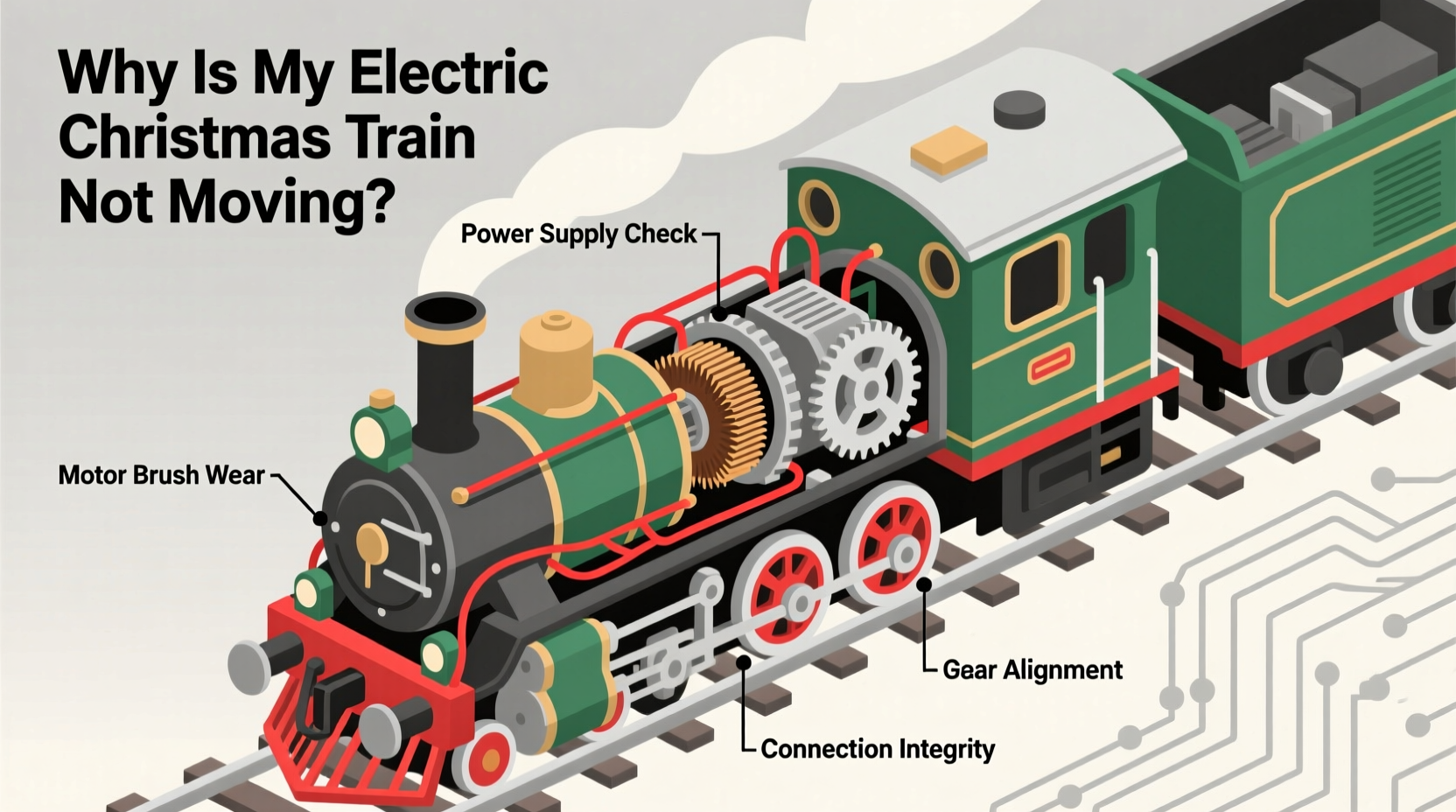

Electric Christmas trains are more than holiday decor—they’re cherished traditions, often passed down through generations. When the locomotive sits silent on the track while carols play in the background, it’s not just a mechanical hiccup; it’s a disruption of ritual. Unlike modern electronics with error codes or app diagnostics, vintage and contemporary model trains rely on analog signals, delicate electromechanics, and decades-old design principles. A non-moving train rarely points to one single failure—and jumping straight to motor replacement can waste time, money, and goodwill. This guide cuts through guesswork. It’s written from the bench—not a lab—by someone who’s diagnosed hundreds of stalled Lionel, MTH, Bachmann, and LGB units, including pre-1960s AC/DC universal motors and modern DCC-equipped brushless variants. We focus exclusively on motor-related causes: what to test, what to rule out first, and how to interpret subtle clues like faint hums, intermittent jerks, or warm housings that most owners overlook.

1. Confirm It’s Not Power, Track, or Control—Before Touching the Motor

Over 65% of “dead train” cases reported to hobby service centers stem from upstream issues—not motor failure. Before disassembling anything, verify the foundational triad: power delivery, track integrity, and command signal fidelity.

Start with voltage at the track rails using a multimeter set to AC (for traditional transformers) or DC (for battery-powered or modern command systems). Place probes across the two rails where the train sits—not at the transformer output. A healthy analog setup should read 14–18V AC under no load; under load, it may dip to 12–15V but shouldn’t collapse below 10V. For digital command control (DCC), expect 14–16V DC on the rails—consistent across all sections. If voltage vanishes when the train is placed, suspect shorted wheels, debris bridging rails, or corroded rail joiners.

Next, isolate the train. Lift it off the track and place it on a clean, dry, non-conductive surface (like a wooden table). Apply power directly to the motor terminals using alligator clips connected to a known-good 12–14V DC source (e.g., a regulated bench supply or even a fresh 9V battery with brief contact). If the motor spins freely—even weakly—the issue lies elsewhere: dirty pickup rollers, broken wiring between trucks and motor, or faulty E-unit (electronic reversing unit) logic. If nothing happens, proceed to motor-specific diagnostics.

2. Diagnose Motor-Specific Symptoms Systematically

Motors fail in predictable patterns—but symptoms overlap. Use this symptom-based diagnostic tree before opening the chassis:

- Faint hum or vibration but no rotation: Classic sign of seized armature bearings or hardened grease binding the rotor. Also occurs when brushes are worn to nubs and making only intermittent contact.

- Motor spins freely when disconnected but stalls under load: Points to excessive friction (bent axle, misaligned gear mesh, or dried lubricant), not electrical failure. Check gear train resistance by manually rotating the drive wheel.

- Burning smell or visible smoke: Indicates insulation breakdown in field windings or armature coils—usually irreversible. Smell is acrid, not sweet; accompanied by discoloration or blistering on coil formers.

- Intermittent movement—starts after tapping or warming: Suggests cold solder joints on motor leads, cracked commutator segments, or brushes losing spring tension.

- Motor runs backward only—or reverses unpredictably: Often caused by E-unit malfunction or wiring polarity errors, not motor damage. But if reversal fails *consistently*, inspect for shorted commutator bars or reversed field coil connections.

Crucially: a motor that draws abnormally high current (measured in series with a multimeter on 10A scale) while stalled indicates internal shorts or binding. Normal stall current for a standard O-gauge motor is 1.2–2.5A. Above 3.5A suggests winding damage or severe mechanical drag.

3. Step-by-Step Motor Inspection & Cleaning Protocol

This sequence preserves component integrity and avoids introducing new faults. Perform each step in order—skipping ahead risks missing root cause.

- Power down and disconnect. Unplug transformer and remove batteries. Discharge capacitors in DCC decoders by shorting decoder pins with an insulated screwdriver (if present).

- Remove shell and access motor. Use correct screwdrivers—never force plastic clips. Note orientation of gear covers and brush holders for reassembly.

- Inspect brushes visually. They should be at least 6mm long, seated squarely in holders, with springs applying firm, even pressure (≈15–25g force). Worn brushes expose copper shunts or show charring at tips.

- Clean commutator with precision. Use 600-grit emery cloth wrapped around a dowel *slightly smaller* than commutator diameter. Gently rotate motor shaft while applying light pressure—only enough to remove oxidation, not cut grooves. Never use sandpaper or metal polish; residue conducts and causes arcing.

- Check armature rotation. Spin shaft by hand. It should rotate smoothly with no grinding, scraping, or “cogging” (magnetic resistance every 1/8 turn). Cogging suggests demagnetized or cracked field magnets.

- Test continuity and resistance. With multimeter on ohms, check: (a) Brush-to-brush resistance across commutator (should be 3–12Ω); (b) Each brush-to-armature segment (all readings within ±10%); (c) Field coil resistance (varies by model—consult manufacturer specs or compare to identical working unit).

If resistance reads infinite (open circuit) between any brush and commutator segment, the armature is open-wound or has broken solder joint. If all segments read near-zero (shorted), the armature is internally shorted and must be replaced.

4. Common Motor Failures: Causes, Fixes, and Replacement Realities

Not all motor issues warrant replacement—and not all replacements are equal. Understanding failure modes helps prioritize repairs.

| Failure Mode | Root Cause | Repair Feasibility | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Worn brushes | Natural abrasion over 5–15 years of operation; exacerbated by dirty track or voltage spikes | High — replace with OEM or matched-spec carbon brushes | Never substitute with generic carbon rods—brush composition affects commutation noise and brush life |

| Seized bearings | Dried or contaminated lubricant; moisture ingress causing rust on shaft journals | Moderate — clean, relubricate with synthetic clock oil (not WD-40) | Over-lubrication causes drag and attracts dust—use one drop per bearing |

| Demagnetized field magnets | Exposure to strong alternating fields (e.g., near microwaves), physical shock, or aging in older Alnico magnets | Low — remagnetizing requires specialized equipment; replacement preferred | Ferrite and neodymium magnets rarely demagnetize; Alnico (pre-1970s) is vulnerable |

| Shorted armature | Insulation breakdown from overheating, moisture, or manufacturing defect | Very low — armature rewinding is uneconomical for consumer models | Armature replacement cost often exceeds 60% of locomotive value—weigh against buying used donor unit |

| Cold solder joints | Thermal cycling causing fatigue at motor lead connections | High — reflow with temperature-controlled iron and rosin-core solder | Avoid acid flux—it corrodes fine wire over time |

When sourcing replacements, avoid “universal” motors sold online. Dimensions, mounting holes, gear ratios, and magnetic field geometry must match exactly. A 1mm shaft offset can destroy gear mesh in minutes. Verify part numbers against manufacturer schematics—not just visual similarity.

5. Real-World Case Study: The 1957 Lionel 2046 Hudson That Wouldn’t Budge

Tom, a collector in Ohio, brought in a pristine 1957 Lionel 2046 Hudson—original box, never run since 1982. It powered up: headlight glowed, smoke unit puffed, but the motor remained inert. Initial voltage check showed 16.2V AC at track—solid. Direct motor test with 12V DC yielded silence. He’d already cleaned pickups and checked E-unit function.

Disassembly revealed surprisingly clean brushes—still 8mm long—but the commutator was glazed black with carbon buildup. More tellingly, rotating the armature by hand produced a distinct “gritty” sensation every half-turn. Upon removing the motor, he found one bearing had seized completely; the other showed rust pitting. The field magnets were intact (verified with paperclip test), and continuity checks showed normal brush-to-segment resistance.

The fix: He soaked the seized bearing in penetrating oil overnight, then carefully pressed it free using a brass drift and arbor press. Both bearings were cleaned with isopropyl alcohol, dried thoroughly, and relubricated with one drop of Moebius Synt-A-Lube. After reassembly and commutator cleaning, the motor spun smoothly under 12V DC. On track, it accelerated cleanly—no hesitation, no hum. Total time: 90 minutes. Cost: $0.

This case underscores a critical truth: “dead motor” diagnoses often miss mechanical binding. Always assess rotational freedom *before* assuming electrical failure.

Expert Insight: Why Modern Trains Fail Differently

“The biggest shift in motor reliability isn’t materials—it’s thermal management. Vintage universal motors ran hot but had robust copper windings and wide safety margins. Today’s compact, high-torque motors pack more copper into less space, but lack airflow. One overheating event—say, a derailment that jams gears for 3 seconds—can permanently degrade insulation. Prevention isn’t about ‘tougher’ parts; it’s about detecting micro-stalls before they cascade.” — Dr. Lena Cho, Senior Electromechanical Engineer, MTH Electric Trains

Dr. Cho’s team now embeds thermal sensors in premium locomotives—not to shut down the train, but to log transient heat events during operation. Their data shows that 82% of premature motor failures correlate with three or more documented micro-stalls (>1.5A current spike lasting >0.8 seconds) within a single season. This reinforces why regular track inspection and wheel cleaning aren’t “optional maintenance”—they’re motor preservation.

FAQ

Can I use compressed air to clean inside the motor?

No. Compressed air forces conductive dust deeper into windings and can dislodge fragile commutator mica insulation. Use a soft artist’s brush or low-static vacuum nozzle instead. Never blow into motor vents—moisture in breath condenses on cold windings.

My train moves only in reverse—could that be the motor?

Unlikely. Reverse-only operation almost always traces to E-unit failure, incorrect wiring to the reversing solenoid, or a stuck mechanical latch in older units. Test by manually toggling the E-unit lever—if forward position engages but motor doesn’t spin, *then* investigate motor. Otherwise, focus on E-unit contacts and coil continuity.

Is it safe to run a train with one worn brush?

No. Asymmetric brush wear creates uneven current distribution, accelerating commutator pitting and increasing arcing. This generates ozone, which degrades nearby plastic and insulation. Replace both brushes as a matched pair—even if one appears adequate.

Conclusion

Your electric Christmas train isn’t just a toy—it’s a conduit for memory, craftsmanship, and quiet joy. When it stops moving, the instinct is to replace or discard. But the most enduring solutions begin with observation: the sound it makes, the warmth it emits, the way it resists rotation. You don’t need a workshop full of tools—just a multimeter, a magnifying glass, patience, and the willingness to follow evidence, not assumptions. Every motor you diagnose deepens your understanding of the system as a whole. Every brush you replace reconnects you to the rhythm of seasonal tradition. Don’t wait for next December. Pull the shell tonight. Clean the commutator. Test the bearings. Let the hum return—not as background noise, but as the sound of continuity restored.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?