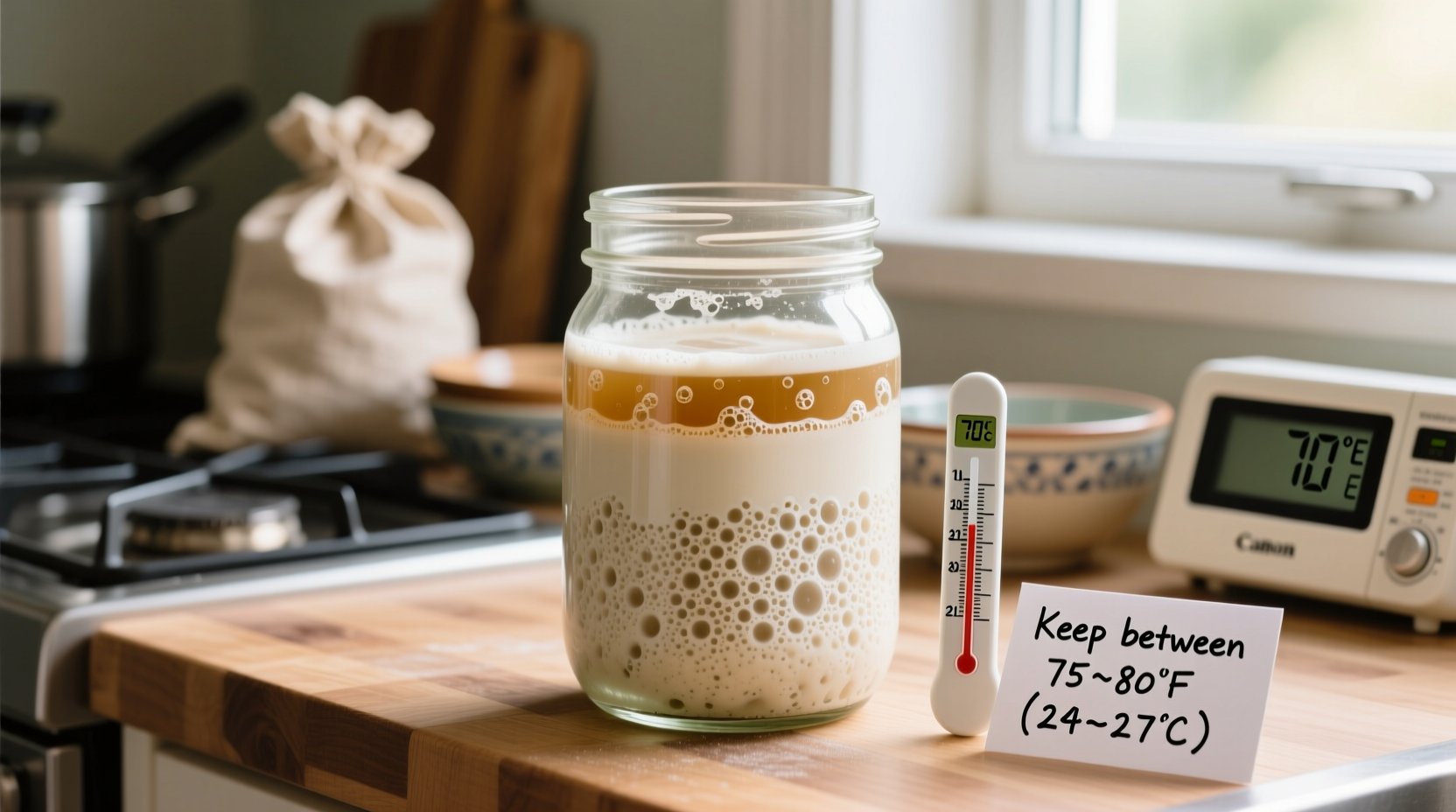

A healthy sourdough starter should bubble vigorously and rise significantly within 4–8 hours after feeding. When it doesn’t, it’s natural to feel frustrated—especially if you’ve been consistent with feedings. The most common culprit? Temperature. But other factors like flour choice, hydration, and microbial health also play key roles. Understanding the science behind fermentation and how environmental conditions affect your starter is essential to diagnosing and fixing the issue.

This guide breaks down the reasons your starter may not be rising, with a focus on temperature-related problems, and provides actionable steps to revive and maintain a strong, active culture.

The Role of Temperature in Sourdough Fermentation

Sourdough starters rely on wild yeast and lactic acid bacteria to ferment flour and produce gas, which causes the starter to rise. These microorganisms are highly sensitive to temperature. Too cold, and they slow down or become dormant; too hot, and they die off. The ideal range for balanced activity is between 70°F and 78°F (21°C–26°C).

At cooler temperatures—below 65°F (18°C)—yeast and bacteria metabolize slowly. You might see minimal bubbles and little to no volume increase. Conversely, above 85°F (29°C), the environment becomes stressful. Acetic acid bacteria dominate, creating a sharp vinegar smell, while beneficial yeasts begin to weaken. Prolonged exposure above 90°F (32°C) can kill the culture entirely.

Finding the Sweet Spot: Optimal Ranges by Microbe Type

| Microorganism | Optimal Temp Range (°F) | Effect Outside Range |

|---|---|---|

| Wild Yeast (Saccharomyces exiguus) | 70–78°F | Below 65°F: Dormant; Above 85°F: Stressed or dies |

| Lactic Acid Bacteria (Lactobacillus spp.) | 75–85°F | Below 60°F: Slow; Above 90°F: Overproduction of acid |

| Acetic Acid Bacteria | 68–77°F | Thrives in cooler, aerobic conditions—can overpower if yeast lags |

Maintaining a stable temperature within this narrow window encourages balanced fermentation, predictable rise times, and a pleasant aroma. Fluctuations—even daily swings—can disrupt microbial harmony and delay peak activity.

Common Causes of Poor Rise After Feeding

While temperature is often the primary factor, several interrelated elements can prevent your starter from rising properly. Addressing them systematically increases your chances of revival.

1. Inconsistent or Suboptimal Ambient Temperature

If your kitchen averages below 68°F, especially at night, your starter may take 12 hours or more to peak—or not rise at all. This is particularly common in basements, garages, or poorly insulated spaces during colder months.

Conversely, placing your starter near a heat source (oven, radiator, dishwasher) can create localized hot spots that damage microbes even if the room feels cool.

2. Incorrect Flour Type or Quality

Not all flours support robust fermentation. Bleached white flour lacks nutrients and enzymes needed for microbial growth. Whole grain flours (rye, whole wheat) provide more food but can cause faster acid buildup, which may inhibit yeast over time if not managed.

Freshness matters. Old or stale flour loses enzymatic activity and may harbor mold spores that compete with your culture.

3. Imbalanced Hydration

Most starters thrive at 100% hydration (equal parts water and flour by weight). Too much water (125%+) creates a runny consistency that prevents structural rise. Too little (below 80%) restricts microbial mobility and gas retention.

4. Infrequent or Irregular Feedings

Going more than 48 hours without feeding—especially at room temperature—allows acidity to build up to inhibitory levels. The culture becomes too acidic for yeast to reproduce effectively, leading to sluggishness or stagnation.

5. Chlorinated Water

Tap water treated with chlorine or chloramine can harm delicate microbes. While small amounts may not kill a mature starter, they can suppress activity in younger or weakened cultures.

Step-by-Step Revival Plan for a Lethargic Starter

If your starter shows no rise after feeding, follow this structured approach to diagnose and correct the problem. Allow 3–5 days for full recovery, depending on severity.

- Assess current condition: Check for signs of life—bubbles, domed surface, pleasant sour aroma. If there’s mold, pink/orange streaks, or foul odor, discard and restart.

- Move to a warmer spot: Aim for 72–76°F. Use a proofing box, oven with light on, or place near—but not on—a radiator.

- Discard 80% of the starter: Reduce acidity and refresh with equal parts (by weight) unbleached bread flour and lukewarm water (80°F).

- Feed twice daily: Every 12 hours, maintaining 1:2:2 ratio (starter:flour:water). For example, 20g starter + 40g flour + 40g water.

- Cover loosely: Use a breathable lid or cloth to allow CO₂ escape while preventing contamination.

- Monitor closely: Look for doubling in volume within 6–8 hours. If not rising, increase temperature slightly or switch to rye flour for one feeding to boost microbial activity.

- Test floatability: Once bubbly and doubled, place a spoonful in room-temp water. If it floats, it’s ready to bake with.

Patience is critical. A severely weakened starter may take multiple feedings before regaining strength. Avoid discarding too early—many starters recover after three consecutive warm, well-fed cycles.

Real-World Example: Recovering a Winter-Weakened Starter

Sarah, a home baker in Vermont, noticed her once-reliable starter stopped rising after she moved it to a drafty corner of her kitchen in December. Despite daily feedings, it remained flat and developed a layer of hooch (liquid alcohol) every 12 hours.

She measured the ambient temperature and found it averaged 62°F overnight. Following advice from a local baking group, she placed the jar on a heating mat set to 75°F, covered with a towel. She switched to twice-daily feedings using rye flour for the first two cycles, then returned to bread flour.

By day three, the starter was bubbling within 4 hours and doubled in size by 7 hours. On day four, it passed the float test and produced a successful loaf of sourdough boule. The key? Consistent warmth and nutrient-rich feedings.

“Temperature stability is more important than frequency of feeding. A cold starter, no matter how well-fed, simply won’t perform.” — Dr. Carl Harris, Microbiologist & Artisan Bread Researcher

Do’s and Don’ts for Maintaining a Healthy Starter

| Do’s | Don’ts |

|---|---|

| Keep starter in a warm, draft-free spot (70–78°F) | Leave it near windows, AC units, or exterior doors |

| Use unbleached, high-quality flour | Use self-rising or bleached all-purpose flour |

| Feed regularly—every 12 hours at room temp | Go more than 48 hours without feeding (unless refrigerated) |

| Stir down before each feeding to incorporate oxygen | Seal tightly in an airtight container |

| Record feeding times and rise observations | Expect identical behavior every day—natural variation occurs |

Frequently Asked Questions

How long should I wait before worrying if my starter isn’t rising?

If your starter shows no bubbles or expansion within 8–12 hours of feeding at room temperature, it’s worth investigating. At cooler temps (below 70°F), extend the window to 16–24 hours before concern. Immediate red flags include gray color, black specks, or rotten smell—discard if present.

Can I use my oven to keep my starter warm?

Yes, but carefully. Turn on the oven light only (no heat), place the starter inside, and monitor temperature with a thermometer. Avoid using pilot lights or residual heat from recent baking, as these can exceed safe limits. Never leave the oven on continuously for this purpose due to safety risks.

Is it normal for my starter to rise slowly after being refrigerated?

Yes. Cold slows microbial metabolism dramatically. After removing from the fridge, expect 24–48 hours of sluggish activity before full vigor returns. Perform 2–3 consecutive room-temperature feedings spaced 12 hours apart to reactivate it.

Final Checklist: Troubleshooting Flowchart

- ✅ Is the ambient temperature between 70–78°F?

- ✅ Are you using unbleached, fresh flour?

- ✅ Is your water free of chlorine?

- ✅ Have you fed the starter within the last 12–24 hours?

- ✅ Is the container clean and non-reactive (glass, ceramic)?

- ✅ Is the lid loose enough to allow gas release?

- ✅ Have you stirred the starter before assessing rise?

- ✅ Does it smell tangy, not putrid or alcoholic?

If all answers are “yes” and still no rise, try one feeding with whole rye flour—it’s rich in nutrients and often jumpstarts dormant cultures. Then return to regular feeding routine.

Conclusion: Consistency and Environment Are Key

A sourdough starter is a living ecosystem, not a static ingredient. Its performance reflects the conditions you provide. When it fails to rise after feeding, temperature is usually the silent saboteur. By stabilizing the environment, refining your feeding technique, and understanding microbial rhythms, you can restore vitality to even the most sluggish starter.

Don’t rush the process. Trust the timeline, keep records, and make small, deliberate adjustments. Soon, you’ll see predictable bubbles, steady rise, and the satisfying jiggle of a healthy, active culture ready for baking.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?