The White House stands as one of the most recognizable buildings in the world. Nestled in the heart of Washington, D.C., it serves not only as the official residence and workplace of the President of the United States but also as a powerful symbol of American democracy. Yet for all its fame, many wonder: why is it called the White House? The answer lies in a blend of architectural choice, historical events, and evolving tradition—spanning over two centuries of national development.

Origins of the Presidential Residence

When the United States gained independence, there was no designated home for the president. George Washington, the nation’s first chief executive, lived in temporary residences in New York City and later Philadelphia while the capital was being planned. In 1790, Congress passed the Residence Act, which authorized the creation of a new federal capital along the Potomac River. This decision set the stage for the construction of an official presidential mansion.

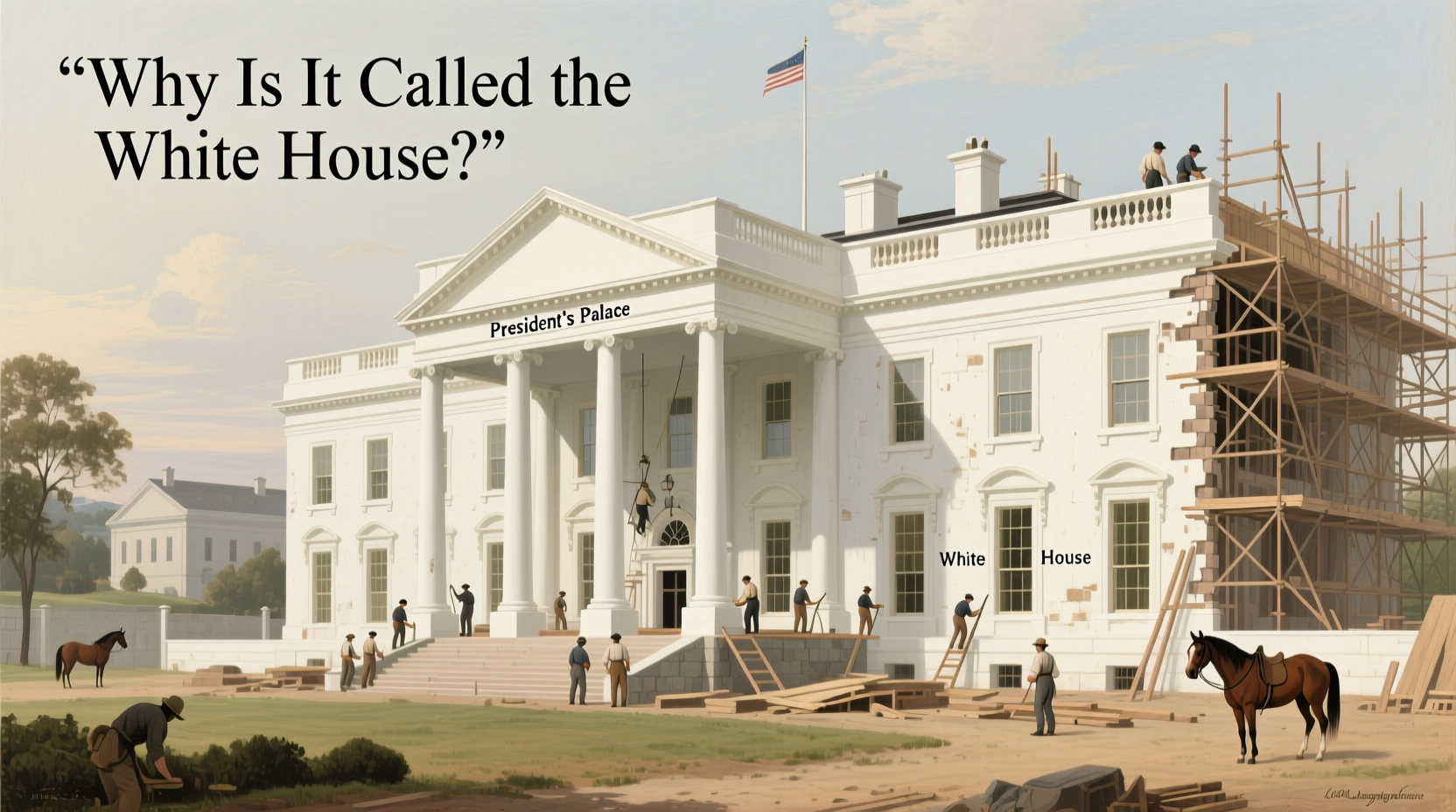

Irish-born architect James Hoban won a design competition with a neoclassical plan inspired by Leinster House in Dublin. Construction began in 1792 using Aquia Creek sandstone, a grayish stone native to Virginia. At this early stage, the building wasn’t white—it was left in its natural stone color, protected only by a lime-based whitewash to shield it from moisture.

“Hoban envisioned a dignified yet approachable residence—one that reflected republican ideals without mimicking European palaces.” — Dr. Laura Thompson, Architectural Historian

The Burning of 1814 and the Birth of a Name

The turning point in the building’s appearance came during the War of 1812. In August 1814, British forces invaded Washington, D.C., and set fire to several government buildings, including the President’s Mansion. First Lady Dolley Madison famously saved important documents and a portrait of George Washington before fleeing. By the time the flames were extinguished, the interior was gutted and the exterior blackened.

After the war, reconstruction began under Hoban’s supervision. To cover the scorch marks on the sandstone walls, workers applied a thick coat of white paint. This practical decision had lasting consequences. As the building emerged from renovation, its bright white façade became a defining feature. Over time, the nickname “White House” gained popularity among the public.

From “President’s Palace” to Official Name

In its early years, the executive mansion went by various names: “President’s Palace,” “Executive Mansion,” and even “Presidential Castle.” Some Founding Fathers feared grandiose titles might evoke monarchy, so simpler terms were preferred. However, “White House” had already entered common usage by the mid-1800s due to its distinctive appearance.

It wasn’t until President Theodore Roosevelt officially adopted the name in 1901 that “White House” became formal. He standardized stationery, signage, and correspondence to reflect the title, cementing it in government practice. Since then, every administration has used “The White House” to refer both to the building and the presidency itself.

Timeline of Naming Evolution

- 1792–1800: Construction completed; referred to as the “President’s House” or “President’s Palace.”

- 1814: Building burned by British troops; rebuilt with white-painted walls.

- 1817–1840s: “White House” increasingly used in newspapers and public discourse.

- 1850s–1900: Federal documents still use “Executive Mansion,” though “White House” dominates colloquially.

- 1901: President Theodore Roosevelt issues executive order standardizing “The White House” as the official name.

Architectural Significance and Symbolism

The White House’s color has since taken on deeper meaning. White conveys purity, transparency, and civic virtue—values central to democratic governance. Unlike royal palaces adorned with gold and red, the White House presents a restrained elegance. Its symmetry, columns, and pale exterior reflect Enlightenment ideals that shaped the young republic.

Over the decades, maintenance has preserved the white exterior through regular repainting. Approximately 570 gallons of paint are used during each full exterior repaint, a process carried out every four to eight years depending on condition. The current shade is a custom blend known as “Whisper White,” a slightly warm off-white that enhances visibility in photographs and complements the surrounding landscape.

| Era | Common Name | Reason/Context |

|---|---|---|

| 1790s–1814 | President’s House / President’s Palace | Formal designation; avoided monarchical implications |

| 1815–1850 | White House (informal) | Public adoption after post-fire painting |

| 1850–1901 | Executive Mansion (official), White House (popular) | Government preference vs. public usage |

| 1901–Present | The White House (official) | Roosevelt formalizes the popular name |

Mini Case Study: The Taft Renovation and Public Perception

In 1909, President William Howard Taft undertook a major renovation of the White House. Seeking more space and modern amenities, he expanded the West Wing and reconfigured office layouts. During construction, journalists frequently referred to the project as happening at “the White House,” reinforcing the term in national media.

A New York Times article from June 1909 noted: “The President spends his mornings in the residence proper, just east of the newly erected offices at the White House.” This casual usage illustrates how deeply embedded the name had become—even in formal reporting. By the time Taft left office, “Executive Mansion” had effectively disappeared from public use.

Frequently Asked Questions

Was the White House always white?

No. When originally constructed between 1792 and 1800, the sandstone walls were left unpainted and appeared gray. They were first painted white after the 1814 fire to conceal burn damage, and the color stuck.

Has the White House ever been another color?

There is no credible evidence that the White House has ever been painted any color other than white since 1814. Temporary scaffolding or protective coverings may alter its appearance during renovations, but the structure itself remains white.

Why didn’t they restore the original gray stone after 1814?

The fire caused significant staining and deterioration. Painting over the damaged surface was more cost-effective and durable than attempting to clean or replace large sections of stone. Additionally, the white finish quickly became associated with the building’s renewed resilience.

Practical Tips for Understanding Historical Landmarks

- Research primary sources like letters, newspapers, and government records from the era.

- Consider environmental factors—weather, fire, or material decay often influence architectural changes.

- Track linguistic shifts: slang terms can become official over time.

- Visit museums or archives related to the site for deeper context.

- Compare naming patterns across other national landmarks to identify trends.

Conclusion: More Than Just a Color

The name “White House” originated not from ideology but from necessity—a coat of paint applied to hide scars of war. Yet over two centuries, that simple act transformed into a lasting symbol of continuity, resilience, and national identity. Today, the White House represents far more than a color; it embodies the living institution of the American presidency.

Understanding its history invites us to appreciate how everyday decisions—like choosing a paint color—can ripple through time and shape cultural memory. The next time you see the White House on the news or in person, remember: its whiteness tells a story of survival, adaptation, and the quiet power of reinvention.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?