlike chili peppers, which ignite heat through capsaicin, ginger delivers a different kind of fire—one that tingles, warms, and lingers. This spiciness isn’t random; it stems from a class of bioactive compounds known as gingerols, primarily 6-gingerol. Understanding why ginger is spicy means diving into plant chemistry, sensory biology, and even evolutionary science. Beyond flavor, this pungency plays a crucial role in ginger’s medicinal reputation and culinary versatility.

The Chemistry Behind Ginger’s Heat: Meet Gingerol

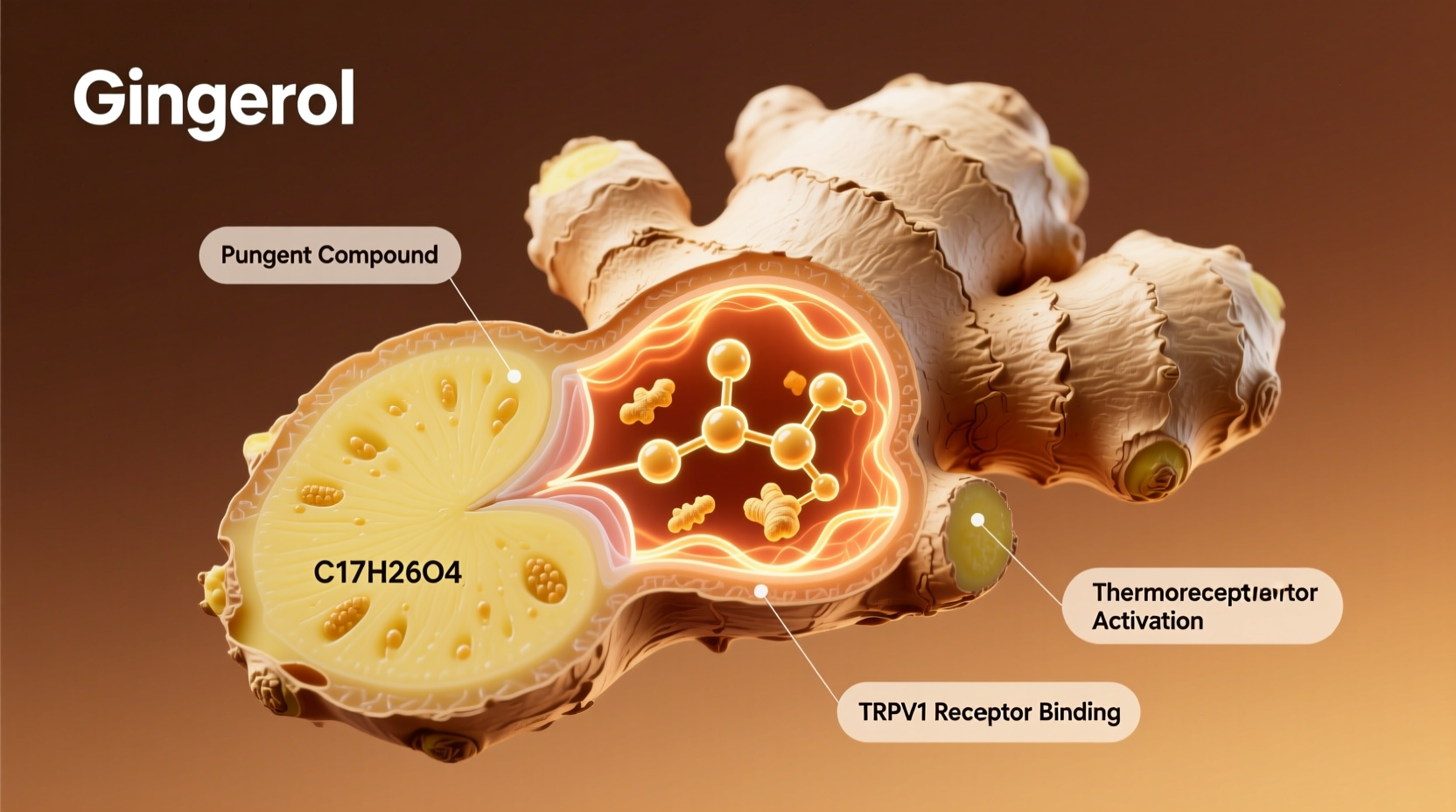

The primary compound responsible for ginger’s signature zing is 6-gingerol, a phenolic molecule found in high concentrations in fresh ginger root (Zingiber officinale). When you chew raw ginger, your mouth registers a warming, almost peppery sensation—this is gingerol activating sensory neurons in the oral cavity. Structurally, gingerol resembles vanillin and capsaicin, but its mechanism of action is distinct.

Gingerols belong to a family of compounds called alkylphenols. Their pungency arises from their ability to interact with transient receptor potential (TRP) channels—specifically TRPV1 and TRPA1—receptors associated with heat, pain, and chemical irritation. When gingerol binds to these receptors, it tricks the nervous system into perceiving warmth or mild burning, even though no actual temperature change occurs.

How Gingerol Changes with Heat and Storage

One fascinating aspect of gingerol is its instability under certain conditions. When ginger is heated, dried, or stored over time, 6-gingerol undergoes dehydration and transforms into other compounds:

- Shogaols: Formed when gingerol loses a water molecule during drying or cooking. Shogaols are significantly more pungent than gingerols—up to twice as potent—and are prevalent in dried ginger powder.

- Zingerone: Created when ginger is cooked slowly at lower temperatures. Zingerone is less spicy than gingerol and contributes to the sweet-spicy aroma of baked goods like gingerbread.

This transformation explains why dried ginger tastes sharper than fresh, while cooked ginger becomes milder and more aromatic. The balance between these compounds determines the final sensory profile of any ginger-containing dish.

Comparing Pungency: Ginger vs. Other Spicy Foods

Ginger’s heat doesn’t register on the Scoville scale, which measures capsaicin-based spiciness in chilies. Instead, scientists use relative pungency assays based on human sensory panels and chemical analysis. While not as intense as habaneros or ghost peppers, ginger delivers a unique type of irritation that builds gradually and spreads differently.

| Spicy Ingredient | Active Compound | Pungency Mechanism | Sensation Profile |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh Ginger | 6-Gingerol | Activates TRPV1 & TRPA1 | Warming, sharp, lingering |

| Chili Peppers | Capsaicin | Binds TRPV1 strongly | Burning, immediate, localized |

| Black Pepper | Piperine | Activates TRPV1 | Sharp, quick fade |

| Wasabi | Allyl isothiocyanate | Targets TRPA1 | Nasal burn, fleeting |

Unlike capsaicin, which tends to concentrate on the tongue, gingerol’s effect spreads across the mouth and throat, often accompanied by a pleasant warmth that can extend into the chest—a sensation many associate with comfort and digestion.

“Ginger’s pungency is more than just flavor—it’s a signal of bioactivity. The same compounds that make it spicy also contribute to its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects.” — Dr. Lena Patel, Phytochemistry Researcher, University of Cambridge

Biological Purpose: Why Does Ginger Produce Gingerol?

In nature, pungency often serves as a defense mechanism. For ginger, producing gingerol likely evolved to deter herbivores and protect against microbial pathogens. The compound exhibits antimicrobial properties, inhibiting the growth of bacteria and fungi in the rhizome’s environment.

Interestingly, humans are among the few mammals that not only tolerate but seek out pungent foods. Some researchers suggest that our attraction to spicy compounds may stem from an evolutionary advantage: many pungent plants, including ginger, possess medicinal qualities such as anti-nausea, anti-inflammatory, and circulatory benefits. By consuming slightly irritating substances, early humans may have gained protection against infections and digestive issues.

Culinary Implications of Ginger’s Pungency

Chefs and home cooks alike leverage ginger’s spiciness to add depth and complexity to dishes. Its heat cuts through rich, fatty flavors in curries and stir-fries, balances sweetness in desserts, and enhances umami in broths. Because gingerol’s potency changes with preparation, understanding how to manipulate it is key to mastering flavor profiles.

Step-by-Step Guide: Controlling Ginger’s Spiciness in Cooking

Whether you want to maximize or mellow ginger’s kick, follow these steps to control its pungency:

- Choose the right form: Fresh ginger contains mostly gingerol and offers a bright, clean heat. Use it raw in dressings or quick sautés for maximum zing.

- Dry or powder for intensity: Dried ginger has higher shogaol content, making it spicier. Ideal for spice blends or slow-cooked stews where deep warmth is desired.

- Cook gently to mellow flavor: Simmering ginger in liquid converts gingerol to zingerone, reducing sharpness and adding sweetness. Perfect for teas and syrups.

- Add late for punch: Stir fresh grated ginger into dishes in the last few minutes of cooking to preserve its volatile compounds and heat.

- Pair with fats or dairy: Fat molecules help dissolve and distribute pungent compounds evenly, softening the perceived intensity. Coconut milk in Thai curries does this effectively.

Health Benefits Linked to Gingerol’s Pungency

The very compounds that make ginger spicy are also responsible for many of its celebrated health effects. Studies show that 6-gingerol and its derivatives:

- Reduce inflammation by inhibiting COX-2 and other pro-inflammatory enzymes.

- Support digestion by stimulating saliva and gastric juices.

- Exhibit antioxidant activity, protecting cells from oxidative stress.

- May help alleviate nausea, especially in pregnancy and chemotherapy patients.

- Show promise in modulating blood sugar and supporting cardiovascular health.

However, these benefits are dose-dependent. Mild culinary use provides subtle support, while concentrated extracts (often standardized to gingerol content) are used in clinical settings. It’s worth noting that excessive consumption can lead to heartburn or gastrointestinal discomfort—proof that the line between stimulation and irritation is thin.

Mini Case Study: Using Ginger for Motion Sickness Relief

Sarah, a frequent traveler, struggled with motion sickness during long car rides. Over-the-counter medications left her drowsy, so she turned to natural remedies. After reading about ginger’s anti-nausea properties, she began taking 1 gram of powdered ginger in capsule form 30 minutes before travel. She also kept candied ginger on hand for snacking during trips.

Within two journeys, she noticed a dramatic reduction in nausea. The slight burn of the ginger seemed to “wake up” her stomach, preventing the queasy feeling that usually set in within minutes. Her experience aligns with multiple clinical trials showing ginger’s efficacy in reducing nausea without sedative side effects.

FAQ

Is ginger’s spiciness harmful?

No, for most people, ginger’s pungency is safe and even beneficial. However, those with sensitive stomachs or acid reflux may find large amounts irritating. Moderation is key.

Why does my mouth tingle after eating raw ginger?

The tingling is caused by 6-gingerol activating TRPA1 receptors in your oral mucosa. These nerves interpret the chemical signal as mild heat or vibration, creating the characteristic warm, prickly sensation.

Can I reduce ginger’s spiciness without losing flavor?

Yes. Pairing ginger with honey, citrus, or coconut milk can balance its heat while preserving its aromatic qualities. Cooking it slowly also converts harsh gingerols into smoother zingerone.

Conclusion

Ginger’s spiciness is far more than a culinary curiosity—it’s a sophisticated interplay of chemistry, biology, and evolution. From the molecular dance of gingerol binding to nerve receptors to its transformation under heat, every aspect of its pungency reveals a deeper story about how plants defend themselves and how humans have learned to harness those defenses for flavor and healing.

Understanding the science behind ginger’s bite empowers better cooking, smarter supplement choices, and greater appreciation for one of the world’s most versatile spices. Whether you’re grating it into a stir-fry, steeping it into tea, or taking it for wellness, remember: that little kick is nature’s way of saying something powerful is at work.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?