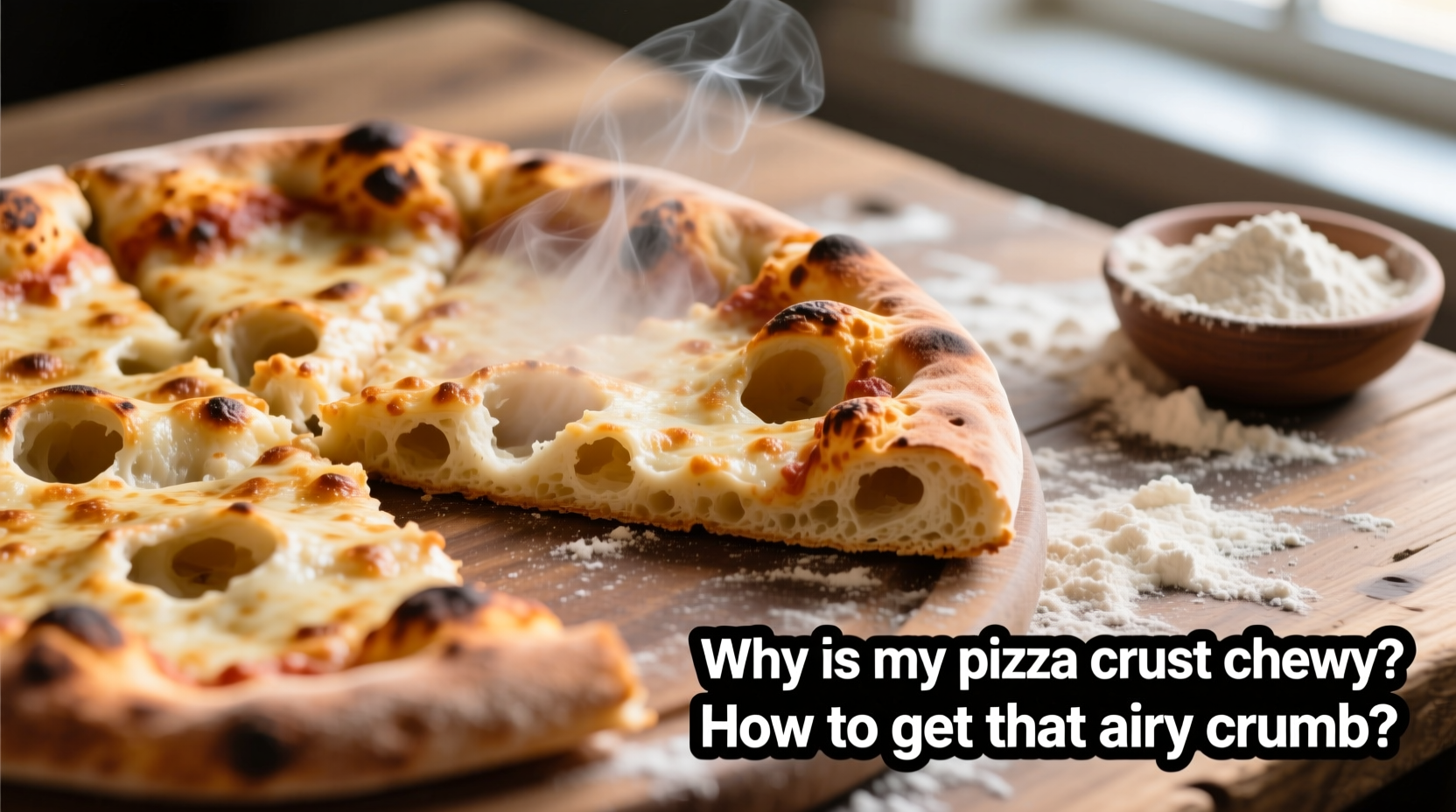

There’s nothing more satisfying than pulling a golden, blistered pizza from the oven—except when you take a bite and the crust fights back. A dense, gummy, or overly chewy texture can ruin even the most perfectly topped pie. Many home bakers struggle with this issue, often unaware that small adjustments in ingredients, technique, or fermentation can transform their crust from tough to tender, with an open, airy crumb full of irregular holes and delicate structure.

The dream of a crisp exterior giving way to a soft, elastic interior isn’t reserved for pizzerias with wood-fired ovens. With the right understanding of dough science and baking principles, you can replicate that ideal texture at home. Let’s explore what causes chewiness, how to avoid it, and the exact steps to create a light, flavorful, and beautifully textured crust.

Understanding Chewiness: The Science Behind Dense Crusts

Chewiness in pizza crust typically stems from one or more of three root causes: excessive gluten development, under-fermentation, or improper baking. While gluten is essential for structure, too much—or poorly managed gluten—leads to a tight, rubbery network that resists tearing and lacks tenderness.

Fermentation plays a critical role in both flavor and texture. During fermentation, yeast consumes sugars and produces carbon dioxide, which forms air pockets in the dough. Simultaneously, enzymes break down starches into simpler sugars and proteins into amino acids, contributing to browning and tenderness. Without sufficient fermentation time, the dough remains dense and underdeveloped, resulting in a gummy crumb.

Baking temperature and method also influence crust texture. Low oven temperatures fail to create rapid steam expansion (known as “oven spring”), preventing the dough from rising fully. This leads to collapsed air pockets and a compact interior.

The Role of Hydration and Flour Type

Hydration—the ratio of water to flour by weight—is one of the most impactful variables in dough texture. Higher hydration doughs (65% and above) are more challenging to handle but yield a more open, airy crumb. However, if not properly fermented or kneaded, they can become sticky and collapse during baking, leading to uneven textures.

Flour choice directly affects gluten formation. Bread flour, with 12–14% protein, creates stronger gluten networks than all-purpose flour (10–11%). While this strength supports large bubbles in well-managed dough, it can also result in toughness if overworked or under-fermented.

For a balanced approach, many artisan bakers use a mix of flours—such as blending Italian “00” flour with all-purpose—to achieve extensibility (stretchiness) without excessive elasticity (spring-back). “00” flour is finely milled and ideal for thin crusts, allowing for easier stretching and better oven spring.

| Flour Type | Protein Content | Best For | Texture Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| All-Purpose Flour | 10–11% | Beginners, moderate chew | Soft, slightly chewy |

| Bread Flour | 12–14% | High-oven-spring crusts | Dense, chewy (if overused) |

| “00” Flour (Italian) | 11–12% | Neapolitan-style pizza | Tender, airy, crisp exterior |

| Whole Wheat Blend | 13–14% (but less glutenin) | Nutty flavor, hearty crust | Denser, less rise |

Mastering Fermentation: Time, Temperature, and Yeast Control

Fermentation is where flavor and texture are born. A slow, cold ferment (also called retarding) allows enzymes and yeast to work gradually, breaking down complex molecules and creating gas pockets that define an airy crumb.

Room-temperature fermentation (70–75°F) typically takes 8–12 hours. Cold fermentation in the refrigerator extends this to 24–72 hours. The longer fermentation enhances flavor complexity and improves dough handling due to increased extensibility.

Using too much commercial yeast speeds up fermentation but sacrifices quality. Rapid rises produce less acidity, fewer flavor compounds, and weaker gas retention. Instead, use minimal instant yeast—often just 0.2–0.5% of flour weight—and let time do the work.

“Time is the most powerful ingredient in pizza dough. A 72-hour cold ferment transforms simple flour and water into something alive, flavorful, and full of character.” — Marco Stabile, Artisan Pizzaiolo & Instructor

Step-by-Step Guide to Optimal Fermentation

- Mix dough: Combine flour, water (65–70% hydration), salt, and a small amount of yeast. Mix until shaggy, then rest 30 minutes (autolyse).

- Knead gently: Use a stretch-and-fold technique over 2–3 sessions in the first 90 minutes to develop gluten without overworking.

- Bulk ferment: Let rise at room temperature for 2 hours, covered.

- Divide and shape: Portion dough into balls, seal seams, and place in oiled containers.

- Cold ferment: Refrigerate for 48–72 hours. This slows yeast activity while enzymes continue working.

- Warm up before baking: Remove dough 2–3 hours before use to allow it to reach room temperature and regain elasticity.

Avoiding Common Dough Mistakes

Even with perfect ingredients and timing, execution errors can sabotage your crust. Here are frequent missteps and how to fix them:

- Over-kneading: Excessive mechanical mixing strengthens gluten too much, making dough tight and resistant. Use hand mixing or low-speed mixer for no more than 5–7 minutes.

- Under-proofing: Dough that hasn’t fermented long enough lacks gas bubbles and collapses under heat. It bakes dense and gummy. Always look for a puffy, jiggly texture before baking.

- Rolling instead of stretching: Rolling pins compress air pockets. Stretch dough by hand or toss gently to preserve bubbles.

- Baking at low temperatures: Home ovens often max out at 500–550°F, but you need every degree. Preheat your oven and baking surface (stone or steel) for at least 45 minutes.

- Overloading toppings: Too much sauce, cheese, or wet ingredients weigh down the dough and prevent proper rise. Less is more.

Do’s and Don’ts of Pizza Crust Preparation

| Do | Don't |

|---|---|

| Use a scale for precise measurements | Measure flour by volume (cups)—it's inconsistent |

| Stretch dough by hand to preserve air | Use a rolling pin that flattens bubbles |

| Preheat oven and baking steel for 1 hour | Bake on a cold tray or rack |

| Ferment dough 24–72 hours in fridge | Rush fermentation with extra yeast |

| Let dough warm up before shaping | Work with cold, stiff dough |

Real Example: From Chewy to Champion-Worthy

James, a home cook in Portland, spent months frustrated by his consistently tough crusts. He used bread flour, mixed by hand, and baked at 475°F after a single 2-hour rise. His pizzas tasted good but felt like chewing gum.

After researching fermentation and adjusting his process, he switched to a 68% hydration dough using half “00” and half all-purpose flour. He reduced yeast to 0.3% and began cold fermenting dough for 48 hours. He preheated a baking steel at 500°F for an hour and stretched dough gently by hand.

The difference was immediate. His next pizza had a blistered, charred edge and a soft, hole-riddled interior. The crust tore easily with a clean pull, and the chew was pleasant—not aggressive. James now hosts monthly pizza nights, and guests consistently mistake his oven for a professional setup.

Essential Checklist for Airy, Non-Chewy Crust

Follow this checklist to ensure optimal results every time:

- ✅ Measure ingredients by weight using a digital scale

- ✅ Use 65–70% hydration based on flour type

- ✅ Incorporate a 24–72 hour cold fermentation

- ✅ Limit instant yeast to 0.2–0.5% of flour weight

- ✅ Perform 2–3 sets of stretch-and-folds during bulk ferment

- ✅ Shape dough gently; avoid degassing

- ✅ Allow dough to come to room temperature before baking

- ✅ Preheat oven and baking surface for at least 45 minutes

- ✅ Bake at the highest possible temperature (ideally 500°F+)

- ✅ Keep toppings minimal and dry (blot wet ingredients)

Frequently Asked Questions

Why does my pizza crust taste bland even when it looks good?

Blandness usually indicates insufficient fermentation. Salt enhances flavor, but fermentation develops depth. Extend cold fermentation to 48–72 hours to allow lactic acid and other flavor compounds to form. Also, ensure you're using enough salt—typically 2–3% of flour weight.

Can I make great pizza without a pizza stone or steel?

You can, but results will vary. A heavy baking sheet preheated in the oven helps mimic a stone. Avoid glass or thin pans—they don’t retain heat well. For best results, invest in a baking steel or cordierite stone, which absorb and radiate heat rapidly, promoting crispness and oven spring.

Is chewy crust ever desirable?

Yes—chewiness is a hallmark of New York-style and some Sicilian pies. But it should be balanced: elastic yet tender, not tough or gummy. If your crust sticks to the roof of your mouth, it’s over-developed or under-baked. True chew comes from skillful fermentation and baking, not poor technique.

Final Thoughts: Elevate Your Homemade Pizza Game

A chewy crust doesn’t have to be the norm. By understanding the interplay between flour, water, time, and heat, you gain control over the final texture. The goal isn’t just to avoid chewiness—it’s to cultivate a crust that sings with balance: crisp where it should be, tender within, and full of character from a well-fermented dough.

Small changes yield dramatic results. Start with extending fermentation, adjusting hydration, and mastering your oven’s limits. Each bake becomes a lesson, refining your intuition and technique. Before long, you’ll produce pizzas that rival your favorite pizzeria—all from your own kitchen.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?