Nonpoint source pollution (NPS) is the leading cause of water quality issues in rivers, lakes, and coastal areas across the United States and many other countries. Unlike pollution from industrial or sewage treatment plants—where contaminants enter water bodies through a single, identifiable pipe—nonpoint source pollution comes from diffuse sources. It accumulates gradually as rainwater or snowmelt moves over and through the ground, picking up pollutants along the way and depositing them into waterways. Despite decades of environmental regulation, NPS remains stubbornly difficult to manage. Its complexity arises not from a lack of awareness, but from structural, geographic, and behavioral challenges that resist conventional regulatory approaches.

The Nature of Nonpoint Source Pollution

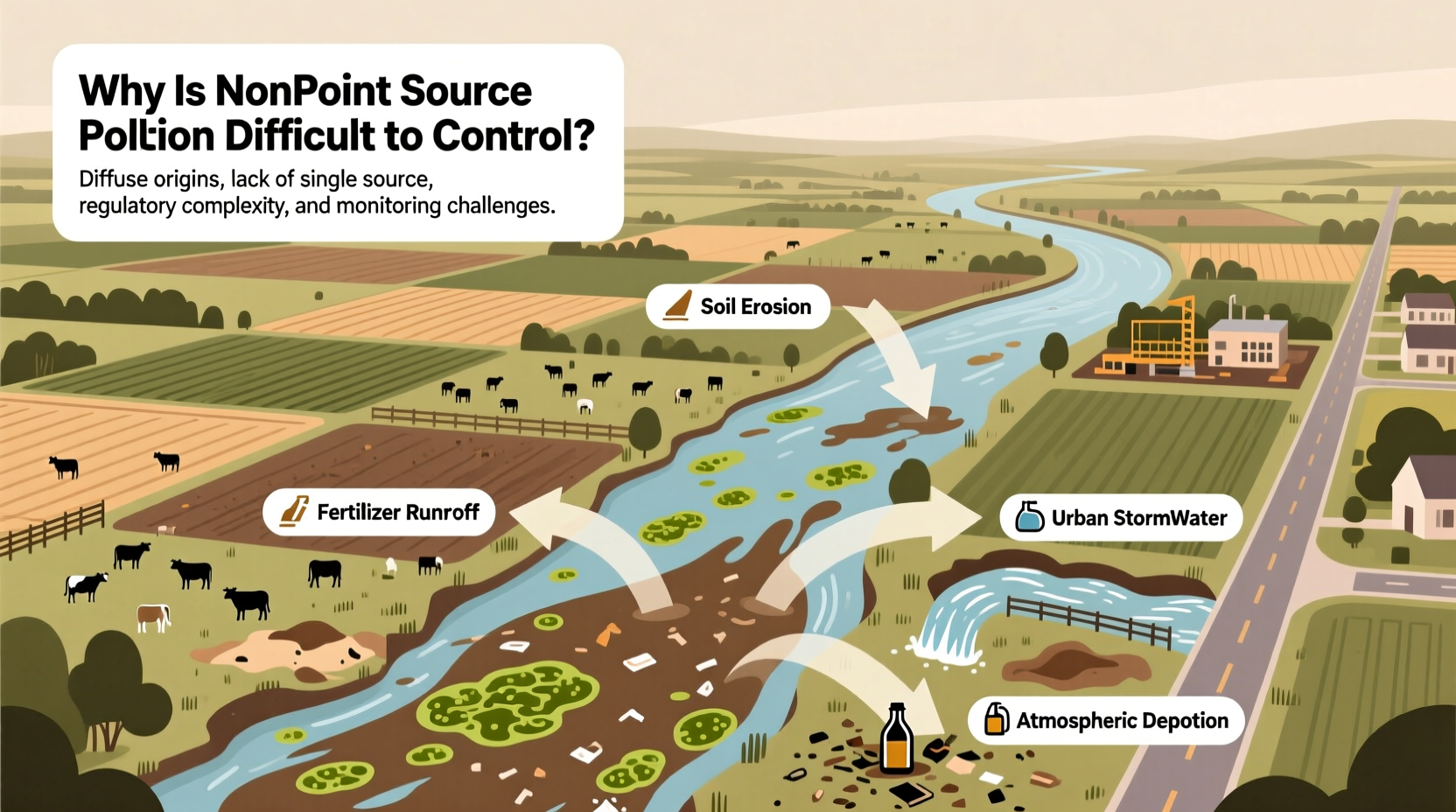

Nonpoint source pollution includes a wide range of contaminants: fertilizers and pesticides from agricultural fields, oil and heavy metals from urban roadways, sediment from construction sites, bacteria from livestock operations, and nutrients from septic systems. These pollutants do not originate from a single discharge point. Instead, they are carried by runoff from broad landscapes—farms, suburban lawns, city streets, forests undergoing logging, and even natural areas experiencing erosion.

This diffuse origin means there is no “smoking gun” facility to regulate. A factory releasing chemicals into a river can be monitored, fined, and required to install filtration systems. But how do you regulate thousands of homeowners applying excess fertilizer on their lawns? Or countless drivers whose vehicles leak motor oil onto pavement? The very definition of nonpoint source pollution makes enforcement nearly impossible under traditional command-and-control environmental policies.

Key Challenges in Controlling Nonpoint Source Pollution

Several interrelated factors make nonpoint source pollution especially hard to control:

1. Lack of Identifiable Sources

Because NPS pollution stems from widespread activities rather than centralized facilities, pinpointing responsibility is complex. No single entity can be held accountable when every landowner, driver, or farmer contributes a small amount. This diffusion of responsibility leads to a \"tragedy of the commons,\" where individuals feel little incentive to change behavior because the impact of their actions seems negligible in isolation.

2. Variability Across Landscapes

Pollution levels depend heavily on local conditions: soil type, slope, rainfall patterns, land use, and vegetation cover. What works in controlling runoff in Iowa farmland may not apply to suburban developments in Florida or mountainous regions in Colorado. This variability demands highly localized solutions, which are costly and difficult to scale.

3. Weather-Dependent Transport

NPS pollution is closely tied to precipitation. Heavy rains increase runoff volume and velocity, washing more pollutants into streams. Droughts, conversely, reduce dilution capacity in waterways, making existing contamination more concentrated. Because pollution events are episodic and weather-driven, monitoring becomes unpredictable and intermittent, complicating data collection and response planning.

4. Limited Regulatory Tools

Under the U.S. Clean Water Act, point sources require permits under the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES). No equivalent system exists for nonpoint sources. While some states have implemented voluntary programs or land-use regulations, these lack the enforcement mechanisms of federal permitting. As a result, compliance relies on education and incentives rather than mandates.

5. Economic and Social Incentives

Farmers may prioritize crop yields over nutrient management. Homeowners may value lush green lawns regardless of fertilizer use. Municipalities may delay stormwater infrastructure upgrades due to budget constraints. Without strong economic disincentives or accessible alternatives, sustainable practices remain optional rather than standard.

“Nonpoint source pollution isn’t a technical problem—it’s a governance problem. We know how to reduce runoff, but we lack the institutional frameworks to implement solutions at scale.” — Dr. Rebecca Langston, Watershed Policy Research Institute

Strategies and Best Management Practices (BMPs)

Despite the challenges, effective strategies exist to mitigate nonpoint source pollution. These rely on prevention, landscape design, and community engagement:

- Riparian buffers: Vegetated strips along waterways filter runoff and stabilize banks.

- Conservation tillage: Reduces soil disturbance in farming, minimizing erosion.

- Rain gardens and permeable pavements: Allow stormwater to infiltrate the ground instead of running off.

- Precision agriculture: Uses GPS and sensors to apply fertilizers only where needed.

- Public education campaigns: Inform residents about proper disposal of household chemicals and pet waste.

| Practice | Target Pollutant | Effectiveness | Implementation Barrier |

|---|---|---|---|

| Riparian Buffers | Sediment, Nutrients | High | Landowner cooperation |

| Urban Green Infrastructure | Oil, Metals, Runoff Volume | Moderate to High | Upfront cost |

| Fertilizer Management Plans | Nitrogen, Phosphorus | Moderate | Monitoring difficulty |

| Septic System Inspections | Bacteria, Nitrate | High | Enforcement gaps |

| Construction Site Silt Fences | Sediment | Low to Moderate | Compliance inconsistency |

Mini Case Study: Chesapeake Bay Restoration Efforts

The Chesapeake Bay, the largest estuary in the United States, has suffered for decades from excessive nitrogen and phosphorus loads—primarily from nonpoint sources like agriculture and urban runoff. In 2010, the EPA established a Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) plan requiring six states and Washington, D.C., to reduce nutrient pollution.

The strategy included both regulatory and voluntary components: funding for cover crops, upgrades to wastewater plants (a point source), and incentives for farmers to adopt nutrient management plans. By 2023, nitrogen loads had decreased by about 10% basin-wide, with notable improvements in certain tributaries.

However, progress stalled in rural areas where participation was low. One Pennsylvania county saw only 30% adoption of recommended BMPs due to limited technical assistance and distrust of government programs. This case illustrates that even well-funded, science-based initiatives struggle when they rely on voluntary action without strong local buy-in.

Actionable Checklist for Communities and Individuals

Controlling nonpoint source pollution requires coordinated effort. Use this checklist to contribute effectively:

- Dispose of household chemicals, motor oil, and medications properly—never down drains or on the ground.

- Use fertilizers and pesticides sparingly; opt for slow-release or organic alternatives.

- Install rain barrels or plant native species to reduce yard runoff.

- Participate in local watershed cleanups or monitoring programs.

- Support municipal investment in green infrastructure like bioswales and permeable sidewalks.

- Ensure your septic system is inspected every 3–5 years.

- Advocate for stronger state-level agricultural runoff regulations.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between point and nonpoint source pollution?

Point source pollution comes from a single, identifiable location, such as a factory pipe or sewage treatment plant. Nonpoint source pollution originates from multiple, diffuse sources, primarily transported by rainfall or snowmelt across landscapes.

Can nonpoint source pollution be regulated?

Direct federal regulation is limited, but states and local governments can implement land-use ordinances, stormwater management requirements, and agricultural best practices. Some programs offer financial incentives for compliance, but enforcement remains inconsistent.

How does nonpoint source pollution affect drinking water?

Nutrients like nitrates from fertilizers can contaminate groundwater, posing risks to infants and pregnant women. Pathogens from animal waste can also infiltrate wells, leading to gastrointestinal illnesses. Treating such contamination increases water utility costs and reduces supply reliability.

Conclusion: A Collective Responsibility

Nonpoint source pollution persists not because we lack solutions, but because those solutions demand widespread cooperation, long-term investment, and adaptive governance. There is no single fix—only layers of prevention, education, policy, and stewardship working in concert. Every homeowner, farmer, developer, and policymaker plays a role in either exacerbating or reducing runoff.

The difficulty in controlling nonpoint source pollution should not be an excuse for inaction. On the contrary, it underscores the need for innovation in environmental governance, greater public awareness, and sustained commitment at all levels. Small changes, when multiplied across millions of acres and households, can restore balance to degraded ecosystems.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?