Pyrite, often called “fool’s gold,” is more than just a deceptive mineral that mimics the luster of real gold. Its most striking feature—its tendency to form near-perfect cubes—has fascinated geologists, crystallographers, and collectors for centuries. But why does pyrite so frequently grow in cubic shapes? The answer lies deep within its atomic structure, environmental conditions during formation, and the elegant laws of crystallography. Understanding why pyrite is square isn’t just a curiosity—it offers profound insights into how minerals crystallize and how nature favors symmetry under specific geochemical constraints.

The Atomic Blueprint: Pyrite’s Crystal Structure

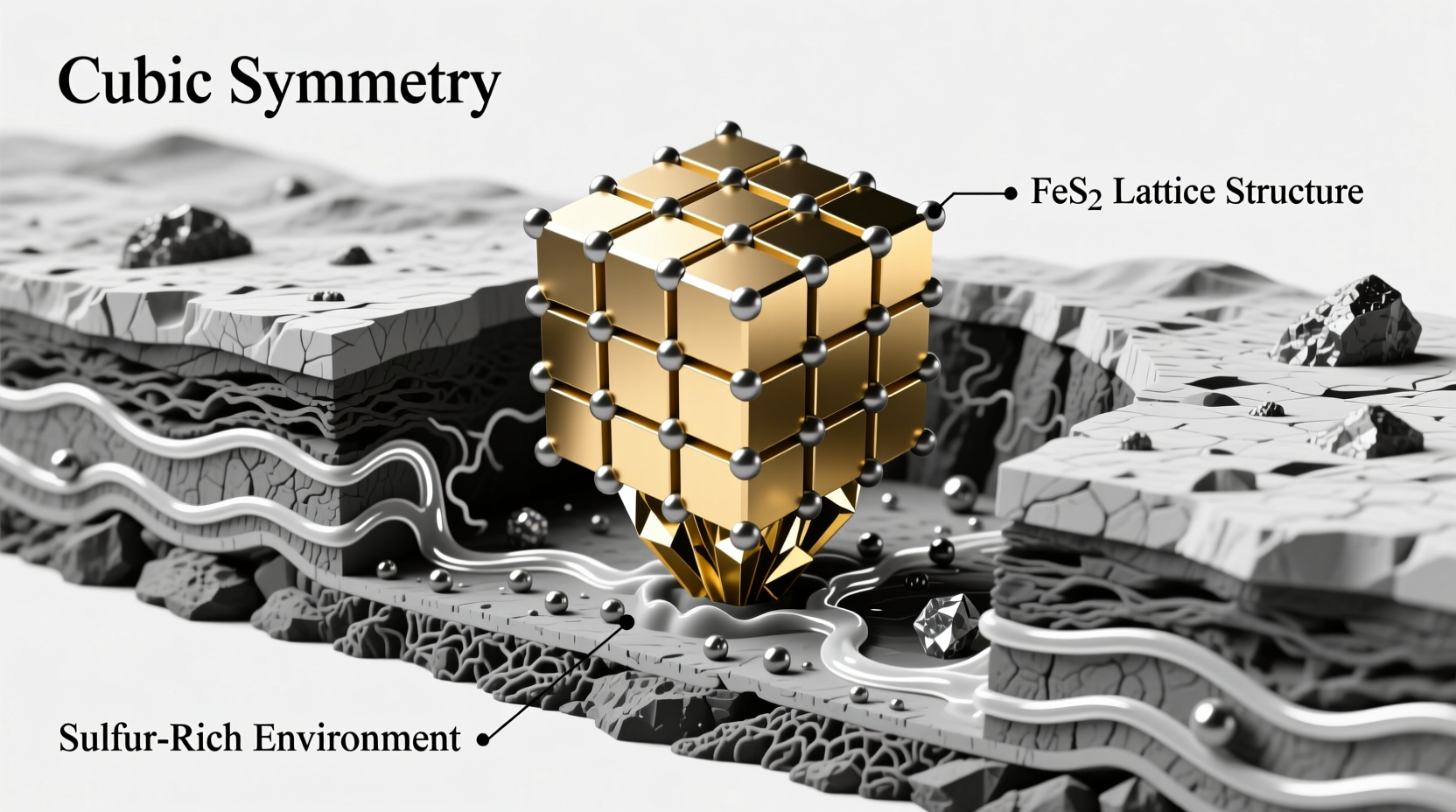

At the heart of pyrite’s cubic habit is its internal atomic arrangement. Pyrite, chemically iron disulfide (FeS₂), crystallizes in the isometric (cubic) crystal system. This means its atoms are arranged in a three-dimensional lattice with equal axes and 90-degree angles, creating natural symmetry along all directions.

In pyrite’s unit cell, each iron atom is surrounded by six sulfur atoms arranged in an octahedral configuration, while sulfur atoms occur as paired S₂ units aligned with the cube edges. This unique bonding pattern reinforces structural stability along the cubic planes, making it energetically favorable for crystals to grow equally in all three dimensions.

“Pyrite’s cubic symmetry isn't accidental—it's dictated by thermodynamics and bond geometry. When conditions allow, nature defaults to this highly stable configuration.” — Dr. Lila Chen, Mineralogist at the Geological Institute of Colorado

This atomic preference translates directly into macroscopic shape: when pyrite forms slowly in open spaces like hydrothermal veins or sedimentary nodules, it expresses its internal symmetry through well-developed cubic crystals.

Formation Environments: Where Cubic Pyrite Thrives

While pyrite can appear in various forms—massive, granular, or even spherical—the iconic cubes typically develop in environments with low kinetic interference and sufficient time for orderly growth.

- Hydrothermal veins: Hot, mineral-rich fluids percolate through rock fractures. As temperatures cool gradually, pyrite precipitates slowly, allowing ions to arrange into symmetric cubic lattices.

- Sedimentary settings: In black shales and coal beds, microbial sulfate reduction produces sulfide ions that react with iron, forming pyrite. Concretions may start as tiny cubic nuclei and grow outward if space permits.

- Metamorphic rocks: Under moderate pressure and temperature, recrystallization can enhance pyrite’s cubic expression, especially in slates and schists.

Rapid crystallization or spatial constraints often suppress cubic development, leading instead to irregular grains. But when physical and chemical conditions align—stable pH, adequate iron and sulfur supply, minimal disturbance—pyrite reveals its geometric perfection.

Crystal Growth Mechanics: Why Symmetry Wins

Cubic growth in pyrite follows fundamental principles of crystallography. Crystals grow layer by layer, with atoms attaching preferentially to high-energy sites like kinks and steps on the surface. Because pyrite’s {100} crystal faces (the cube faces) have balanced surface energy and strong atomic bonding, they tend to expand uniformly.

Moreover, pyrite exhibits a phenomenon known as face-specific growth inhibition. Trace elements like arsenic or nickel can selectively adsorb onto certain crystal faces, slowing their growth relative to others. In many cases, these impurities suppress non-cubic forms, further enhancing the dominance of cube-shaped crystals.

| Growth Factor | Effect on Cubic Formation |

|---|---|

| Slow cooling rate | Promotes large, well-formed cubes |

| Open cavity space | Allows unrestricted 3D growth |

| High Fe/S ratio | Favors stoichiometric pyrite over marcasite |

| Low fluid turbulence | Reduces distortion and twinning |

| pH near neutral | Optimizes ion availability and precipitation |

Real-World Example: The Huanzala Mine, Peru

One of the finest examples of cubic pyrite comes from the Huanzala polymetallic deposit in central Peru. Here, hydrothermal fluids rich in iron and sulfur infiltrated limestone fractures during the Cretaceous period. Over thousands of years, pyrite crystallized in vugs (small cavities), producing cubes up to several centimeters across, some perfectly intergrown or forming pyritohedrons (dodecahedra with pentagonal faces).

Mineralogists studying samples from Huanzala noted that the largest cubes formed in zones with minimal tectonic stress and consistent fluid chemistry. Smaller, distorted crystals were found near fault zones where rapid fluid pulses disrupted equilibrium. This case underscores how environmental consistency enables pyrite to express its inherent cubic symmetry.

Common Misconceptions About Pyrite Cubes

Despite their geometric precision, pyrite cubes are sometimes misunderstood:

- Misconception: All shiny yellow cubic minerals are pyrite.

Reality: Galena and chalcopyrite also form metallic-looking crystals but differ in hardness, streak color, and composition. - Misconception: Perfect cubes mean synthetic origin.

Reality: Nature routinely produces mathematically precise crystals when conditions allow. - Misconception: Pyrite always forms cubes.

Reality: Only about 30% of pyrite occurrences display distinct cubic habits; the rest are massive or framboidal (raspberry-like aggregates).

Step-by-Step: How to Identify True Cubic Pyrite

- Observe luster: Look for a brassy yellow metallic shine—brighter than gold but less malleable.

- Check hardness: Pyrite scores 6–6.5 on the Mohs scale; it scratches glass but not quartz.

- Test streak: Rub the mineral on unglazed porcelain. Pyrite leaves a greenish-black to brownish-black streak (gold leaves a yellow streak).

- Examine crystal form: True cubes will have sharp edges, flat faces, and often visible striations running parallel across each face.

- Assess density: While heavy, pyrite is less dense than gold (specific gravity ~5 vs. ~19).

FAQ: Your Questions About Cubic Pyrite Answered

Can pyrite form other shapes besides cubes?

Yes. Besides cubes, pyrite commonly forms pyritohedrons (12-faced dodecahedra), octahedra, and spherical aggregates called framboids. These reflect variations in growth kinetics and environmental conditions.

Why do some pyrite cubes have striated faces?

The striations result from alternating growth layers along the edge directions of the cube. They align with the underlying crystal lattice and are a diagnostic feature distinguishing pyrite from similar minerals like chalcopyrite.

Is cubic pyrite valuable?

While not precious like gold, high-quality cubic pyrite specimens are prized by collectors and museums for their aesthetic symmetry and scientific interest. Exceptional specimens from classic localities can sell for hundreds of dollars.

Practical Checklist for Studying Cubic Pyrite

- ☑ Use a 10x loupe to examine crystal edges and surface features

- ☑ Perform a streak test on inconspicuous areas

- ☑ Compare specific gravity using a digital scale and water displacement

- ☑ Note associated minerals (e.g., quartz, calcite, sphalerite)

- ☑ Document location and geological context for accurate interpretation

- ☑ Store specimens in dry conditions to prevent oxidation (\"pyrite decay\")

Conclusion: Embracing the Geometry of Nature

The squareness of pyrite is far more than a visual quirk—it is a direct manifestation of atomic order emerging from geological chaos. By understanding why pyrite forms cubes, we gain insight into the hidden rules governing mineral growth, the influence of environment on crystal morphology, and the deep connection between microscopic structure and macroscopic beauty.

Whether you're a geology student, a rock collector, or simply someone intrigued by nature’s precision, taking time to study cubic pyrite opens a window into Earth’s silent, mathematical elegance. The next time you hold a glittering pyrite cube, remember: you’re holding a natural sculpture shaped by physics, chemistry, and time.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?