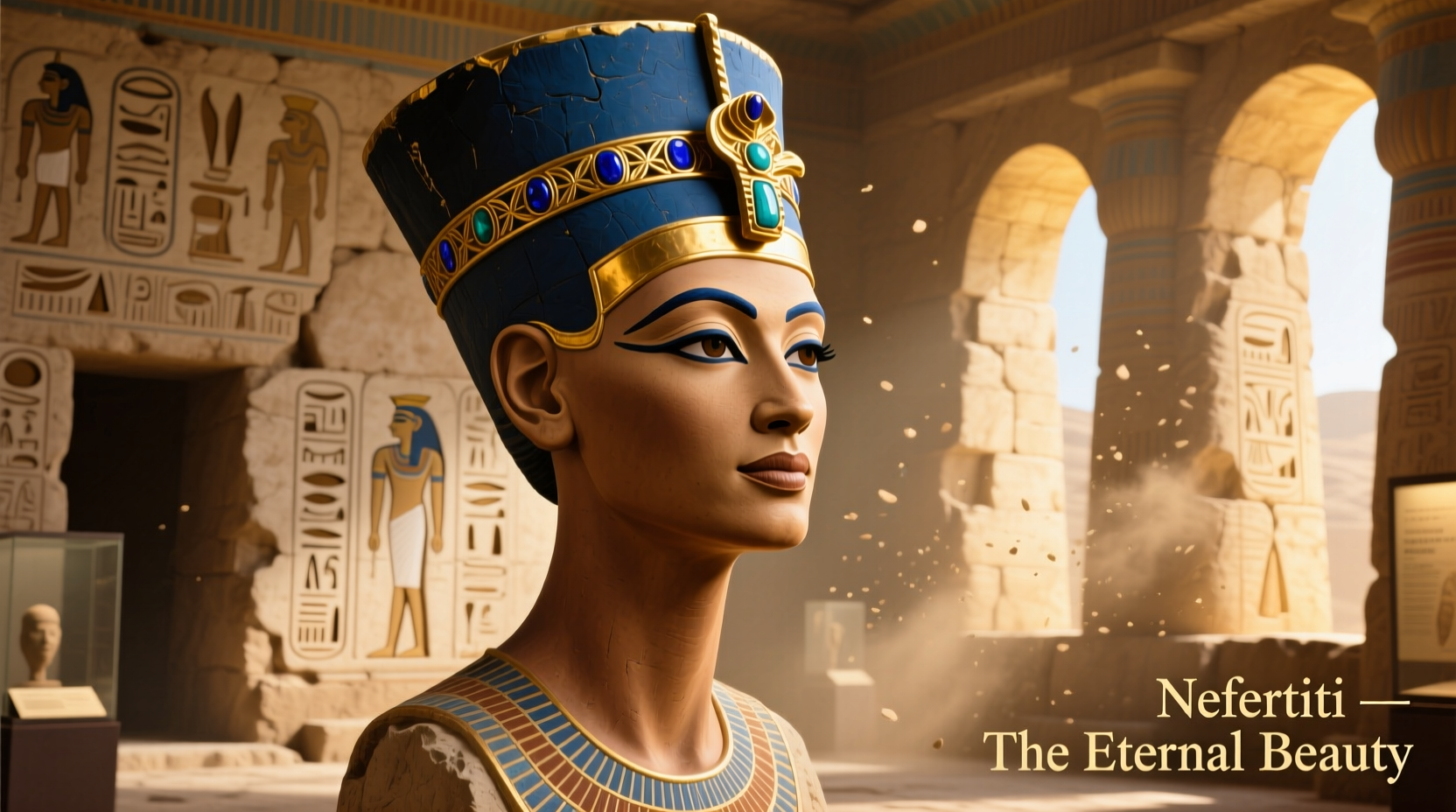

More than three millennia after her time, Queen Nefertiti remains one of the most recognizable figures from ancient Egypt. Her striking bust, discovered in 1912, has become a global symbol of beauty, power, and mystery. Yet, her fame extends far beyond aesthetics. Nefertiti was not merely a royal consort; she was a central figure in one of the most radical religious and cultural transformations in Egyptian history. Her role in the Amarna Revolution, her unprecedented visibility in art and politics, and the enigma surrounding her disappearance have cemented her place in both historical scholarship and popular imagination.

The Rise of a Revolutionary Queen

Nefertiti rose to prominence during the 18th Dynasty of ancient Egypt, around 1350 BCE, as the Great Royal Wife of Pharaoh Akhenaten. At a time when Egypt worshipped a pantheon of gods, Akhenaten initiated a dramatic shift by promoting Aten, the sun disk, as the sole deity. This monotheistic experiment marked a sharp departure from centuries of polytheistic tradition. Nefertiti wasn’t just a passive observer—she played an active role in this spiritual revolution.

Artistic depictions from the period show her participating in religious rituals alongside Akhenaten, sometimes even performing rites typically reserved for pharaohs. In the boundary stelae of Amarna, she is depicted smiting enemies, a symbolic act usually associated with kingship. These images suggest that Nefertiti may have held co-regent status or wielded significant authority within the new capital city of Akhetaten (modern-day Amarna).

“Nefertiti was more than a queen—she was a theological partner in Akhenaten’s religious project. Her presence in divine scenes elevates her to near-pharaonic status.” — Dr. Kara Cooney, Egyptologist and author of *When Women Ruled the World*

The Power Behind the Bust: Art, Beauty, and Propaganda

No discussion of Nefertiti’s fame is complete without addressing her limestone bust, crafted by the court sculptor Thutmose around 1345 BCE. Discovered in his workshop at Amarna, the sculpture is renowned for its lifelike features, symmetry, and serene expression. The painted surface captures delicate details—the arched brows, elongated neck, and the distinctive blue crown now known as the “Nefertiti cap crown.”

While often celebrated for its aesthetic perfection, the bust served a deeper purpose. It was likely a model for official portraits used throughout the kingdom, functioning as a tool of political and religious propaganda. By idealizing Nefertiti’s image, the regime reinforced the divine aura of the royal family and their connection to Aten. Her beauty wasn’t incidental—it was ideological.

A Woman of Influence: Religious and Political Roles

Nefertiti’s influence extended into the core of state affairs. Inscriptions from Amarna reveal that she bore titles such as “Lady of All Women” and “Mistress of the Two Lands,” emphasizing her elevated status. More significantly, she was named “Neferneferuaten-Nefertiti,” linking her name directly to the Aten cult (“Beautiful are the Beauties of Aten”).

Evidence suggests she may have ruled independently after Akhenaten’s death. Some scholars argue that the shadowy co-regent or successor known as Neferneferuaten—listed in the king lists but with unclear gender—was Nefertiti herself assuming full pharaonic powers. This theory gains weight from the fact that no definitive burial or mummy has been conclusively tied to her, leaving room for speculation about her later years.

If true, this would place her among a rare group of female rulers in Egyptian history, including Hatshepsut and Cleopatra. Unlike them, however, Nefertiti vanished from records abruptly, adding to her mystique.

Timeline of Key Events in Nefertiti’s Life

- c. 1370 BCE: Believed birth in Egypt, possibly to a high-ranking official or foreign princess (exact parentage unknown).

- c. 1353 BCE: Marries Amenhotep IV, who later becomes Akhenaten.

- c. 1346 BCE: Moves with Akhenaten to new capital at Amarna; becomes central figure in Aten worship.

- c. 1341 BCE: Last confirmed depiction in Year 16 of Akhenaten’s reign; disappears from historical record.

- 1912 CE: Bust discovered by German archaeologist Ludwig Borchardt in Amarna workshop.

- 1923 CE: Bust displayed publicly in Berlin, sparking global fascination.

The Afterlife of a Queen: Cultural Legacy and Modern Impact

Nefertiti’s legacy transcends archaeology. She has become a cultural icon, symbolizing feminine power, elegance, and resistance to tradition. Her image has been reproduced in fashion, film, and political discourse. During the early 20th century, her bust was used in debates about racial identity and African heritage, with scholars and activists arguing that her features reflect indigenous North African traits rather than Near Eastern or European ones.

Today, Egypt continues to call for the repatriation of the bust, currently housed in Berlin’s Neues Museum. The dispute underscores broader conversations about colonial-era acquisitions and cultural ownership. For many Egyptians, Nefertiti is not just a historical figure—she is a national symbol whose rightful place is in Cairo.

“The Nefertiti bust isn’t just art—it’s a stolen piece of our identity. Returning it would be an act of historical justice.” — Zahi Hawass, former Egyptian Minister of Antiquities

Do’s and Don’ts When Understanding Nefertiti’s Historical Role

| Do | Don't |

|---|---|

| Recognize her active role in religious reform and governance. | Reduce her significance to her physical appearance alone. |

| Consider the political context of Amarna art and iconography. | Assume all depictions are literal representations of reality. |

| Explore the possibility of her ruling as a pharaoh under another name. | Treat gaps in the historical record as proof of insignificance. |

| Engage with modern debates about cultural heritage and repatriation. | Ignore the ethical dimensions of where her artifacts are displayed. |

Mini Case Study: The Discovery That Changed Everything

In December 1912, German archaeologist Ludwig Borchardt led an excavation team in Amarna. Among the finds in a buried studio was a painted limestone bust of a woman with astonishing realism. Borchardt recorded it in his diary as “a masterpiece… you cannot describe it, only see it.” Despite agreements that significant finds should be shared with the Egyptian government, the bust was shipped to Germany under contested circumstances. Initially downplayed as a mere plaster model, it was unveiled to the public in 1923 and instantly became a sensation. Museums reported spikes in attendance, and artists began reinterpreting her image. The discovery transformed Nefertiti from a forgotten queen into a global phenomenon—and ignited a century-long debate over cultural restitution.

Frequently Asked Questions

Was Nefertiti a pharaoh?

There is compelling evidence that she may have ruled as a co-regent or even sole ruler under the name Neferneferuaten after Akhenaten’s death. While not definitively proven, inscriptions and her prominent role in state rituals support this theory.

Why is Nefertiti’s bust in Germany and not Egypt?

The bust was taken during a 1912 excavation under Ottoman-era antiquities rules, which allowed foreign teams to divide finds. Egypt argues the transfer was misleadingly documented and has repeatedly requested its return, but Germany maintains it was acquired legally.

How did Nefertiti die?

Her fate remains unknown. She vanishes from records around Year 16 of Akhenaten’s reign. Theories range from death due to illness or plague to retirement or even execution. No tomb or mummy has been conclusively linked to her.

Conclusion: Why Nefertiti Still Matters

Nefertiti’s fame endures because she represents more than a beautiful face—she embodies transformation, agency, and mystery. As a woman who stood at the center of a religious upheaval, challenged traditional gender roles in leadership, and left behind a visual legacy that still captivates millions, her story resonates across time. Whether viewed through the lens of history, art, or cultural politics, Nefertiti forces us to reconsider what we know about power, representation, and memory in the ancient world.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?