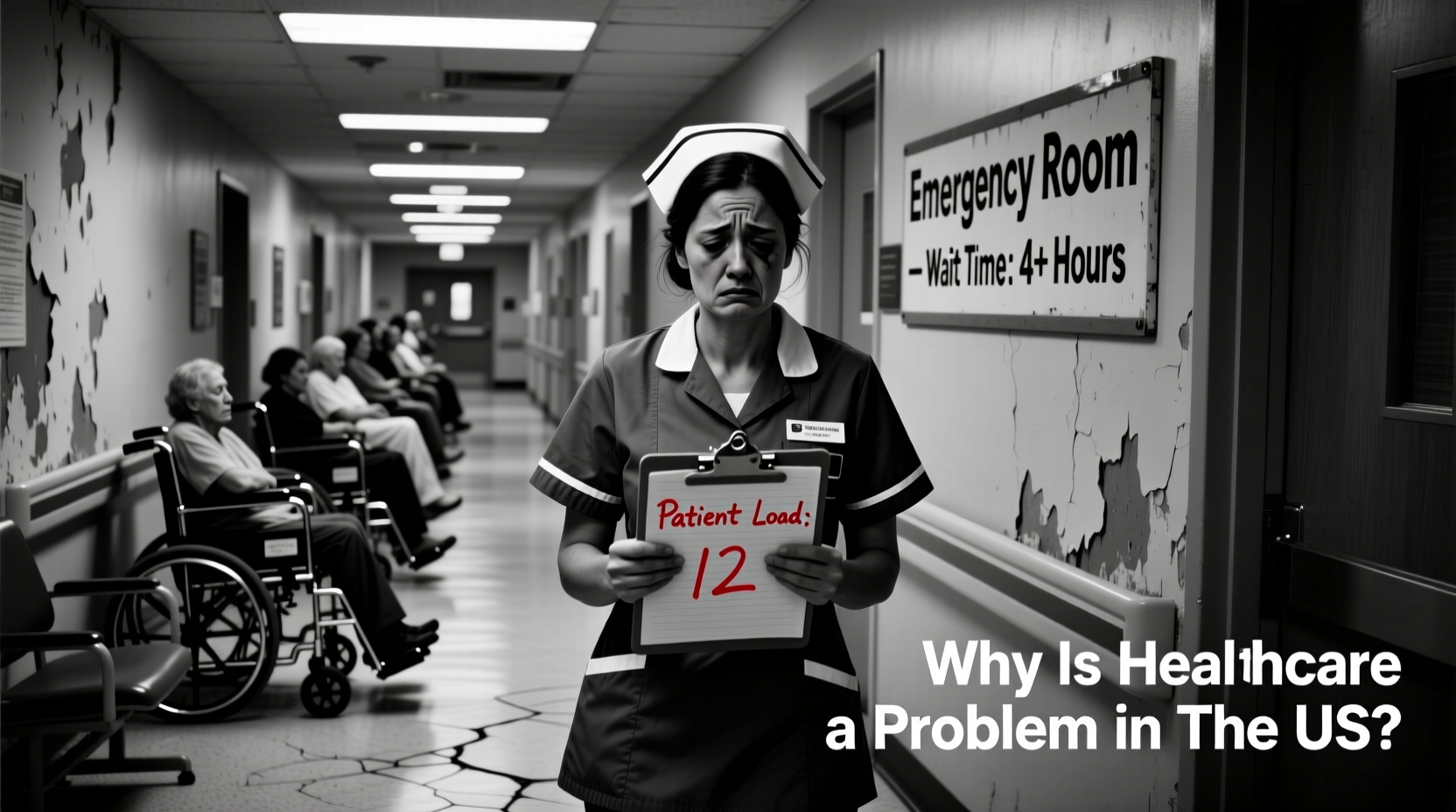

The United States spends more on healthcare per capita than any other developed nation—yet consistently underperforms in health outcomes such as life expectancy, infant mortality, and preventable disease management. Despite technological advancements and world-renowned medical institutions, millions of Americans struggle to access affordable, effective care. The root causes are deeply embedded in structural, economic, and policy-related factors that have evolved over decades. Understanding these challenges is essential for anyone seeking clarity on why healthcare remains one of the most pressing domestic issues in the U.S.

High Costs and Financial Burden

American healthcare costs are staggering. In 2023, the U.S. spent nearly $4.5 trillion on healthcare—about 17.3% of GDP. On average, individuals pay thousands annually in premiums, deductibles, and out-of-pocket expenses. Even with insurance, unexpected medical bills can lead to financial distress or bankruptcy.

Several drivers contribute to high costs:

- Administrative complexity: The fragmented system involves multiple insurers, billing codes, and paperwork, increasing overhead.

- Drug pricing: Unlike many countries, the U.S. does not negotiate drug prices at the federal level, allowing pharmaceutical companies to set high rates.

- Hospital charges: Procedures and diagnostics often carry inflated fees due to lack of price transparency and market consolidation.

- Fee-for-service model: Providers are paid per service rather than for patient outcomes, incentivizing volume over value.

Limited Access and Coverage Gaps

While the Affordable Care Act (ACA) expanded coverage to over 20 million people, approximately 26 million non-elderly Americans remain uninsured. Millions more are underinsured—carrying plans with high deductibles or limited provider networks that make care effectively inaccessible.

Rural communities face particular challenges. Over 130 rural hospitals have closed since 2010, leaving entire regions without emergency services or primary care. Telehealth has helped bridge some gaps, but broadband limitations and digital literacy barriers persist.

“Access isn’t just about having insurance. It’s about whether you can find a doctor who accepts your plan, lives nearby, and speaks your language.” — Dr. Alicia Turner, Health Policy Researcher at Johns Hopkins

Barriers to Access by Population Group

| Group | Primary Barriers | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Low-income individuals | Unaffordable premiums, Medicaid gap in non-expansion states | Delayed care, higher ER use |

| Racial minorities | Discrimination, geographic disparities, lower insurance rates | Worse outcomes in maternal health, chronic disease |

| Rural residents | Hospital closures, provider shortages | Long travel times, reduced preventive care |

| Immigrants (undocumented) | Ineligibility for public programs | Reliance on charity care or avoidance of treatment |

Inefficiency and System Fragmentation

The U.S. healthcare system is notoriously fragmented. Patients often navigate between primary care providers, specialists, labs, pharmacies, and insurers—all using different electronic systems that don’t communicate effectively. This leads to duplicated tests, medication errors, and poor coordination, especially for those with chronic conditions like diabetes or heart disease.

Unlike integrated systems in countries like the UK or Sweden, the U.S. relies on a patchwork of private and public payers, each with its own rules and reimbursement models. This fragmentation increases administrative costs and reduces care quality.

Interoperability—the ability of health IT systems to exchange data—remains limited despite federal efforts. A 2022 ONC report found that only 54% of hospitals could electronically send, receive, find, and integrate patient information from outside organizations.

Health Inequities and Social Determinants

Health outcomes in the U.S. are heavily influenced by social determinants: income, education, housing, food security, and neighborhood safety. These factors account for up to 80% of health outcomes, yet traditional healthcare delivery rarely addresses them.

For example, life expectancy can vary by as much as 20 years between wealthy and low-income neighborhoods in the same city. Black women are three times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than white women, regardless of income or education level—a disparity rooted in systemic bias and unequal treatment.

Programs that integrate social services with medical care—such as housing assistance for homeless patients or nutrition counseling for diabetics—have shown promise, but they remain underfunded and localized.

Workforce Shortages and Burnout

The U.S. faces a growing shortage of healthcare professionals, particularly in primary care, mental health, and rural areas. The Association of American Medical Colleges projects a shortfall of up to 124,000 physicians by 2034. Nursing shortages are equally acute, worsened by pandemic-era burnout and early retirements.

Burnout among clinicians is widespread. A 2023 Medscape survey found that 49% of physicians reported feeling burned out, citing excessive paperwork, long hours, and emotional strain. This affects patient care, leading to higher error rates and reduced empathy.

Step-by-Step: Addressing Provider Burnout at the Organizational Level

- Conduct regular staff well-being assessments.

- Reduce administrative burden through scribes or AI documentation tools.

- Implement flexible scheduling and mental health support programs.

- Promote leadership training focused on empathetic management.

- Encourage team-based care models to distribute workload.

Mini Case Study: Maria’s Story

Maria, a 48-year-old home health aide from Phoenix, was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes in 2021. Though she had employer-sponsored insurance, her plan required a $3,000 deductible. Insulin alone cost $200 per month after insurance. To save money, she rationed her medication—using half doses—which led to hospitalization for diabetic ketoacidosis in 2022. After discharge, she enrolled in a patient assistance program and began seeing a community health worker who helped her apply for subsidies and access free clinics. Her story reflects how cost, lack of preventive support, and fragmented care can escalate manageable conditions into crises.

Checklist: What You Can Do to Navigate the System

- Review your insurance plan annually during open enrollment.

- Ask for generic medications or patient assistance programs.

- Seek out federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) for sliding-scale care.

- Keep a personal health record to improve care coordination.

- Contact nonprofit organizations for help with specific conditions (e.g., PAN Foundation).

- Advocate for policy changes by contacting elected representatives.

FAQ

Why does the U.S. spend so much on healthcare but get poor results?

The U.S. prioritizes expensive interventions over preventive care, lacks cost controls on drugs and procedures, and fails to ensure universal access. High administrative costs and profit-driven incentives further distort efficiency and equity.

Can telehealth solve access problems?

Telehealth improves access for many, especially in mental health and follow-up visits. However, it cannot replace in-person care for physical exams or emergencies, and its benefits are limited by internet access and digital literacy.

Is single-payer healthcare the solution?

Proponents argue that a single-payer system would reduce administrative waste, control costs, and guarantee universal coverage. Critics cite concerns about wait times and tax increases. Evidence from other high-income nations suggests such systems can deliver better outcomes at lower cost—but political feasibility in the U.S. remains low.

Conclusion

The challenges facing U.S. healthcare are complex, interwoven, and resistant to quick fixes. From unsustainable costs and fragmented delivery to deep-seated inequities and workforce strain, the system often fails those who need it most. Yet solutions exist—from policy reforms and price transparency laws to integrated care models and expanded workforce pipelines. Change begins with awareness, advocacy, and informed civic engagement.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?