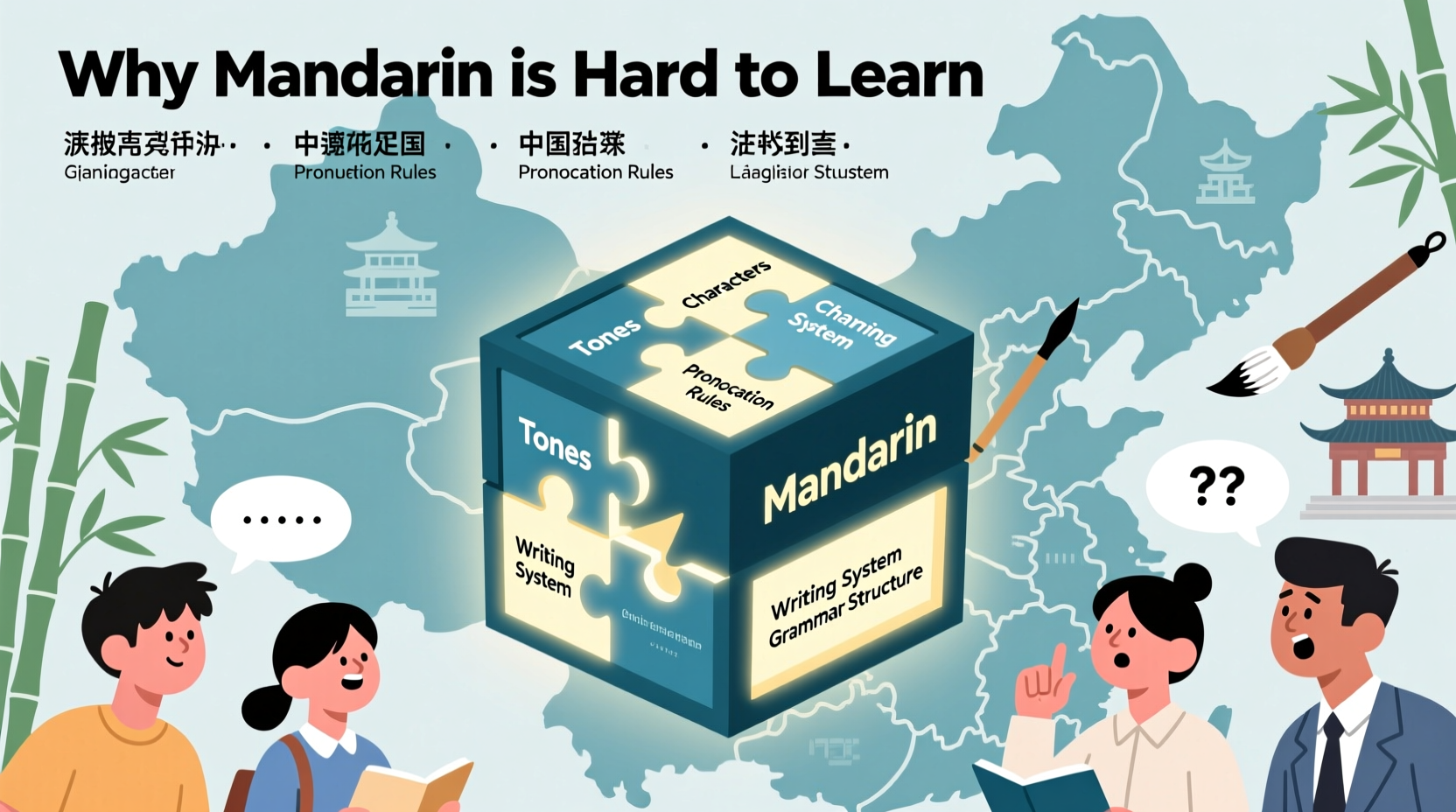

For many English speakers, learning Mandarin feels like scaling a linguistic mountain—steep, unpredictable, and often exhausting. Despite being the most spoken native language in the world, Mandarin consistently ranks among the hardest languages for Westerners to master. The U.S. Foreign Service Institute (FSI) estimates it takes approximately 2,200 class hours for an English speaker to achieve professional working proficiency—nearly twice as long as Spanish or French. But what makes Mandarin so uniquely difficult? It’s not just one factor; it’s a convergence of phonological, orthographic, grammatical, and cultural hurdles that compound the challenge.

The Tone Trap: Why Pronunciation Feels Like Walking on Eggshells

Mandarin is a tonal language, meaning the pitch contour used when pronouncing a syllable can completely change its meaning. There are four main tones and a neutral tone:

- First tone: High and level (e.g., “mā” – mother)

- Second tone: Rising (e.g., “má” – hemp)

- Third tone: Falling then rising (e.g., “mǎ” – horse)

- Fourth tone: Sharp and falling (e.g., “mà” – scold)

- Neutral tone: Light and short (e.g., “ma” – question particle)

A mispronounced tone doesn’t just sound awkward—it can lead to serious misunderstandings. Saying “mā” instead of “mà” could mean praising someone’s parenting rather than insulting them. This sensitivity demands acute auditory perception and vocal precision, both of which take months, if not years, to develop naturally.

“Tones are not optional in Mandarin—they’re foundational. Misusing them is like saying ‘ship’ instead of ‘sheep’—but worse, because the consequences are more frequent and less forgiving.” — Dr. Li Wei, Professor of Applied Linguistics, University of London

The Character Maze: Thousands of Symbols to Memorize

Unlike alphabetic systems where letters represent sounds, Mandarin uses logographic characters—each symbol represents a word or morpheme. To read a newspaper, you need to recognize around 3,000 characters. For full literacy, the number jumps to 5,000 or more.

Each character has a structure involving strokes, radicals, and components that hint at meaning or pronunciation—but these clues are inconsistent and must be learned through repetition. Take the character “好” (hǎo), meaning “good.” It combines “女” (woman) and “子” (child), suggesting harmony in family life—an etymological idea, not a phonetic rule.

Writing characters adds another layer: stroke order matters. Writing “你” (you) incorrectly may still be understood, but it marks you as a beginner and hinders handwriting recognition in digital tools.

| Language | Writing System | Characters/Letters Needed | Time to Basic Literacy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spanish | Alphabetic | 27 letters | ~600 hours |

| French | Alphabetic + diacritics | 26 letters + accents | ~750 hours |

| Mandarin | Logographic | 3,000–5,000 characters | ~2,200 hours |

Grammar That Defies Expectations

On paper, Mandarin grammar appears simpler than English. There are no verb conjugations, no plural markers, and no articles. Verbs don’t change for tense; instead, time is indicated with context or particles like “了” (le) for completed actions.

However, this simplicity masks deeper complexities. Word order is critical, and subtle changes in particle placement can alter meaning entirely. For example:

- “我吃饭了。” (Wǒ chī fàn le.) – I ate.

- “我了吃饭。” (Incorrect) – Grammatical error due to misplaced “了”.

Aspect markers like “着” (zhe) for ongoing action or “过” (guò) for past experience require nuanced understanding. These aren’t direct equivalents to English tenses but reflect how Mandarin conceptualizes time and action differently.

The Listening Challenge: Native Speed and Homophones

Mandarin speech is fast, fluid, and packed with homophones—words that sound identical but have different meanings due to tone and character. With only about 400 unique syllables (compared to over 10,000 in English), context becomes essential.

Consider “shì”: depending on tone, it can mean “is” (是), “market” (市), “affair” (事), or “room” (室). In isolation, they’re indistinguishable. Only when embedded in sentences do meanings become clear. This forces learners to rely heavily on vocabulary breadth and contextual inference—a skill that takes time to develop.

Listening to native speakers, especially in casual conversation, often feels like trying to catch raindrops in a storm. Contractions, regional accents, and rapid tone sandhi (tone changes in connected speech) make real-world comprehension significantly harder than textbook dialogues.

Real Example: Maria’s Journey with Mandarin

Maria, a software engineer from Canada, began studying Mandarin after relocating to Shanghai for work. She committed two hours daily using apps, tutors, and immersion. After six months, she could introduce herself and order food—but struggled in meetings.

During a team discussion, she said “māma” (mom) instead of “mǎmǎ” (horse), leading to confusion when discussing a project codename. Later, she misread “银行” (bank) as “很行” (very capable), causing embarrassment during a client email review.

Her breakthrough came only after nine months of consistent practice, including shadowing native speakers and writing 10 new characters daily. “I stopped thinking in English,” she says. “That’s when things started clicking.”

Practical Strategies to Overcome the Challenges

While Mandarin is undeniably difficult, it’s not impossible. Success comes from strategic, sustained effort. Here’s a step-by-step approach:

- Master tones early: Use audio drills and mimic native speakers daily. Focus on tone pairs before full sentences.

- Build character knowledge systematically: Learn high-frequency characters first. Use spaced repetition systems (SRS) like Anki.

- Immerse in listening: Start with slowed-down content (e.g., ChinesePod), then progress to native-speed media.

- Practice speaking from day one: Even basic phrases reinforce tone accuracy and build confidence.

- Engage with native speakers: Language exchange platforms like Tandem or HelloTalk provide real feedback.

Checklist: Your First 90 Days Learning Mandarin

- ✅ Learn all four tones with 50 common syllables

- ✅ Memorize 300 most-used characters

- ✅ Practice speaking for 15 minutes daily

- ✅ Listen to 30 minutes of Mandarin audio weekly

- ✅ Write 5 simple sentences every day

- ✅ Connect with a language partner once a week

- ✅ Review mistakes in a dedicated journal

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Mandarin harder than Arabic or Japanese?

For English speakers, Mandarin, Arabic, and Japanese are all classified as Category IV (hard) or V (super-hard) by the FSI. Mandarin’s tones and characters are major hurdles, while Arabic features complex script and diglossia, and Japanese combines three writing systems. Difficulty varies by learner background, but Mandarin’s tonal system often poses the steepest initial challenge.

Can I learn Mandarin without learning characters?

You can use Pinyin (the Romanization system) to speak and understand spoken Mandarin, but literacy requires characters. Most signs, menus, and official documents use characters exclusively. Relying solely on Pinyin limits your functional fluency and long-term progress.

How long does it take to become conversational in Mandarin?

With consistent study (30–60 minutes daily), most learners reach basic conversational ability in 6–12 months. Achieving comfort in spontaneous discussions typically takes 1.5 to 2 years of active practice and immersion.

Conclusion: Embrace the Challenge

Mandarin’s difficulty is real, but so is the reward. Mastering it opens doors to rich cultural experiences, business opportunities, and cognitive benefits. The journey demands patience, discipline, and resilience—but every correctly pronounced tone, every character recalled from memory, is a victory. Start small, stay consistent, and let each challenge refine your understanding. The path may be steep, but the view from fluency is unparalleled.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?