Japan’s population has been shrinking for over a decade, marking a demographic shift with profound consequences. Once a symbol of postwar economic vitality, the nation now faces a silent crisis: fewer births, an aging society, and a workforce in steady decline. This trend isn’t just a statistical anomaly—it’s reshaping Japan’s economy, culture, and long-term national strategy. Understanding the root causes and anticipating the ripple effects is essential for policymakers, businesses, and global observers alike.

Historical Context: From Boom to Bust

After World War II, Japan experienced a baby boom followed by decades of rapid industrialization and population growth. By the 1950s, fertility rates hovered around 3.0 children per woman—well above replacement level. However, this began to change in the 1970s as urbanization accelerated, women entered the workforce in greater numbers, and social norms evolved. The total fertility rate (TFR) dipped below 2.1—the threshold needed to maintain a stable population—by 1974 and has continued falling since.

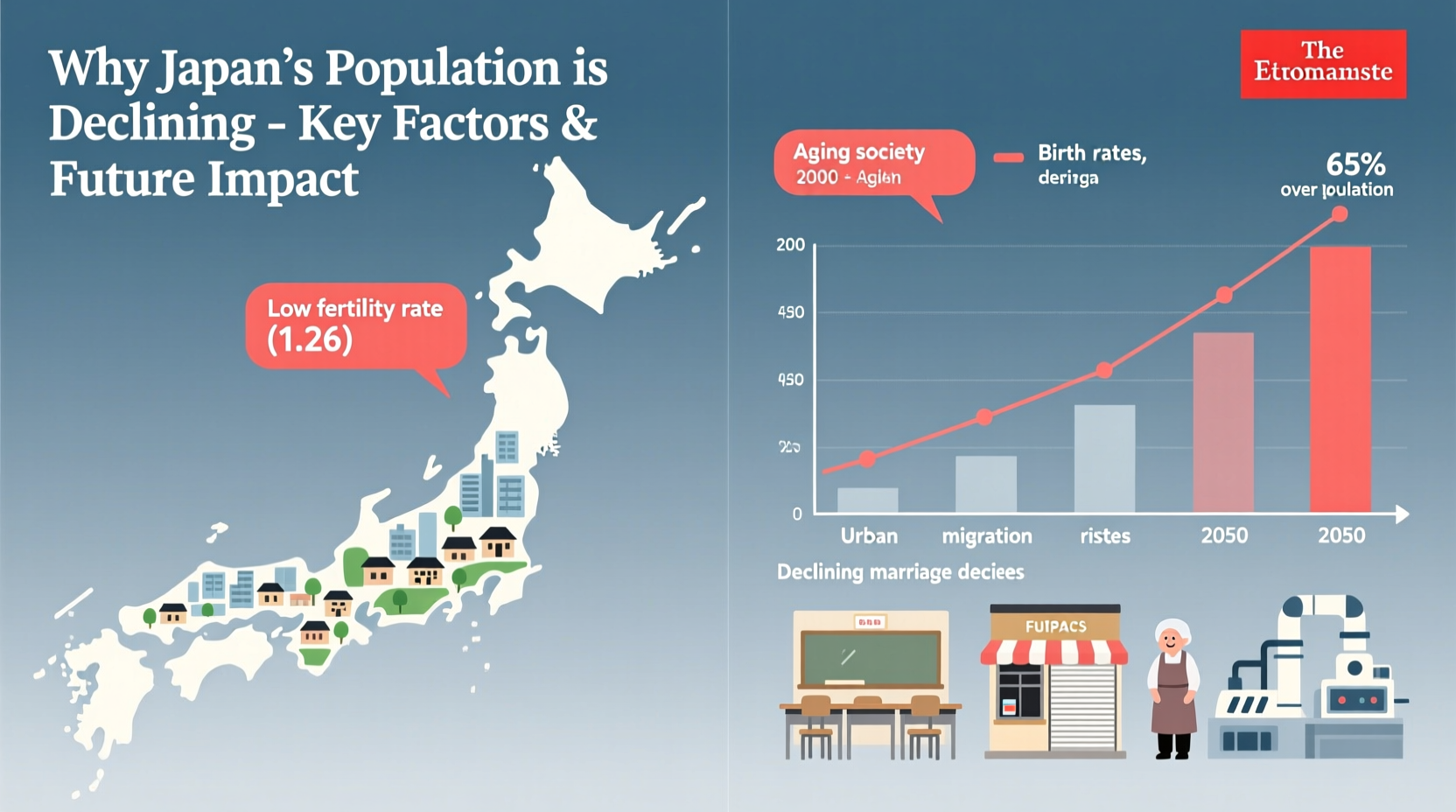

The turning point came in 2008, when Japan’s population peaked at approximately 128 million. Since then, it has declined steadily. As of 2023, Japan’s population sits around 124 million and is projected to fall below 100 million by 2050 if current trends persist. This downward spiral reflects not only low birth rates but also minimal immigration and increasing life expectancy—a combination that skews the population toward older age groups.

Key Factors Behind the Decline

Several interlocking forces are driving Japan’s demographic contraction. These include cultural, economic, and institutional challenges that make family formation less attractive or feasible for many young adults.

1. Persistently Low Fertility Rates

Japan’s fertility rate stands at about 1.26 children per woman—one of the lowest in the developed world. This figure hasn’t risen above 1.5 since the mid-1990s. A range of factors contributes to this:

- Economic insecurity: Young people face precarious employment, stagnant wages, and high housing costs, making long-term planning difficult.

- Work culture: Long working hours and limited parental leave discourage couples from having children.

- Gender inequality: Despite progress, women often bear the brunt of childcare and household duties, discouraging career continuity after childbirth.

- Changing values: Marriage and parenthood are no longer seen as mandatory life milestones, especially among urban youth.

2. Aging Population and Rising Mortality

Japan has the world’s highest proportion of elderly citizens. Over 29% of the population is aged 65 or older, and this number is expected to rise to 33% by 2036. While longevity is a public health success, it intensifies pressure on healthcare systems, pensions, and younger generations who must support retirees.

Simultaneously, death rates have begun to exceed birth rates. In 2022, Japan recorded nearly 1.5 million deaths compared to just over 770,000 births—a natural decrease of more than 700,000 people. This “demographic deficit” widens each year.

3. Limited Immigration

Unlike countries such as Canada or Germany, Japan remains highly restrictive in its immigration policies. Foreign residents make up only about 3% of the population. Cultural homogeneity, language barriers, and bureaucratic hurdles deter large-scale migration.

Although Japan has introduced new visa categories for skilled labor in sectors like agriculture and nursing care, these programs are temporary and do not lead easily to permanent residency or citizenship. Without a more open immigration framework, foreign workers cannot offset domestic population loss.

Future Economic and Social Impacts

The implications of a shrinking, aging population extend far beyond demographics—they threaten Japan’s economic model, regional stability, and global competitiveness.

Labor Shortages and Productivity Challenges

With fewer young people entering the workforce, industries from construction to healthcare face severe staffing shortages. Rural areas are particularly affected, where entire towns risk becoming “ghost communities.” Automation and robotics offer partial solutions, but they cannot fully replace human interaction in caregiving or customer service roles.

Strain on Public Finances

An aging society increases demand for pensions, medical care, and long-term support services. Government spending on social security already exceeds one-third of the national budget. With fewer taxpayers supporting more beneficiaries, fiscal sustainability becomes a growing concern.

Urban-Rural Divide and Infrastructure Decline

As younger people migrate to major cities like Tokyo and Osaka, rural regions experience depopulation. Schools close, public transportation routes disappear, and local economies stagnate. Some municipalities have resorted to offering cash incentives for relocation, but results remain limited.

“Japan’s demographic challenge is not just about numbers—it’s about maintaining social cohesion and economic dynamism in a country where every generation counts.” — Dr. Kenji Tanaka, Demographer at the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research

Government Responses and Policy Effectiveness

Japan has launched numerous initiatives to reverse the trend, including:

- Childcare subsidies and expanded daycare access

- Cash bonuses for newborns

- Workplace reforms promoting telecommuting and shorter hours

- Support for infertility treatments

Yet, results have been underwhelming. Financial incentives alone fail to address deeper structural issues like workplace inflexibility and gender disparities. A 2023 OECD report noted that while Japan spends heavily on family support, its policies lack coordination and fail to reach those most in need.

| Policy Initiative | Goal | Observed Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Monthly Child Allowance (¥15,000–¥17,000) | Reduce child-rearing costs | Moderate satisfaction; insufficient to change fertility decisions |

| Expansion of Daycare Spots | Enable maternal employment | Reduced waiting lists in cities; rural gaps remain |

| Work Style Reform Act | Limit overtime, improve work-life balance | Partial compliance; corporate culture slow to change |

| Regional Relocation Grants | Revitalize rural areas | Small uptake; limited long-term retention |

Mini Case Study: The Town of Yamatsuri

In Fukushima Prefecture, the town of Yamatsuri offers a microcosm of Japan’s demographic struggle. Once home to 8,000 residents, its population has dwindled to under 5,000, with over half aged 65+. Facing school closures and hospital downsizing, the town launched a bold experiment: offering ¥600,000 (about $4,000) to families who move there and have children.

The program attracted media attention and some new residents, but long-term success remains uncertain. Many newcomers still commute to jobs in larger cities, and infrastructure limitations hinder full integration. Still, Yamatsuri exemplifies how local governments are innovating under pressure—even if systemic change remains elusive.

Actionable Checklist: What Can Be Done?

Reversing population decline requires coordinated, multi-generational efforts. Here’s a practical checklist for stakeholders:

- Expand affordable childcare and after-school programs nationwide

- Enforce work-hour limits and promote flexible schedules

- Encourage shared parenting through paternity leave incentives

- Reform immigration laws to allow permanent settlement for skilled workers

- Invest in rural revitalization through digital infrastructure and entrepreneurship grants

- Promote gender equality in hiring, promotion, and household responsibilities

- Launch public awareness campaigns normalizing family-friendly lifestyles

FAQ

Will Japan run out of people?

No, but the population will continue shrinking. Projections suggest Japan could have as few as 70 million people by 2100 if no action is taken. While extinction is not a risk, societal functionality could be severely compromised without reform.

Why don’t Japanese people have more children?

It’s not due to a single cause. High living costs, demanding careers, lack of spousal support, and uncertainty about the future all contribute. Many young adults feel they cannot provide a stable environment for raising children.

Can technology solve Japan’s population problem?

Technology can mitigate labor shortages through automation and AI, but it cannot replace human connections, caregiving, or organic community growth. It should complement—not substitute—for pro-family policies.

Conclusion: A Call for Bold Vision

Japan’s population decline is not inevitable, but reversing it demands courage and creativity. Policymakers must move beyond piecemeal incentives and confront the deep-seated cultural and economic barriers that discourage family formation. Businesses can play a role by fostering inclusive workplaces. Citizens can advocate for change and rethink assumptions about career, marriage, and parenthood.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?