Homemade soap making is both an art and a science. When your carefully crafted bar breaks apart at the first use, crumbling like dry cake, it’s more than frustrating—it’s a sign that something in the formulation went off track. One of the most common culprits? Incorrect lye and oil ratios. Understanding how these components interact is essential to producing a durable, moisturizing, and long-lasting bar. This guide walks you through the root causes of crumbly soap, how to diagnose imbalances, and—most importantly—how to correct them using precise, actionable steps.

Why Soap Becomes Crumbly: The Science Behind the Breakdown

Soap is created through saponification—a chemical reaction between fats (oils) and sodium hydroxide (lye). When balanced correctly, this process yields glycerin and soap molecules that bind into a stable, solid matrix. But when the ratio is skewed, structural integrity fails.

Crumbly soap typically results from one or more of the following:

- Lye excess (high pH): Too much lye leads to incomplete fat conversion, leaving free alkali that weakens the bar and irritates skin.

- Oil deficiency: Not enough oils mean insufficient fatty acids to react with lye, reducing binding strength.

- Overheating or rapid trace: High temperatures or aggressive mixing can cause premature thickening, trapping air and creating fragile texture.

- Poor curing conditions: Drying too fast in low humidity or high heat can cause internal stress and cracking.

- Hard oil dominance: Overuse of brittle fats like coconut or palm kernel oil without balancing emollients like olive or avocado oil reduces flexibility.

A crumbly bar isn’t just structurally unsound—it may also be unsafe if lye-heavy. Always test pH before use. A properly made soap should have a pH between 8 and 10.

Diagnosing the Problem: Is It Lye or Oil Imbalance?

Before adjusting your recipe, determine whether the issue stems from excess lye, insufficient oils, or external factors like temperature or timing.

Start with a visual and tactile assessment:

- Does the soap crack during unmolding or within days of cutting?

- Does it feel chalky or dusty on the surface?

- Does it dissolve quickly in water or lack a creamy lather?

If yes, suspect a formulation imbalance. Confirm with a simple phenolphthalein test or pH strip. A reading above 10 suggests lye dominance.

Next, audit your recipe. Did you measure lye by volume instead of weight? Did you substitute oils without recalculating lye requirements? Even a small miscalculation—like using 5 oz of lye instead of 4.8 oz for 32 oz of oils—can throw off the entire batch.

“Precision in measurement is non-negotiable in soap making. A gram too much lye can ruin a batch and compromise safety.” — Dr. Linda Farrow, Cosmetic Chemist and Formulation Consultant

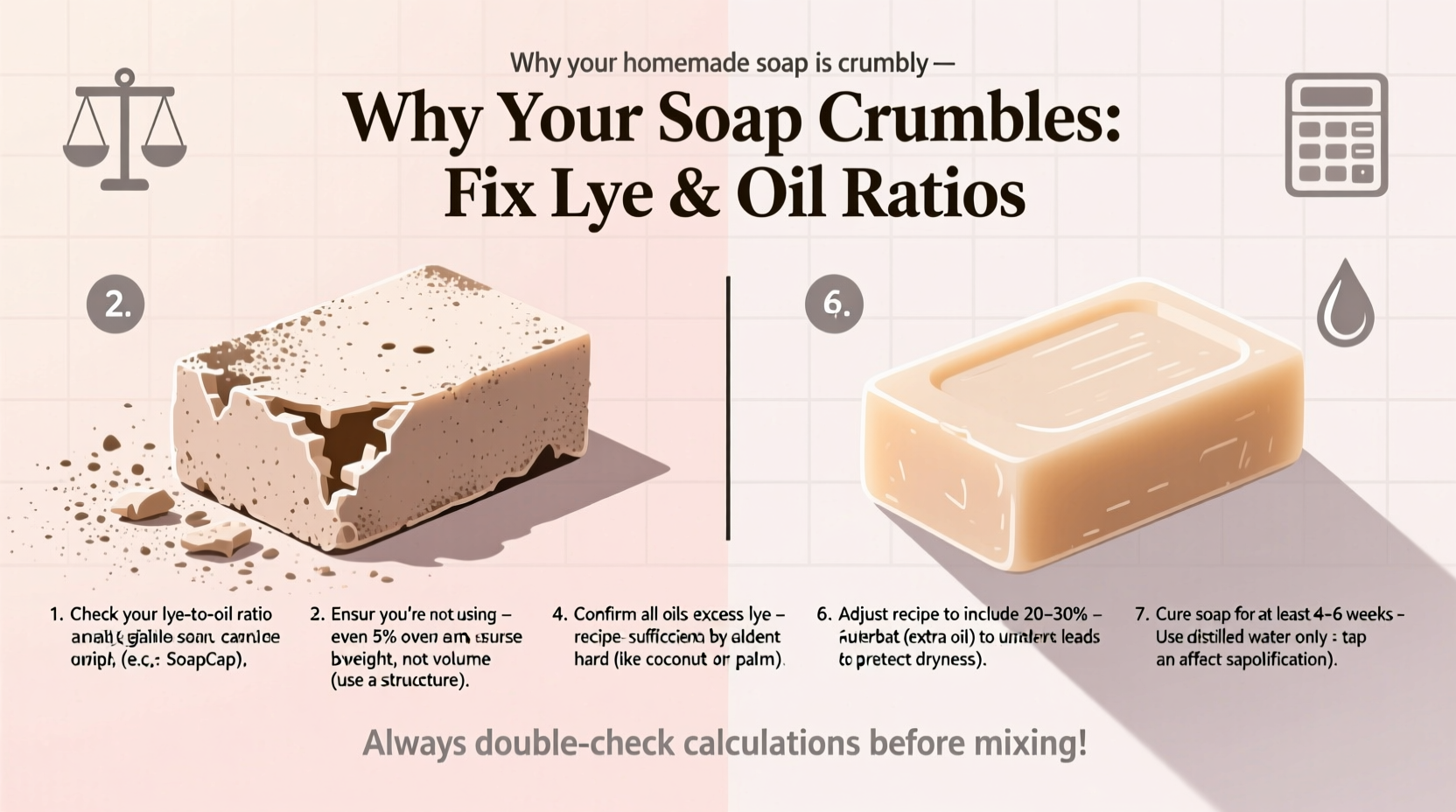

Step-by-Step Guide to Fixing Lye and Oil Ratios

Correcting crumbly soap starts with recalibrating your formulation. Follow this detailed sequence to ensure balance, safety, and quality.

- Revisit Your Original Recipe

Write down every oil used, their weights, and the amount of lye and water. Include any additives like clays or butters. - Run It Through a Lye Calculator

Use a trusted tool like Bramble Berry’s Lye Calculator or Soapee. Input each oil and its weight. Ensure the calculator accounts for SAP (saponification) values—the amount of lye needed to convert each oil into soap. - Check for Superfatting Errors

Superfatting means adding extra oils beyond what the lye can saponify, leaving moisturizing free fatty acids. Typical range: 5–8%. If your superfat is below 3%, the soap may be harsh and brittle. Above 10%, it may soften and spoil faster. Adjust accordingly. - Verify Measurements

Weigh all ingredients—including lye and water—with a digital scale accurate to 0.1 grams. Never use measuring cups for lye. - Adjust Oil Profile for Durability

Balance hard and soft oils:- Hard oils (solid at room temp): Coconut, palm, cocoa butter – contribute hardness and lather.

- Soft oils (liquid): Olive, sunflower, sweet almond – add conditioning and pliability.

- 30% coconut oil (for lather)

- 60% olive oil (for smoothness)

- 10% shea butter (for creaminess)

- Recalculate Lye Amount

After adjusting oils, recalculate lye. Example: 500g of mixed oils with a 5% superfat may require 68.4g of NaOH. Use the exact figure from the calculator. - Test a Small Batch

Make a 500g test batch using corrected ratios. Monitor trace time, gel phase, and final texture. Cure for four weeks before evaluation. - Evaluate and Refine

Assess hardness, lather, and feel after cure. If still brittle, increase soft oils by 5% and reduce hard oils proportionally. Repeat until optimal.

Do’s and Don’ts: Oil and Lye Management Best Practices

| Do | Don’t |

|---|---|

| Always use a digital scale for lye and oils | Measure lye by volume (spoons or cups) |

| Double-check SAP values when substituting oils | Swap oils without recalculating lye |

| Maintain 5–8% superfat for balanced bars | Go below 3% superfat for “extra cleansing” bars |

| Stir gently once emulsification begins | Blend aggressively to force trace |

| Cure soap in a cool, dry, ventilated area | Store in sealed plastic or humid bathrooms |

One common mistake is assuming that more coconut oil equals better lather. While true to a point, exceeding 35% often results in a drying, brittle bar. Balance is key.

Mini Case Study: From Crumbly Fail to Award-Winning Bar

Sarah, a home crafter in Vermont, struggled for months with soap that cracked within hours of unmolding. Her original recipe used 50% coconut oil, 30% palm, and 20% olive oil, with lye measured using kitchen spoons. After testing pH and finding levels near 11.5, she realized her lye was excessive.

She recalibrated: switched to weighing all ingredients, reduced coconut oil to 28%, increased olive oil to 62%, added 10% avocado oil, and set superfat at 6%. She used a lye calculator to determine the exact NaOH requirement—67.2g for 1000g of oils.

The new batch traced smoothly, gelled evenly, and cured into a firm yet creamy bar. At her local farmers’ market, customers praised its rich lather and gentle feel. Sarah now sells 50+ bars monthly—proof that precision transforms failure into success.

Essential Checklist for Balanced, Non-Crumbly Soap

Before starting your next batch, run through this checklist to avoid common pitfalls:

- ✅ Weigh all oils and lye using a calibrated digital scale

- ✅ Use a reliable lye calculator with updated SAP values

- ✅ Confirm superfat between 5% and 8%

- ✅ Limit coconut oil to 35% or less unless counterbalanced with liquid oils

- ✅ Mix at consistent room temperature (70–75°F / 21–24°C)

- ✅ Avoid over-blending; aim for light to medium trace

- ✅ Insulate mold lightly if encouraging gel phase, but monitor for overheating

- ✅ Cure bars for 4–6 weeks in a dry, airy space

- ✅ Test pH before use (ideal: 8–10)

- ✅ Document all variables for future reference

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I save a crumbly batch of soap?

If the soap is only slightly brittle and pH-safe, you can rebatch it. Grate the soap, add a small amount of water or milk, and melt slowly in a crockpot. Stir in 1 tbsp of olive oil per 500g to improve texture. Pour into molds and let re-cure for 3–4 weeks. Avoid rebatching if pH is above 10, as free lye cannot be neutralized this way.

Why did my soap crack on top?

Surface cracks usually indicate overheating during gel phase. The center heats faster than the edges, causing expansion and splitting. To prevent this, avoid heavy insulation, especially in warm rooms. You can also stick blend less vigorously and pour at lower trace. Minor cracks don’t affect usability but may signal internal stress.

Does water amount affect crumbliness?

Yes. Using too little water can lead to uneven saponification and lye pockets, weakening the bar. A standard lye solution uses a 2:1 to 3:1 water-to-lye ratio. Some advanced makers use “water discounting” for faster trace, but this increases risk if not done carefully. Beginners should stick to full water amounts until consistency improves.

Final Thoughts: Mastery Through Precision and Patience

Crumbly soap isn’t a dead end—it’s feedback. Each batch teaches you more about the delicate equilibrium between chemistry and craftsmanship. The root cause often lies in overlooked details: a misread measurement, an unadjusted substitution, or an impatience with the process. By respecting the science of saponification and methodically refining your approach, you’ll move from broken bars to beautifully balanced ones.

Remember: soap making rewards diligence. Accurate scales, verified calculations, and thoughtful oil selection aren’t optional extras—they’re the foundation of success. Whether you’re crafting for personal use or building a brand, getting the lye and oil ratios right ensures safety, longevity, and satisfaction.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?