In an era defined by instant communication and endless information streams, the line between fact and fiction has blurred for millions of people. Misinformation—false or inaccurate information shared without malicious intent—has become a pervasive force shaping public opinion, influencing behavior, and undermining trust in institutions. Unlike disinformation, which is deliberately deceptive, misinformation often spreads through well-meaning individuals who unknowingly amplify falsehoods. The consequences, however, are just as damaging. From distorting scientific consensus to destabilizing democratic processes, the ripple effects of misinformation are both widespread and deep.

The Cognitive Vulnerability to False Information

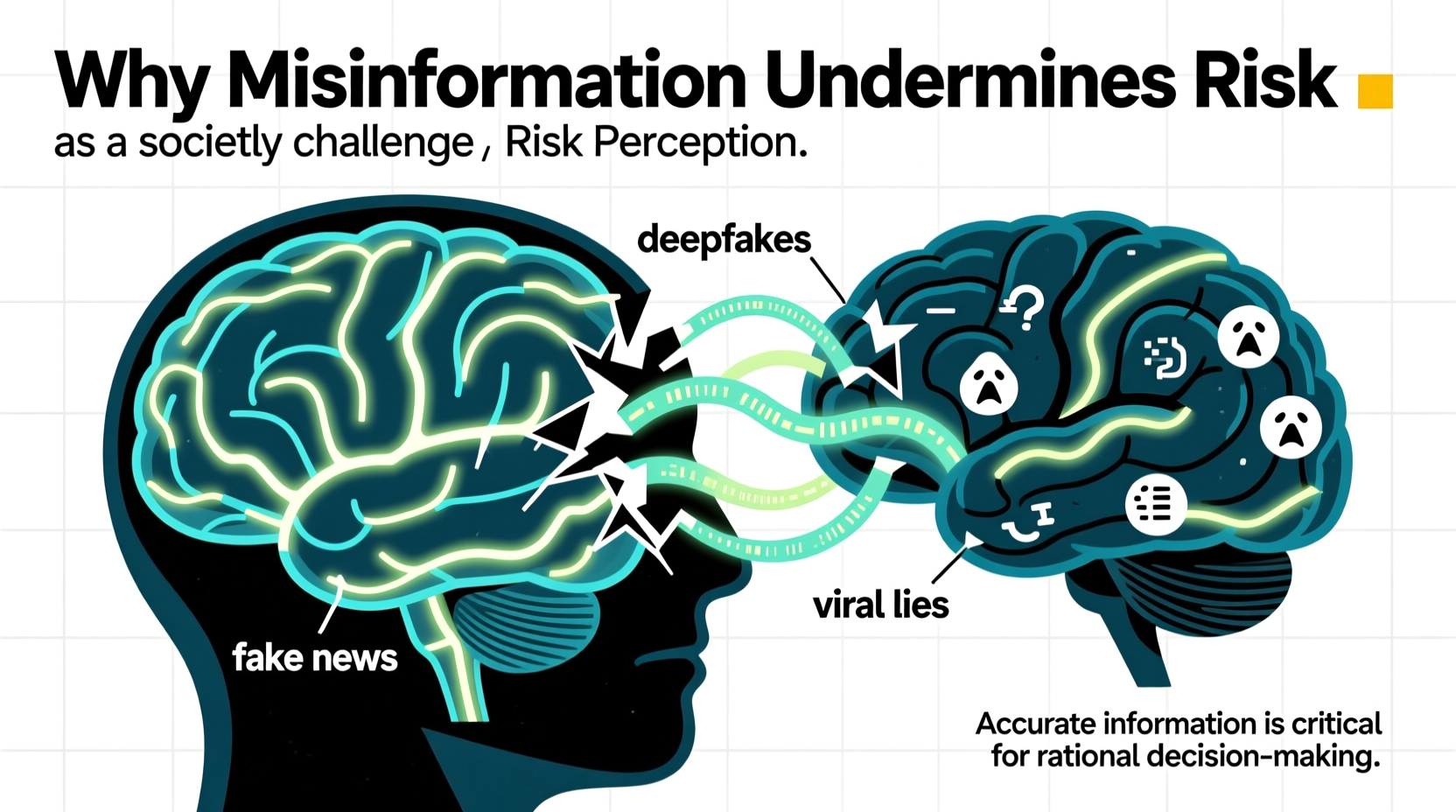

Human brains are wired to seek patterns and accept information that aligns with existing beliefs—a phenomenon known as confirmation bias. When people encounter information that supports their worldview, they're more likely to believe and share it, regardless of its accuracy. This cognitive shortcut becomes dangerous in digital environments where algorithms prioritize engagement over truth, amplifying emotionally charged or sensational content.

Misinformation exploits these psychological tendencies. A single misleading headline, doctored image, or out-of-context quote can go viral within hours, embedding itself in public discourse before fact-checkers have time to respond. Once absorbed, false beliefs are difficult to correct due to the \"backfire effect,\" where attempts to debunk misinformation actually reinforce it.

Public Health at Risk: The Case of Vaccine Hesitancy

One of the most urgent arenas where misinformation has proven deadly is public health. During the COVID-19 pandemic, false claims about vaccine development, ingredients, and side effects spread rapidly across social media platforms. Despite overwhelming scientific evidence supporting vaccine safety and efficacy, unfounded rumors led to widespread hesitancy.

A real-world example emerged in 2021 when a widely circulated myth claimed that mRNA vaccines could alter human DNA. This claim was biologically impossible—the mRNA does not enter the cell nucleus nor interact with DNA—but it gained traction among communities already skeptical of medical institutions. As a result, vaccination rates stalled in certain regions, contributing to prolonged outbreaks and avoidable hospitalizations.

“Misinformation is now a leading comorbidity in public health crises. It doesn’t just mislead—it kills.” — Dr. Maria Thompson, Epidemiologist and Public Health Advocate

Threats to Democratic Institutions

Democracy relies on informed citizens making rational choices. When misinformation floods the information ecosystem, it erodes the foundation of democratic governance. False narratives about election integrity, political candidates, or policy outcomes manipulate voter perception and diminish faith in electoral systems.

The January 6, 2021 Capitol riot in the United States was fueled in part by persistent misinformation about the 2020 presidential election being “stolen.” Despite numerous audits, court rulings, and certifications confirming the legitimacy of the results, millions believed the falsehood. This illustrates how misinformation can escalate from online chatter to real-world violence and institutional disruption.

Authoritarian regimes have long exploited misinformation to maintain power, but in open societies, the challenge lies in balancing free speech with the need to protect civic discourse from manipulation. Social media platforms, while designed for connection, often act as accelerants for divisive and false content due to their engagement-driven algorithms.

How Misinformation Spreads: A Step-by-Step Breakdown

Misinformation rarely emerges from a single source. Instead, it follows a predictable lifecycle enabled by technology and human behavior. Understanding this process helps in developing strategies to counter it.

- Origin: A false claim is created—often through misinterpretation, satire taken literally, or selective editing.

- Amplification: Influencers, bots, or partisan groups share the content, increasing visibility.

- Normalization: Repeated exposure makes the claim feel familiar, increasing perceived credibility (the \"illusory truth effect\").

- Internalization: Individuals incorporate the false belief into their worldview, resisting correction.

- Action: Belief leads to behavior—voting decisions, health choices, protests, or hostility toward others.

This cycle demonstrates why reactive fact-checking alone is insufficient. By the time corrections appear, the damage is often done. Proactive media literacy and platform accountability are essential to disrupt the chain early.

Do’s and Don’ts of Navigating Online Information

| Do | Don't |

|---|---|

| Verify sources before sharing | Trust headlines without reading the full article |

| Cross-check claims with reputable outlets (e.g., Reuters, AP) | Rely solely on social media posts or unverified blogs |

| Check the date of publication to avoid outdated context | Share emotionally charged content impulsively |

| Use reverse image search to detect manipulated visuals | Assume that high engagement equals accuracy |

| Teach children critical thinking skills early | Dismiss opposing views without evaluating evidence |

Building Resilience: A Practical Checklist

Individuals and communities can take concrete steps to reduce vulnerability to misinformation. Use this checklist to strengthen your information hygiene:

- ✅ Follow fact-checking organizations like Snopes, FactCheck.org, or the International Fact-Checking Network.

- ✅ Enable two-factor authentication on social accounts to prevent impersonation and bot takeover.

- ✅ Adjust social media settings to reduce algorithmic recommendations from unknown sources.

- ✅ Participate in digital literacy workshops or online courses on media evaluation.

- ✅ Encourage open discussions about misinformation within families and schools.

- ✅ Report blatantly false content on platforms instead of engaging or sharing.

Expert Insight: The Role of Education and Policy

While individual vigilance is crucial, systemic solutions are equally important. Experts argue that media literacy should be integrated into school curricula from an early age. Just as students learn to analyze literature or conduct science experiments, they must also learn to dissect information sources, identify bias, and assess credibility.

“We need to treat information literacy as a core life skill—on par with reading, writing, and arithmetic.” — Dr. Alan Reyes, Director of Digital Ethics at the Center for Civic Technology

On the policy front, governments and tech companies are under growing pressure to regulate content without infringing on free expression. Some countries have implemented transparency requirements for political ads and AI-generated content. Others fund independent fact-checking networks. However, enforcement remains inconsistent, and global coordination is lacking.

Frequently Asked Questions

What's the difference between misinformation and disinformation?

Misinformation refers to false information shared without intent to deceive, often due to misunderstanding or lack of verification. Disinformation is deliberately fabricated and spread with the goal of misleading others, such as in propaganda or cyber warfare campaigns.

Can fact-checking really stop misinformation?

Fact-checking plays a vital role, but it’s often reactive and reaches fewer people than the original falsehood. While effective in some contexts—like correcting record in official debates or news reports—it cannot scale to match the speed and volume of viral misinformation. Prevention through education and platform design is more sustainable.

How can I talk to someone who believes misinformation?

Avoid confrontation. Start with empathy and shared values. Ask open-ended questions like, “Where did you hear that?” or “How would we know if this were true?” Focus on the process of inquiry rather than attacking beliefs. Change often happens gradually, not in one conversation.

Conclusion: A Call to Informed Action

Misinformation is not merely a nuisance—it is a structural threat to health, democracy, and social cohesion. Its danger lies not only in what it says, but in how it shapes what people believe is true, possible, or acceptable. Recognizing the mechanisms behind its spread is the first step toward resistance. But awareness alone is not enough.

Every person who consumes and shares information holds responsibility. By cultivating skepticism without cynicism, prioritizing evidence over emotion, and demanding accountability from platforms and leaders, we can rebuild a healthier information environment. The fight against misinformation begins not in legislatures or tech boardrooms, but in our own feeds, conversations, and choices.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?