The sandwich is one of the most ubiquitous foods in the world—found in school lunches, delis, street carts, and fine dining reinterpretations. Simple yet endlessly adaptable, it consists of food placed between or within slices of bread. But why do we call it a \"sandwich\"? The answer lies not in ingredients or technique, but in British aristocracy, late-night gambling habits, and the legacy of a man whose name became immortalized through convenience.

The Earl Who Invented the Meal (But Didn’t Mean To)

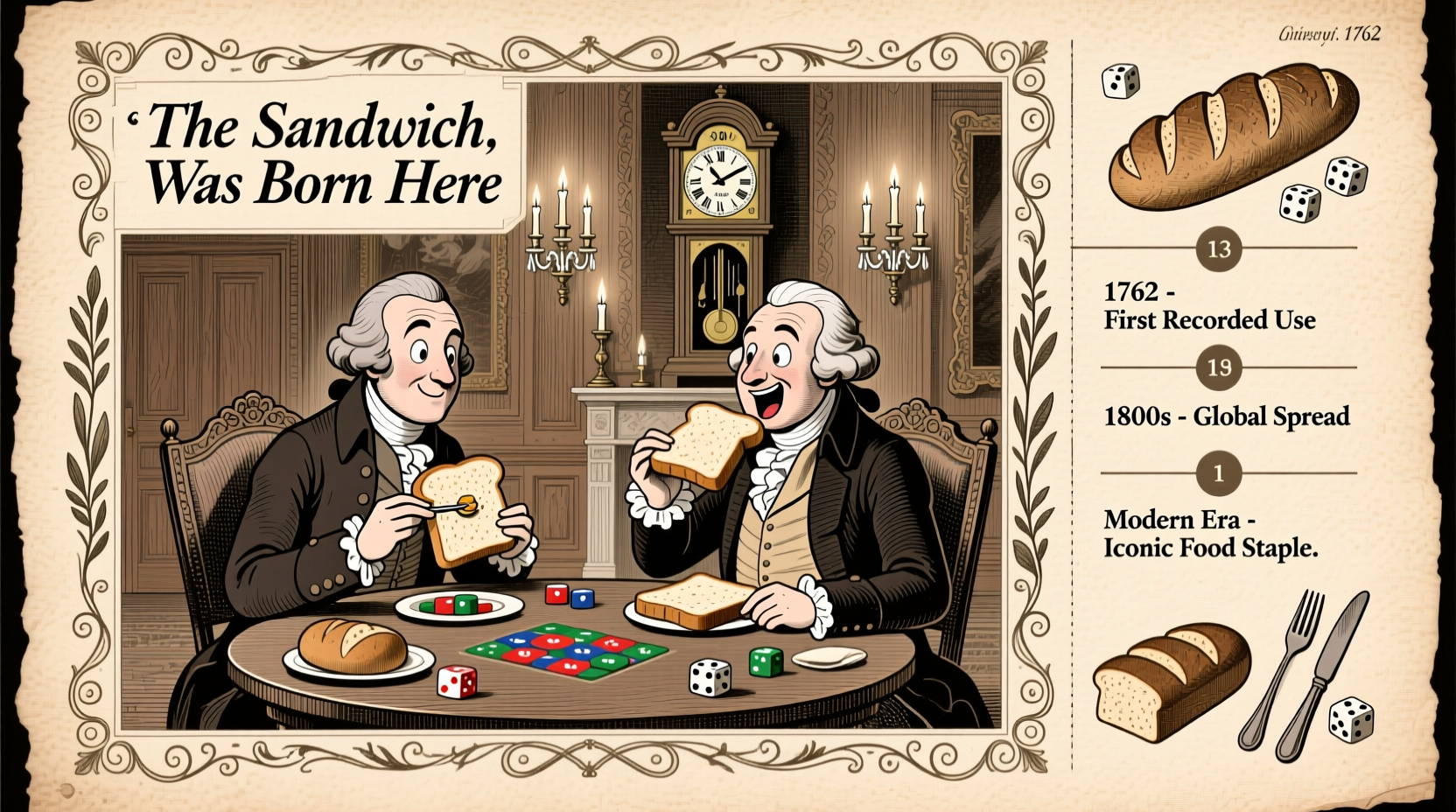

The term “sandwich” traces back to John Montagu, the 4th Earl of Sandwich, an 18th-century British nobleman with a reputation for both political influence and eccentric behavior. Born in 1718, Montagu was a powerful figure in the Royal Navy and served as First Lord of the Admiralty multiple times. However, his lasting claim to fame came not from governance, but from a personal habit born out of necessity—and indulgence.

According to historical accounts, Montagu was an avid gambler who often spent long hours at the card table. Rather than interrupt his games for a formal meal, he requested that his servants bring him meat tucked between two slices of bread so he could eat without leaving the table or soiling his cards. This practical solution allowed him to continue playing while satisfying his hunger—a small innovation with massive cultural consequences.

“Lord Sandwich would not leave the gaming-table to take his meals, but had meat brought to him on a slice of bread.” — Pierre-Jean Grosley, French Traveler, 1765

Grosley’s observation during a visit to England helped popularize the concept across Europe. As others began adopting the practice—either imitating the Earl directly or simply finding the format convenient—the food became associated with its namesake. By the late 1760s, “a sandwich” had entered common English usage.

From Aristocratic Snack to Global Staple

What started as a workaround for a busy nobleman quickly gained popularity among London’s working class and elite alike. The sandwich offered portability, minimal mess, and flexibility—qualities that made it ideal for soldiers, laborers, travelers, and students.

By the 19th century, sandwiches were a fixture in British society. Railway travel further boosted their appeal, as pre-made sandwiches became standard fare on long journeys. Cookbooks of the era began including elaborate variations, such as cucumber sandwiches for afternoon tea and hearty meat-and-mustard combinations for picnics.

The concept crossed the Atlantic with British immigrants and evolved rapidly in the United States. American ingenuity introduced new forms: the grilled cheese, the club sandwich, the Reuben, and eventually fast-food iterations like the hamburger and the sub. Today, nearly every culture has its own version—from Vietnam’s bánh mì to Mexico’s torta—proving the sandwich’s universal adaptability.

A Timeline of the Sandwich's Evolution

The journey from a single man’s dinner solution to a global food phenomenon spans centuries. Here’s a concise timeline highlighting key milestones:

- 1762: John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich, popularizes eating meat between bread during extended gambling sessions.

- 1765: French traveler Pierre-Jean Grosley documents the practice in his writings, introducing the idea to continental Europe.

- 1840s: The tradition of afternoon tea in Britain includes delicate finger sandwiches, cementing their place in social rituals.

- 1889: The first known recipe for a peanut butter sandwich appears in the U.S., later becoming a childhood staple.

- 1920s: Industrial slicing machines make uniform bread widely available, accelerating sandwich consumption.

- 1946: The submarine sandwich gains popularity in the U.S., named after naval vessels due to its shape.

- 1960s–Present: Fast food chains like Subway and Jimmy John’s turn the sandwich into a scalable, customizable business model.

Debunking Common Myths About the Sandwich Origin

Despite the well-documented link to the Earl of Sandwich, several myths persist about the food’s origins. Let’s clarify the facts:

| Myth | Reality |

|---|---|

| Sandwiches existed under that name long before the 18th century. | No recorded use of “sandwich” as a food term exists prior to the 1760s. While layered bread-and-food combinations date back to antiquity, they weren’t called sandwiches. |

| The Earl invented the concept entirely from scratch. | People have eaten food on bread for millennia (e.g., ancient Hebrews with charoset, Romans with filled bread). Montagu didn’t invent the idea—he gave it a name and social momentum. |

| The term refers to the town of Sandwich in Kent, England. | While the title “Earl of Sandwich” derives from the town, the food was named after the person, not the place. However, the town now embraces the connection with annual festivals and signage. |

How the Sandwich Changed Food Culture Forever

The sandwich did more than satisfy hunger—it redefined how people interact with meals. Before its rise, eating often required sitting down, utensils, and time. The sandwich introduced the idea of **portable, self-contained meals**, paving the way for modern concepts like meal prep, grab-and-go dining, and food-on-the-move lifestyles.

In urban environments, where time is scarce and space limited, the sandwich became a symbol of efficiency. It also democratized eating: unlike formal dinners, anyone could assemble a sandwich with minimal skill or resources. This accessibility fueled its spread across socioeconomic lines.

Chefs and home cooks alike continue to reinvent the sandwich. From gourmet brioche burgers to vegan jackfruit sliders, the format remains a canvas for creativity. Even plant-based meats and lab-grown proteins are being tested in sandwich form—proof that its evolution is far from over.

Mini Case Study: The Lunch Truck Revolution

In New York City during the 1980s, a wave of immigrant-owned lunch trucks began offering $5 sandwiches combining Middle Eastern flavors with American convenience. One vendor, Hassan Ibrahim, started selling spiced lamb and tahini on pita from a cart near Wall Street. Within five years, his “street gyro” became a staple for financial workers on tight schedules.

Hassan never set out to change food culture. But by adapting traditional recipes into sandwich form, he tapped into the same principle that drove the Earl of Sandwich centuries earlier: **efficiency meets appetite**. Today, his grandson runs a chain of fast-casual restaurants, all rooted in that original handheld idea.

FAQ: Common Questions About the Sandwich Name

Was John Montagu proud of having a food named after him?

There’s no definitive record of his feelings on the matter. Some historians suggest he may have been indifferent or even embarrassed, as the story highlighted his gambling habits. However, his family name endured in culinary history regardless.

Are there any countries where the word “sandwich” isn’t used?

Yes. In many languages, localized terms prevail. For example, in France, a sandwich is often called a *tartine* (for open-faced) or *croque-monsieur*. In Italy, *panino* is preferred. Yet the English word “sandwich” is widely understood globally due to cultural export.

Does the town of Sandwich, Kent, benefit from the association?

Absolutely. The town leans into its namesake with events like the Sandwich Festival, souvenir shops selling branded merchandise, and even a “Sandwich Trail” highlighting local eateries. It’s a rare case of a place benefiting from a homonymic food legacy.

Final Thoughts: More Than Just Bread and Filling

The sandwich is more than a meal—it’s a cultural artifact shaped by class, convenience, and chance. Its name honors a man who likely never intended to revolutionize eating habits, yet his momentary choice echoed through centuries. What began as a gambler’s shortcut became a cornerstone of modern food culture.

Every time someone grabs a quick bite between slices of bread, they’re participating in a tradition that bridges aristocracy and everyday life, history and innovation. The sandwich proves that sometimes, the simplest ideas have the longest shelf life.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?