The towering granite faces of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt, and Abraham Lincoln carved into the Black Hills of South Dakota are among the most iconic symbols of American history. Yet long before sculptor Gutzon Borglum began chiseling these presidential likenesses, the mountain bore a different name—one rooted not in politics or artistry, but in commerce and law. The story of how this peak became known as Mount Rushmore is as layered as the rock itself, weaving together personal ambition, regional identity, and national memory.

The Origin of the Name \"Mount Rushmore\"

The mountain now known as Mount Rushmore was originally called “Tunkasila Sakpe” by the Lakota people—meaning “Six Grandfathers”—a sacred site within their spiritual landscape. However, when European-American explorers and settlers arrived in the region during the 19th century, they imposed new names based on their own cultural references.

The name \"Mount Rushmore\" specifically honors Charles E. Rushmore, a New York City attorney who traveled to the Black Hills in 1885 to investigate mining claims. During his visit, he reportedly asked a local guide what the mountain was called. The guide, either jokingly or spontaneously, replied that it didn’t have a name—but from then on, it would be “Rushmore’s Mountain.” The name stuck, eventually being formally adopted by the U.S. Board on Geographic Names in 1930.

“Names shape how we remember places. Mount Rushmore carries both a man’s surname and, unintentionally, a legacy far beyond his lifetime.” — Dr. Lydia Chen, Cultural Geographer

From Obscurity to National Monument: A Timeline

The transformation of Mount Rushmore from an unnamed peak to a national icon unfolded over several decades. Below is a chronological overview of key milestones:

- 1885: Charles E. Rushmore visits the Black Hills; the informal naming of the mountain occurs.

- 1923: South Dakota historian Doane Robinson proposes carving Western heroes into the Black Hills to boost tourism.

- 1924: Sculptor Gutzon Borglum is recruited for the project after Robinson sees his work on Confederate Memorial Carving at Stone Mountain.

- 1927: Construction begins on Mount Rushmore; Borglum shifts focus from Western figures to U.S. presidents symbolizing national ideals.

- 1934: George Washington’s face is completed—the first of the four presidential sculptures.

- 1936: Thomas Jefferson’s likeness is unveiled.

- 1937: Abraham Lincoln’s face is dedicated.

- 1939: Theodore Roosevelt’s image is finished.

- 1941: Work halts due to funding shortages and Borglum’s death; the original vision remains incomplete.

- 1966: Mount Rushmore is added to the National Register of Historic Places.

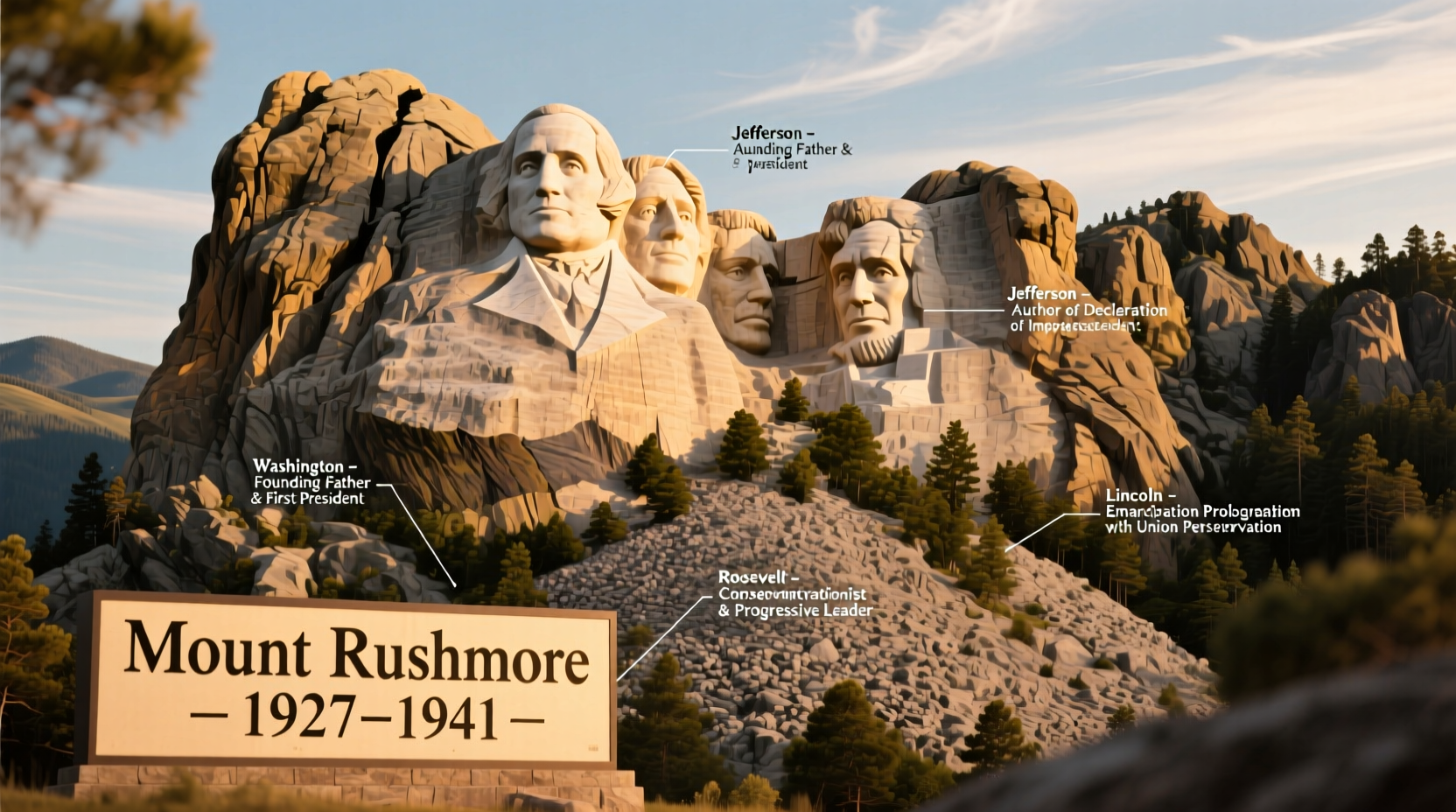

Why These Four Presidents?

Gutzon Borglum selected the four presidents not merely for fame, but for symbolic representation of pivotal chapters in American development:

- George Washington – Embodies the birth of the nation and the foundation of democratic leadership.

- Thomas Jefferson – Represents expansion and enlightenment ideals, notably through the Louisiana Purchase.

- Theodore Roosevelt – Symbolizes the rise of the United States as a global power and conservation advocacy.

- Abraham Lincoln – Stands for preservation of the Union and moral leadership during civil strife.

Borglum believed these men collectively represented the core values of liberty, democracy, and progress. He once stated, “The memorial we shall build will be a temple of democracy,” emphasizing that the monument was meant to inspire civic pride across generations.

Cultural Controversy and Indigenous Perspectives

While Mount Rushmore is celebrated by many as a patriotic landmark, it also occupies deeply contested ground—both literally and symbolically. The Black Hills were ceded to the Lakota Sioux under the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie, which guaranteed their exclusive use. Gold discoveries in the 1870s led to illegal encroachment, violating the treaty and igniting conflict, including the Battle of Little Bighorn.

In 1980, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in *United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians* that the federal government had illegally taken the land and awarded financial compensation. The Lakota have consistently refused the payment—valued today at over $1 billion with interest—insisting instead on the return of the territory.

| Aspect | Mainstream Narrative | Lakota Perspective |

|---|---|---|

| Name Origin | Honors a lawyer’s visit | Erases indigenous name Tunkasila Sakpe |

| Monument Purpose | Celebrates American ideals | Symbolizes colonial occupation |

| Land Status | Federal property | Stolen sacred land |

| Tourism Impact | Economic benefit | Commodification of trauma |

This duality underscores a broader tension in American historical memory: whose stories are preserved in stone, and whose are buried beneath them?

Preservation Challenges and Maintenance Efforts

Carved into granite prone to natural erosion and fissures, Mount Rushmore requires ongoing maintenance. The National Park Service monitors cracks using fiber-optic sensors and conducts regular inspections. Over 300 cracks have been identified in Lincoln’s face alone, some requiring epoxy sealing to prevent water infiltration.

Additionally, environmental factors such as freeze-thaw cycles and bird droppings contribute to surface degradation. A specialized team uses ropes and harnesses to access the sculpture annually for cleaning and minor repairs.

Visitor Experience and Educational Value

Today, Mount Rushmore National Memorial attracts nearly three million visitors annually. The site features a Presidential Trail, a visitor center with interactive exhibits, and evening lighting ceremonies that include narrated histories and the national anthem.

School groups often use the monument as a starting point for discussions about leadership, national identity, and the complexities of historical legacy. Ranger-led programs emphasize critical thinking, encouraging students to ask not just who is on the mountain, but why—and who is not.

Checklist: Planning a Meaningful Visit to Mount Rushmore

- Review opening hours and ticket requirements (admission is free, but parking fees apply).

- Attend the evening lighting ceremony for a reflective experience.

- Walk the Presidential Trail to view the sculpture from multiple angles.

- Visit the Lincoln Borglum Museum to understand the engineering behind the carving.

- Explore nearby indigenous cultural centers, such as the Crazy Horse Memorial, for balanced historical context.

- Respect all signage and barriers; drones and climbing are strictly prohibited.

FAQ

Was Mount Rushmore always intended to feature presidents?

No. Initially, South Dakota historian Doane Robinson envisioned figures like Lewis and Clark, Red Cloud, or Buffalo Bill. Gutzon Borglum redirected the concept toward nationally recognized presidents to give the monument broader significance.

Why wasn’t the monument completed as originally planned?

The full design included depictions of the presidents down to their waists, along with a massive entablature containing key documents like the Declaration of Independence. Funding cuts and Borglum’s sudden death in 1941 led to the project’s termination.

Is Mount Rushmore lit at night?

Yes. The memorial is illuminated nightly during summer months, typically from sunset to 9 PM. A ranger program often accompanies the lighting, detailing the monument’s history and significance.

Conclusion

Mount Rushmore is more than a mountain with carved faces—it is a convergence of ambition, identity, and controversy. Its name, derived from a chance remark to a curious lawyer, belies the weight of history now associated with it. From its geological formation millions of years ago to its role in modern debates over heritage and justice, the site continues to provoke reflection.

Understanding why it’s called Mount Rushmore means recognizing not only the individuals honored on its surface but also those whose presence predates the carving, and whose stories remain integral to its true meaning. As visitors gaze upward at the stoic visages, they are invited to look deeper—not just into the granite, but into the nation’s past and future.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?