Sourdough baking is both an art and a science. When done right, it produces loaves with complex flavor, an open crumb, and a satisfying chew. But when the result is a brick-like loaf that barely rises, frustration sets in quickly. A dense sourdough bread is one of the most common complaints among home bakers—and more often than not, the root cause lies with the starter.

Your sourdough starter is a living culture of wild yeast and lactic acid bacteria. It’s responsible for leavening your dough and developing flavor. If it's underperforming, no amount of perfect shaping or precise oven spring will save your loaf. Understanding how to diagnose and correct issues with your starter is essential to achieving that light, airy texture you’re aiming for.

The Role of the Starter in Sourdough Bread Structure

A healthy sourdough starter produces carbon dioxide gas during fermentation, which gets trapped in the gluten network of the dough, causing it to rise. The strength of this rise depends on two key factors: the vitality of the yeast and the development of gluten in the dough.

If your starter isn’t strong enough, it won’t produce sufficient gas. Even if gluten structure is well-developed, without adequate leavening power, the bread collapses or fails to expand in the oven. Conversely, a strong starter can't compensate for poor dough handling—but it’s the foundation of success.

“Your starter is the heartbeat of your sourdough. No matter how skilled you are at shaping or steaming, if the starter isn’t active, the loaf won’t rise.” — Dr. Karl DeSiel, Fermentation Scientist, University of California

Common Signs of a Weak or Unhealthy Starter

Before blaming your technique, assess your starter’s health. A truly active starter should double in size within 4–8 hours of feeding, have a bubbly surface, and emit a pleasantly tangy, fruity aroma—not just sharp vinegar or rotten notes.

- Lack of rise: Fails to double after feeding, even after 12 hours.

- Foul odor: Smells like acetone, nail polish remover, or sewage instead of yogurt or ripe fruit.

- Stiff or gluey texture: Doesn’t flow or show visible bubbles throughout.

- Hooch formation: A layer of dark liquid (alcohol byproduct) forms frequently, indicating starvation.

- Inconsistent performance: Works one day but fails the next with no change in routine.

Step-by-Step Guide to Reviving a Struggling Starter

If your starter shows signs of weakness, don’t discard it immediately. Most starters can be revived with consistent care. Follow this timeline over 3–5 days to restore its strength:

- Day 1: Discard all but 25g of starter. Feed with 50g all-purpose flour and 50g lukewarm water (75–80°F / 24–27°C). Cover loosely and leave at warm room temperature (75–80°F).

- Day 2: Repeat the same feeding every 12 hours. Observe for small bubbles forming around the edges after 6–8 hours.

- Day 3: Switch to whole grain flour (rye or whole wheat) for one feeding. These flours contain more nutrients and microbes to boost microbial activity.

- Day 4: Return to all-purpose flour. If doubling within 6–8 hours, proceed to test bake. If not, continue feeding twice daily.

- Day 5: Perform a float test: Place a teaspoon of starter in a glass of room-temperature water. If it floats, it’s ready to use.

This process resets the pH balance, replenishes food sources, and encourages a balanced yeast-to-bacteria ratio. Patience is key—rushing into baking with an unready starter leads to disappointment.

Environmental and Feeding Factors That Impact Starter Health

Even with regular feedings, environmental conditions play a major role in starter performance. Temperature, hydration, flour type, and feeding frequency all influence microbial balance.

| Factor | Optimal Condition | Pitfalls to Avoid |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 75–80°F (24–27°C) | Cold kitchens slow fermentation; overheating kills microbes |

| Flour Type | All-purpose or whole rye for refreshments | Bleached flour or low-protein flours weaken microbial growth |

| Hydration | 100% (equal flour and water by weight) | Too dry = sluggish; too wet = unstable structure |

| Feeding Frequency | Every 12 hours if kept at room temp | Infrequent feeding leads to hooch and acidity buildup |

| Water Quality | Filtered or bottled (chlorine-free) | Chlorinated tap water inhibits microbial activity |

Many bakers overlook water quality. Municipal tap water often contains chlorine or chloramines, which are designed to kill microbes—including those in your starter. Using filtered or boiled-and-cooled water can make a noticeable difference in starter vigor.

Real Example: Sarah’s Comeback Starter

Sarah, a home baker in Portland, struggled for months with dense sourdough. Her starter looked inert—minimal bubbles, frequent hooch, and a sour smell. She fed it daily with bleached all-purpose flour and tap water, storing it on a cool countertop.

After switching to filtered water, feeding with organic whole wheat flour twice daily, and placing her jar on a heating mat set to 78°F, she noticed improvement within 48 hours. By day four, her starter doubled consistently and passed the float test. Her next loaf had a dramatically improved rise and open crumb.

She later shared: “I thought I was doing everything right, but I didn’t realize how much chlorine and cold temps were holding my starter back. Changing two things made all the difference.”

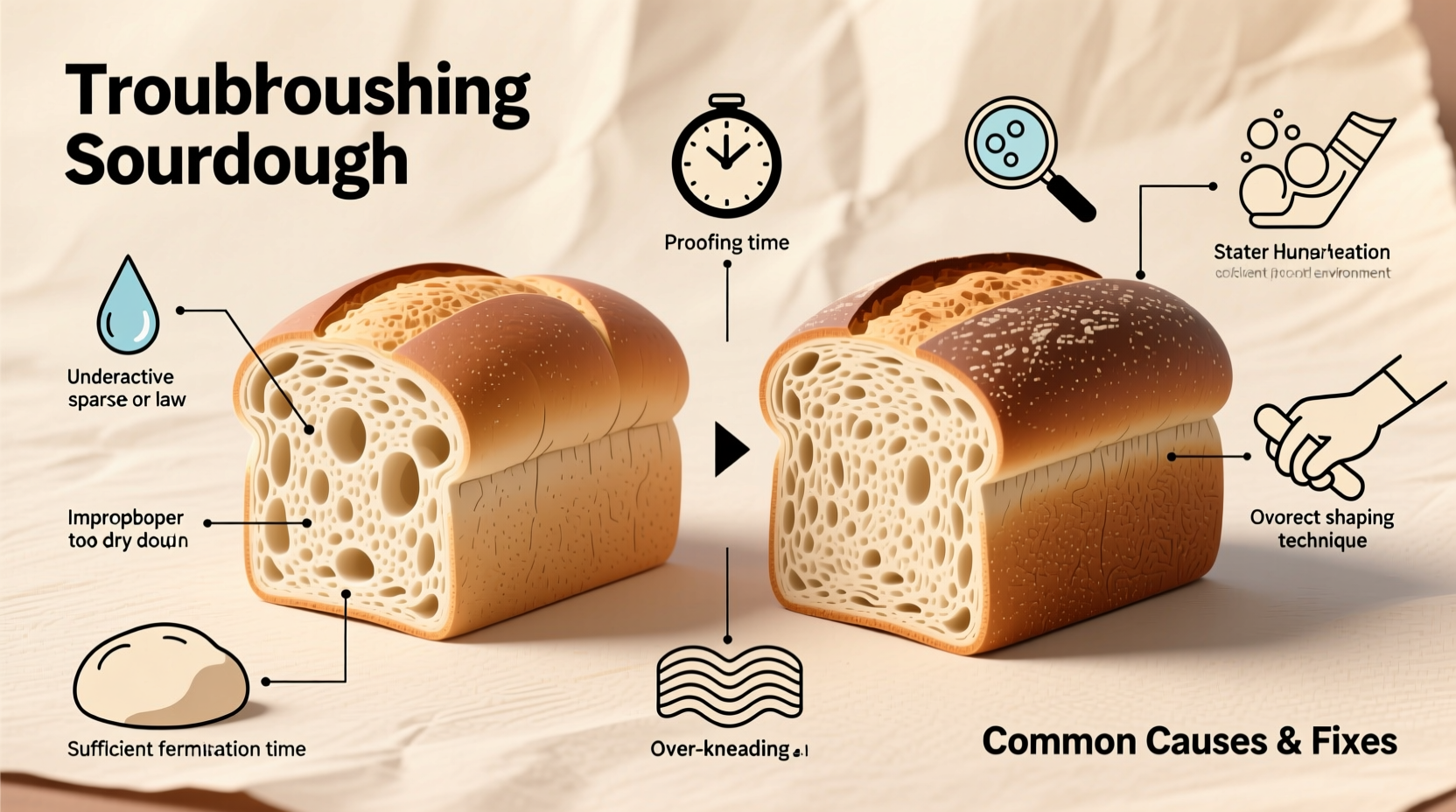

Troubleshooting Dense Bread Beyond the Starter

While the starter is often the culprit, other factors contribute to density. Even with a strong starter, poor technique can ruin a loaf.

Underproofing vs. Overproofing

Underproofed dough hasn’t fermented long enough to develop gas and flavor. It bakes up tight and gummy. Overproofed dough has exhausted its gas-producing capacity and collapses during baking, also resulting in density.

To test readiness, perform the \"poke test\": Gently press the dough with a fingertip. If it springs back slowly and leaves a slight indentation, it’s ready. If it snaps back immediately, it needs more time. If it doesn’t spring back at all, it’s overproofed.

Gluten Development

Inadequate gluten development prevents the dough from trapping gas effectively. This happens when there’s insufficient kneading, mixing, or coil folds during bulk fermentation.

For high-hydration doughs, perform 3–4 sets of coil folds spaced 30 minutes apart during the first two hours of bulk fermentation. This builds strength without overworking the dough.

Baking Technique

Dense crumb can also stem from low oven temperature, lack of steam, or improper scoring. Steam keeps the crust flexible during the first phase of baking, allowing maximum oven spring. Without it, the loaf cracks unpredictably and fails to expand.

Checklist: Is Your Starter Ready to Bake?

Use this checklist before mixing your dough to avoid another dense loaf:

- ✅ Doubles in size within 6–8 hours of feeding

- ✅ Has visible bubbles throughout, not just on top

- ✅ Smells pleasantly tangy, fruity, or yogurty (not alcoholic or putrid)

- ✅ Passes the float test (a spoonful floats in room-temp water)

- ✅ Fed within the last 8–12 hours with fresh flour and water

- ✅ Stored and fed at optimal temperature (75–80°F)

- ✅ Uses non-chlorinated water and unbleached flour

If any of these items fail, delay baking and continue feeding until all criteria are met.

FAQ: Common Questions About Dense Sourdough and Starter Issues

Can I use my starter straight from the fridge?

It’s possible, but not ideal. Cold-stored starters are sluggish and acidic. For best results, take 25g of refrigerated starter, feed it at room temperature, and wait until it doubles and passes the float test before baking. This usually takes 8–12 hours.

Why does my bread rise in the oven but collapse as it cools?

This typically indicates overproofing or weak gluten structure. The loaf expands initially due to oven spring but lacks internal strength to hold its shape. Strengthen your dough with more coil folds and shorten final proofing time.

How often should I feed a starter kept at room temperature?

Twice daily, every 12 hours, if you plan to bake regularly. If not in use, store it in the refrigerator and feed once a week. Always bring it back to room temperature and refresh 1–2 times before baking.

Conclusion: Building Confidence Through Consistency

Dense sourdough bread doesn’t mean failure—it means feedback. Your loaf is telling you something about your starter, your environment, or your process. More often than not, reviving a sluggish starter through proper feeding, temperature control, and clean ingredients transforms future results.

Baking with wild yeast requires patience and observation. Each adjustment teaches you more about the living ecosystem you're nurturing. Don’t give up after one dense loaf. Instead, refine your approach, track changes, and trust the process.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?