Snake owners often experience concern when their reptile refuses a meal. While feeding strikes are common in snakes, persistent refusal can signal underlying health issues or environmental stress. Unlike mammals, snakes have evolved to survive extended fasts, which can make it difficult to determine whether a skipped meal is part of natural behavior or a symptom of distress. Understanding the difference between normal fasting patterns and stress-related appetite loss is essential for responsible snake care.

This article explores the biological, environmental, and psychological factors behind feeding refusal in pet snakes. You’ll learn how to interpret behavioral cues, assess habitat conditions, and take proactive steps to support your snake’s well-being. Whether you're caring for a ball python, corn snake, or king snake, this guide offers actionable insights grounded in herpetological best practices.

Biological Reasons Snakes Skip Meals

Before assuming something is wrong, it's important to recognize that many snakes naturally go through periods of reduced or no feeding. These behaviors are often tied to seasonal changes, reproductive cycles, or growth stages.

In the wild, snakes adjust their feeding frequency based on prey availability and energy demands. Captive snakes retain these instincts. For example:

- Ball pythons commonly undergo \"balling up\" and stop eating during cooler months, mimicking brumation patterns.

- Corn snakes may reduce feeding in fall and winter even without temperature drops.

- Molting cycles almost universally cause temporary anorexia. Snakes typically stop eating 5–7 days before shedding due to impaired vision and increased vulnerability.

Growth rate also influences appetite. Juvenile snakes eat more frequently—often weekly—while adults may only need food every 10–14 days or longer. A mature boa constrictor might eat just once a month and remain healthy.

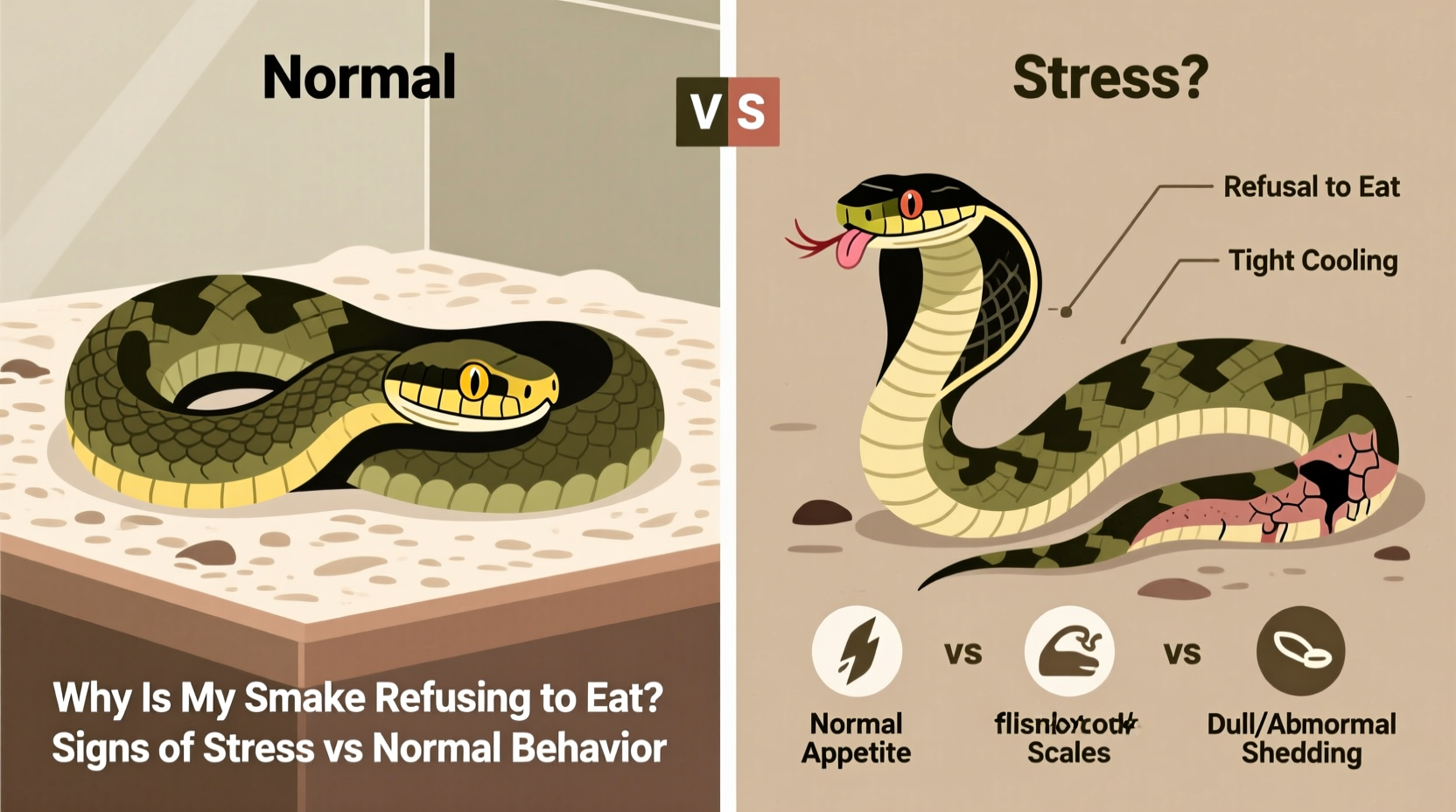

Common Signs of Stress in Captive Snakes

When a snake stops eating, stress is one of the most frequent culprits. Unlike natural fasting, stress-induced anorexia often comes with other observable symptoms. Recognizing these signs early can prevent long-term health decline.

Stress in snakes arises from improper husbandry, overhandling, or environmental disturbances. Key indicators include:

- Constant hiding or refusal to leave shelter

- Frequent attempts to escape (pacing, nose rubbing on enclosure walls)

- Aggressive behavior such as hissing or striking when approached

- Lethargy outside of molting or digestion periods

- Regurgitation of meals shortly after eating

- Weight loss, sunken eyes, or muscle atrophy over time

Environmental stressors are especially prevalent in newly acquired snakes. It’s not unusual for a snake to refuse food for weeks after being brought home. This adjustment period is normal, but should not exceed 6–8 weeks without veterinary evaluation.

“Many feeding issues in captive snakes stem from mismatched environments, not medical problems. Stability and consistency are key.” — Dr. Melissa Kaplan, Reptile Welfare Researcher

Distinguishing Normal Behavior from Problematic Refusal

Telling the difference between a healthy fast and a concerning refusal requires attention to context. The following table outlines key distinctions:

| Factor | Normal Fasting | Stress or Illness |

|---|---|---|

| Duration | Up to several weeks; seasonal | Prolonged beyond 2–3 months |

| Body Condition | Healthy weight, firm musculature | Noticeable weight loss, spine prominence |

| Behavior | Alert, explores occasionally | Lethargic, hides constantly |

| Molting Cycle | Refusal aligns with pre-shed phase | No upcoming shed, yet still refusing |

| Defecation | Regular bowel movements | Constipation or diarrhea |

| Hydration | Clear eyes, smooth skin | Dull eyes, retained shed, wrinkled skin |

A snake that remains active, maintains hydration, and shows no physical deterioration is likely engaging in species-typical behavior. However, if weight loss occurs or the snake becomes unresponsive, intervention is necessary.

Step-by-Step Guide to Addressing Feeding Refusal

If your snake has stopped eating and you suspect stress or illness, follow this structured approach to diagnose and resolve the issue:

- Assess Husbandry Conditions

Check temperature gradients (warm side 85–90°F, cool side 75–80°F), humidity levels (varies by species—ball pythons need 50–60%, some colubrids require less), and enclosure size. Ensure there are at least two secure hides and a water bowl large enough for soaking. - Review Recent Changes

Did you change substrates, move the enclosure, introduce new pets, or increase handling? Even subtle disruptions can trigger stress responses. Return to previous stable conditions if possible. - Try Prey Variations

Offer different prey types (e.g., switch from mouse to rat pup, or use chicks for kingsnakes). Warm prey to body temperature and consider scent transfer—rubbing prey with lizard or bird feathers may stimulate interest. - Adjust Feeding Method

Feed in a separate, quiet container to minimize distractions. Some snakes prefer live prey (though controversial), while others respond better to tongs or pre-killed options. Never force-feed unless advised by a vet. - Monitor for Medical Issues

Look for nasal discharge, open-mouth breathing, lumps, or abnormal feces. Internal parasites, respiratory infections, or mouth rot can suppress appetite. If symptoms persist beyond four weeks, consult an exotic veterinarian. - Implement a Feeding Schedule Reset

Suspend feeding for 7–10 days to allow full digestion, then reintroduce prey under optimal conditions. Patience is critical—forcing food can worsen aversion.

Real Case: Resolving Chronic Anorexia in a Ball Python

Jamie adopted a young female ball python from a local breeder. The snake ate well initially but stopped accepting food after three months. Despite offering pinky mice and fuzzy rats, she consistently refused meals for nine weeks. Concerned about dehydration and weight loss, Jamie consulted a reptile-specialized vet.

The vet reviewed photos of the enclosure and discovered the warm-side basking spot was only 78°F—below the required threshold. Humidity was also low at 40%. After adjusting the heat gradient using an under-tank heater and adding a moisture-retaining substrate, Jamie introduced a larger hide box with damp sphagnum moss.

Two weeks later, the snake completed a successful shed. Within days, she accepted a defrosted fuzzy rat offered via feeding tongs in a darkened secondary container. Over the next six months, consistent feeding resumed, and the snake regained lost weight.

This case illustrates how seemingly minor environmental flaws can significantly impact feeding behavior. Correcting thermal regulation alone resolved what appeared to be a complex refusal issue.

Essential Do’s and Don’ts When Your Snake Won’t Eat

To avoid worsening the situation, follow this checklist of recommended actions and common mistakes:

| Do’s | Don’ts |

|---|---|

| ✔ Maintain proper temperature and humidity | ✖ Overhandle during fasting periods |

| ✔ Keep a detailed feeding and shedding log | ✖ Offer food too frequently (every few days) |

| ✔ Provide secure hiding spots on both ends | ✖ Mix multiple stressors (new cage + new food) |

| ✔ Try scent transfer or warming prey | ✖ Leave live prey unattended (risk of injury) |

| ✔ Consult a vet if refusal exceeds 3 months | ✖ Force-feed without professional guidance |

Frequently Asked Questions

How long can a healthy snake go without eating?

Adult snakes can safely fast for 2–3 months depending on age, species, and body condition. Juveniles should not go longer than 3–4 weeks without food. Weight monitoring is crucial—if a snake loses more than 10% of its starting mass, veterinary assessment is needed.

Is it normal for my snake to spit up food?

Regurgitation is not normal and indicates a problem. Common causes include handling too soon after feeding, incorrect temperatures impairing digestion, or stress. If regurgitation occurs more than once, seek veterinary advice to rule out infection or gastrointestinal disease.

Should I feed live or frozen-thawed prey?

Frozen-thawed prey is generally safer and more humane. Live rodents can injure snakes, especially if left unsupervised. Most captive-bred snakes readily accept properly warmed frozen prey. If transitioning, try wiggling the prey with tongs to simulate movement.

Conclusion: Proactive Care Prevents Long-Term Issues

A snake refusing food isn’t always a crisis, but it should never be ignored indefinitely. By understanding the line between instinctual fasting and stress-induced anorexia, keepers can provide timely, effective care. The key lies in observation, consistency, and respect for your snake’s natural rhythms.

Start today by auditing your enclosure setup, reviewing your feeding logs, and eliminating potential stressors. Small adjustments often yield dramatic improvements. When in doubt, partner with a qualified reptile veterinarian—early intervention prevents complications.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?