It’s a familiar scene: you step into the shower, turn on the water, and within seconds, the curtain begins creeping toward you, clinging to your legs as if trying to escape the tub. You’ve weighed it down with magnets, added heavier liners, even taped the edges—but still, it billows inward. This isn’t just bad design or faulty materials. It’s physics in action. The real culprit lies in the invisible forces of fluid dynamics at play every time you shower. Understanding why this happens doesn’t just satisfy curiosity—it can help you find smarter solutions.

The Core Principle: Airflow Creates Pressure Differences

When your shower runs, especially with hot water, several things happen simultaneously. Steam rises, water droplets fly, and air begins to move rapidly around the enclosure. This movement sets off a chain reaction governed by basic principles of fluid mechanics—specifically, Bernoulli’s principle and the stack effect.

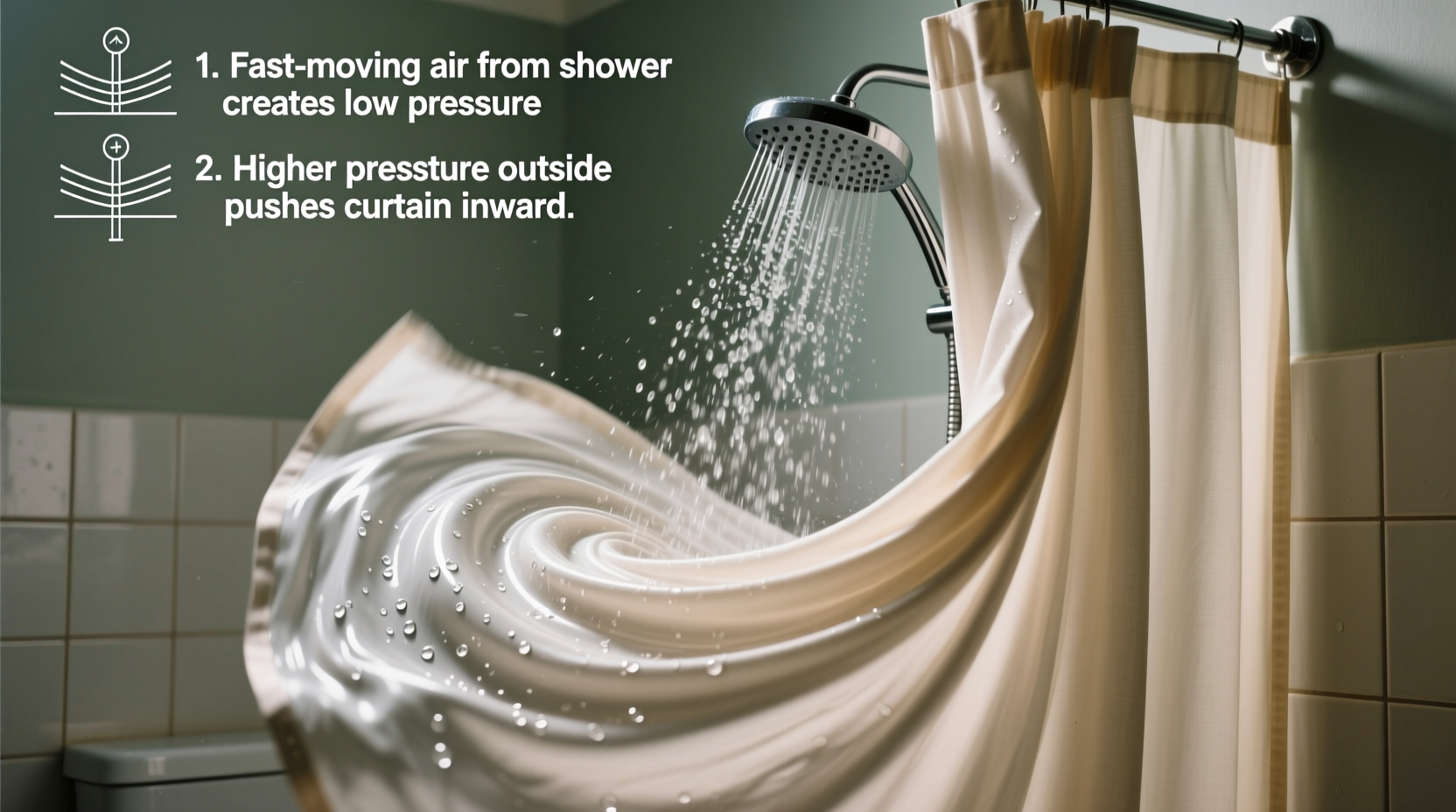

Bernoulli’s principle states that an increase in the speed of a fluid (including air) occurs simultaneously with a decrease in pressure. In your bathroom, the fast-moving steam and spray from the showerhead accelerate the air inside the shower area. As this air moves faster, its pressure drops relative to the stiller, higher-pressure air outside the curtain.

This imbalance creates a net force pushing the lightweight curtain inward—from high pressure to low pressure—just like wind pushing a sail.

Bernoulli’s Principle in Your Bathroom

Daniel Bernoulli, an 18th-century Swiss physicist, discovered that within a flowing fluid, regions with higher velocity have lower pressure. While he was studying liquids in pipes, his principle applies equally to gases like air—especially when they're moving quickly.

In the context of your shower, the spray from the nozzle breaks water into fine droplets and agitates the surrounding air. This turbulent mix shoots downward and circulates, creating a vertical current. As the air flows along the inside of the curtain, its speed increases, causing pressure to drop inside the shower stall.

Outside the curtain, the air remains relatively calm and maintains normal atmospheric pressure. Since nature seeks equilibrium, the higher-pressure air outside pushes the flexible curtain inward—toward the lower-pressure zone.

This phenomenon is similar to how airplane wings generate lift. On an aircraft, fast-moving air over the curved top surface creates lower pressure, while slower air beneath produces higher pressure, resulting in upward force. In your shower, the same imbalance pulls the curtain inward instead of lifting it up.

The Role of Temperature and Convection

Hot showers intensify the effect. Warm air rises due to convection—the process where heated fluids become less dense and move upward. Inside the shower, rising hot air creates a vertical draft that further accelerates airflow along the curtain’s inner surface.

This upward movement enhances the low-pressure zone near the center of the shower, increasing the inward pull on the curtain. Cold showers produce less of this effect because there’s minimal temperature difference between the inside and outside air, reducing convection currents.

“Even small differences in airspeed can generate enough pressure differential to move lightweight materials like plastic curtains.” — Dr. Lena Patel, Fluid Dynamics Researcher, MIT

The Stack Effect: Hot Air Rises, Pulling the Curtain Up and In

Beyond Bernoulli’s principle, another factor contributes: the stack effect. Also known as the chimney effect, this describes how warm air rises and escapes through upper openings, drawing cooler air in from below.

In your bathroom, hot air generated by the shower rises toward the ceiling. If your bathroom has vents or gaps near the top, that warm air escapes, creating a slight vacuum at floor level. To compensate, cooler air from outside the shower is drawn in—often entering under the curtain.

This inflow pushes against the bottom edge of the curtain, contributing to the ballooning effect. However, because the upper part of the curtain is more exposed to fast-moving air (and thus lower pressure), the net result is still a strong inward pull across most of its surface.

The combination of rising heat and lateral airflow means the curtain doesn’t just move inward—it often flutters unpredictably, responding to shifting currents within the confined space.

Solutions That Work: Applying Physics to Fix the Problem

Knowing the science is useful, but solving the problem requires practical adjustments. Some popular fixes work better than others, depending on which aspect of fluid dynamics you’re addressing.

1. Use a Weighted or Magnetic Curtain Liner

Heavy-duty liners with built-in weights or magnetic hemlines stick to the bathtub, resisting the initial pull caused by pressure differences. While they won’t stop airflow entirely, they anchor the lower portion so it doesn’t flap inward easily.

2. Install a Curved Shower Rod

A straight rod keeps the curtain close to your body. A curved rod extends outward, giving the curtain room to bow inward without touching you. This doesn’t eliminate the pressure differential but minimizes discomfort and splashback.

3. Improve Ventilation Strategically

Exhaust fans reduce humidity and remove rising hot air before it builds up significant convection currents. But placement matters: if the fan is too close to the shower, it may enhance the low-pressure zone inside, worsening the curtain movement. Running the fan *before* and *after* your shower helps stabilize air conditions without disrupting the flow mid-shower.

4. Leave the Bathroom Door Slightly Open

Closing the door tightly traps air and amplifies pressure imbalances. Allowing outside air to enter slowly through a cracked door equalizes pressure and reduces the force pushing the curtain inward.

Do’s and Don’ts: What Actually Helps (and What Doesn’t)

| Action | Effectiveness | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Use a curved shower rod | High | Creates physical buffer; allows curtain to move without touching user |

| Add weights or magnets to liner | High | Anchors curtain to tub, counteracts low-pressure lift at bottom |

| Run exhaust fan during shower | Moderate (can backfire) | May worsen pressure drop if poorly positioned |

| Crack the bathroom door open | High | Equalizes pressure between rooms |

| Tape curtain edges to wall | Low | Damage risk; ineffective against central bulge |

| Switch to glass doors | Very High | Eliminates flexible barrier entirely |

Mini Case Study: Solving the Problem in a Shared Apartment

Consider Sarah, who shares a small apartment bathroom with two roommates. Every morning, someone complains about the “haunted” shower curtain attacking them. They tried doubling up liners, using suction cups, and even hanging clothespins on the edges—all failed.

After reading about the physics involved, Sarah implemented three changes: she replaced the straight rod with a curved one, switched to a liner with magnetic weights, and started leaving the bathroom door ajar during showers. Within a week, complaints stopped.

The solution wasn’t one fix alone but a layered approach addressing both pressure imbalance and physical constraints. The curved rod gave space, the weights held the bottom, and the open door prevented pressure buildup. It wasn’t magic—just applied science.

Step-by-Step Guide to Stop the Inward Blow

- Assess your current setup. Note whether you use a straight or curved rod, what type of liner you have, and how well-ventilated the bathroom is.

- Upgrade to a weighted or magnetic liner. These are inexpensive and easy to install, providing immediate resistance to inward motion.

- Replace your shower rod with a curved model. Most standard tubs accommodate these without modification. Installation takes under 15 minutes.

- Adjust ventilation habits. Run the exhaust fan for 10 minutes before and after your shower, not during, unless the fan is ceiling-mounted away from the stall.

- Leave the bathroom door slightly open. Even a 2-inch gap allows enough air exchange to balance pressure.

- Test and observe. Try one change at a time to see what makes the biggest difference in your specific environment.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does water temperature really affect curtain movement?

Yes. Hot water produces steam and heats the air inside the shower, increasing convection currents and enhancing the low-pressure zone. Cold showers generate far less air movement and rarely cause noticeable curtain suction.

Will a shower door solve the problem completely?

Almost entirely. Glass or solid-panel doors eliminate the flexible barrier that responds to pressure changes. They also contain water better and require less maintenance than fabric or plastic curtains.

Are some shower curtain materials better than others?

Heavier materials like vinyl or PEVA resist movement better than thin plastic. Textured or ribbed designs may also disrupt airflow slightly, reducing the smoothness of air travel along the surface—which can minimize the Bernoulli effect.

Conclusion: Master the Science, Reclaim Your Shower

The shower curtain that mysteriously attacks your ankles isn’t broken—it’s obeying the laws of physics. From Bernoulli’s principle to thermal convection, multiple fluid dynamic forces combine to create the inward billow we all know too well. But once you understand the mechanisms, you gain control. Simple changes—like adding weight, adjusting airflow, or reshaping your shower space—can neutralize these invisible forces.

This isn’t just about comfort; it’s about designing smarter daily routines based on real science. Whether you live in a historic building with weak ventilation or a modern home with sleek fixtures, the principles remain the same. Apply them wisely, and you’ll never dread the fluttering curtain again.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?