Corned beef is a familiar sight on deli menus, holiday tables, and supermarket shelves—especially around St. Patrick’s Day. But despite its popularity, few people stop to ask: why is it called “corned” beef? After all, there’s no corn in it. The answer lies not in modern agriculture but in centuries-old food preservation practices and linguistic evolution. Understanding the term reveals a rich story of trade, necessity, and culinary adaptation across continents and cultures.

The Origin of the Word \"Corned\"

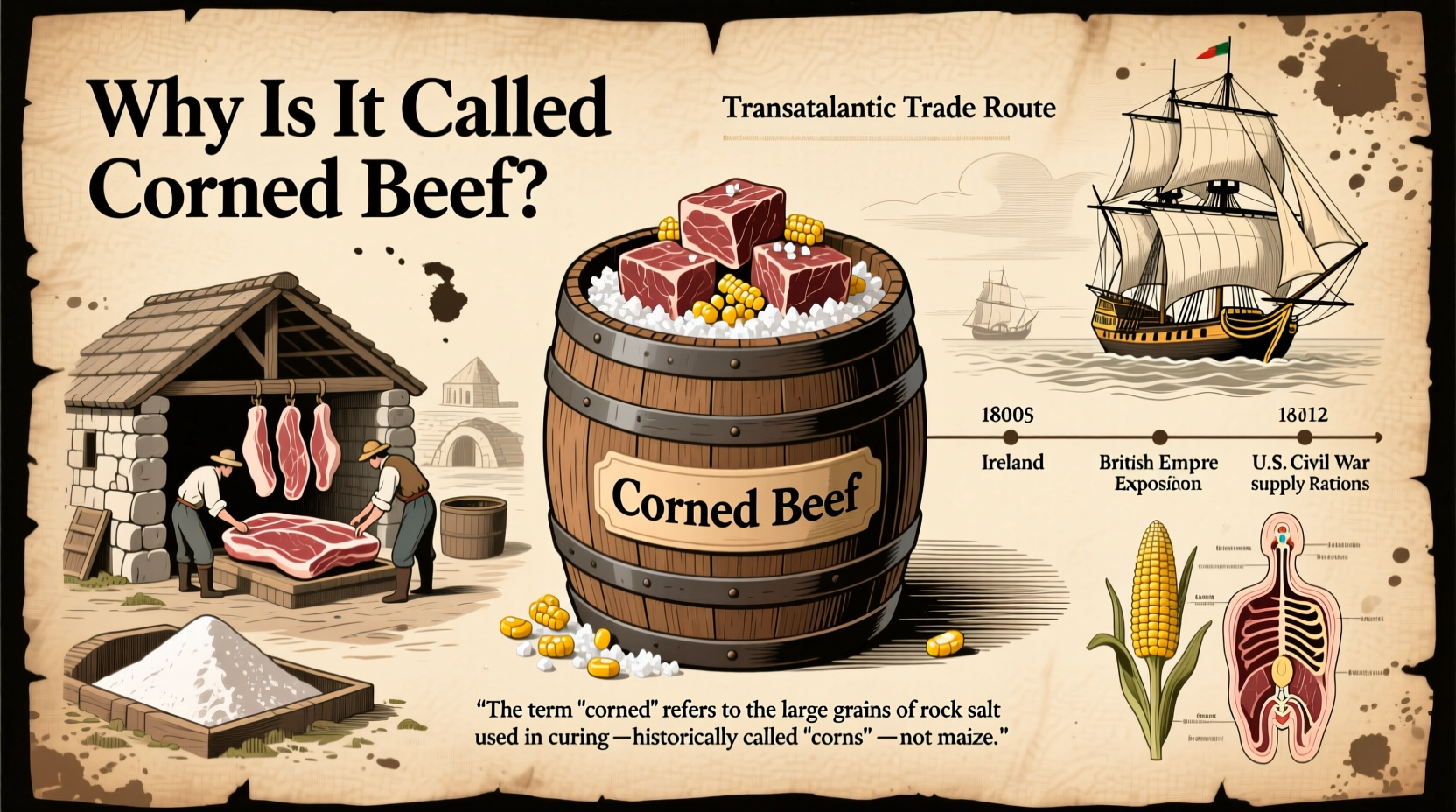

The confusion begins with the word “corn.” In American English, “corn” typically refers to maize, the golden grain native to the Americas. However, in older British and European usage, “corn” meant any small particle or grain—particularly salt crystals used in curing meat. When large-grained rock salt was rubbed into beef to preserve it, those salt grains resembled kernels or “corns,” hence the term “corned beef.”

This method of preservation dates back to at least the Middle Ages, when salting was one of the most effective ways to extend the shelf life of meat before refrigeration. Salt drew out moisture and inhibited bacterial growth, allowing beef to be stored for months. The size of the salt crystals mattered: larger grains were easier to apply evenly and dissolve slowly, ensuring thorough preservation.

A Historical Timeline of Corned Beef

The journey of corned beef spans centuries and continents, shaped by war, trade, and migration. Here’s how it evolved from a practical preservation technique into a cultural icon.

- Medieval Europe (12th–15th century): Salt-cured beef became common among sailors and soldiers due to its long shelf life. Coastal regions like Ireland began exporting salted meats using locally available sea salt.

- 17th Century: Ireland emerged as a major exporter of salted beef, particularly to Britain and its colonies. Irish producers perfected the brining method, using large vats of brine with coarse salt, sugar, and spices like bay leaves, cloves, and peppercorns.

- 18th Century: Corned beef became a staple in naval rations. The British Royal Navy relied on it during long voyages, contributing to its global spread.

- 19th Century: With industrialization, mass production of canned and vacuum-packed corned beef began. Companies like Crosse & Blackwell in England and later Hormel in the U.S. commercialized the product.

- Early 20th Century: Irish immigrants in America adopted corned beef as part of their cultural identity, especially around St. Patrick’s Day—despite its limited traditional use in Ireland itself.

Why Ireland? The Export Paradox

One of the most enduring myths about corned beef is that it’s a traditional Irish dish. In reality, historical evidence suggests otherwise. While Ireland became synonymous with high-quality corned beef exports, most Irish people did not eat it regularly. Instead, they consumed pork or dairy products, as cattle were primarily raised for milk and labor, not meat.

The export economy changed that. Wealthy Anglo-Irish landowners raised cattle and exported salted beef to England, the Caribbean, and beyond. What remained domestically was often lower-grade cuts, while the best beef was shipped abroad. This created a paradox: Ireland produced world-renowned corned beef, yet it wasn’t a staple of the local diet.

“Corned beef was more a commodity of colonial trade than a symbol of Irish cuisine.” — Dr. Máire Ní Chaoimh, Food Historian, University College Dublin

It was only in North America that Irish immigrants began embracing corned beef as a cultural touchstone. Unable to afford bacon (a traditional Irish breakfast meat), they substituted it with corned beef, which was more readily available and affordable in cities like New York. Paired with cabbage—another cheap, accessible vegetable—it became a new version of an old meal.

How Corned Beef Is Made Today

Modern corned beef differs slightly from its historical counterpart, though the core principles remain. Rather than dry-salting with coarse grains, most commercial producers use a brine solution containing water, salt, sugar, sodium nitrite (for color and preservation), and aromatic spices.

The beef—typically brisket—is submerged in this brine for 5 to 10 days, allowing flavors and preservatives to penetrate deeply. Sodium nitrite gives corned beef its signature pink hue and prevents botulism, a dangerous bacteria that can grow in anaerobic environments.

| Ingredient | Purpose | Historical Equivalent |

|---|---|---|

| Salt (NaCl) | Preservation, flavor enhancement | Coarse sea salt “corns” |

| Sugar | Balances saltiness, promotes browning | Honey or molasses (occasionally used) |

| Sodium Nitrite | Color retention, bacterial inhibition | None—color varied naturally |

| Peppercorns, Bay Leaves, Cloves | Flavor complexity | Same—spices were prized additions |

Global Variations and Cultural Adaptations

Corned beef has taken on different forms around the world, reflecting local tastes and economic conditions.

- United States: Served boiled with cabbage, potatoes, and carrots, especially on St. Patrick’s Day. Also popular in sandwiches like the Reuben.

- Caribbean: Used in fried rice, omelets, and savory pastries. In Jamaica, it’s often spiced with Scotch bonnet peppers and thyme.

- Philippines: Known as “tinned meat,” it’s a pantry staple used in dishes like *tortang carne norte* (corned beef omelet) and fried rice.

- United Kingdom: Less common today, but historically used in pies and casseroles during wartime rationing.

In many developing nations, canned corned beef remains a vital source of protein due to its long shelf life and affordability. During both World Wars, it was included in military rations and distributed through aid programs.

Mini Case Study: Corned Beef in Filipino Cuisine

In the Philippines, corned beef became widely consumed after World War II, when American troops left behind surplus canned goods. Local cooks adapted it into everyday meals, creating dishes that transformed the salty, processed meat into something uniquely Filipino. One such example is *giniling*, a ground meat dish usually made with pork, but often substituted with chopped corned beef mixed with onions, tomatoes, and soy sauce. It’s now a common comfort food served with white rice—a testament to how necessity drives culinary innovation.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is corned beef actually bad for you?

Corned beef is high in sodium and contains preservatives like sodium nitrite, which some studies link to increased cancer risk when consumed in excess. However, occasional consumption as part of a balanced diet is generally safe. Opt for low-sodium versions if you're monitoring your intake.

Why is corned beef associated with St. Patrick’s Day?

While not traditionally eaten in Ireland, Irish-American communities in the 19th and 20th centuries adopted corned beef as a festive meal. It was more affordable than bacon in urban U.S. settings and became symbolic of cultural pride and celebration.

Can I make corned beef at home without curing salt?

Yes, but the result will be less pink and may have a shorter shelf life. Use kosher salt, brown sugar, garlic, and spices in a brine, and cook it thoroughly. Without sodium nitrite, the meat will resemble pot roast more than traditional deli-style corned beef.

Checklist: How to Choose and Cook Quality Corned Beef

- Inspect the label: Look for minimal additives and recognizable ingredients.

- Rinse the beef before cooking to reduce saltiness.

- Simmer gently—do not boil—to keep the meat tender.

- Cook until fork-tender, usually 2.5 to 3.5 hours depending on size.

- Let it rest for 10–15 minutes before slicing against the grain.

- Use leftover broth for soups or grains to maximize flavor and minimize waste.

Conclusion: More Than Just a Name

The name “corned beef” may seem odd at first glance, but it opens a window into centuries of food science, global trade, and cultural reinvention. From medieval preservation techniques to modern deli counters, corned beef tells a story of human ingenuity in the face of scarcity. It’s a reminder that even the most ordinary foods carry extraordinary histories.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?