Sourdough bread has experienced a resurgence in popularity, not just for its tangy flavor and artisanal appeal, but also for its reported digestive benefits. Many people who struggle with bloating, gas, or discomfort after eating conventional bread find they tolerate sourdough far better. But what makes this ancient form of bread so different? The answer lies in the unique fermentation process that transforms flour and water into a living culture capable of pre-digesting components that typically cause digestive distress.

Unlike commercial bread, which relies on fast-acting baker’s yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), sourdough uses a natural starter—a symbiotic culture of wild yeast and lactic acid bacteria. This extended fermentation fundamentally alters the bread’s structure, nutrient availability, and impact on the human gut. To understand why sourdough is easier to digest, we need to dive into the microbiology of fermentation and how it affects gluten, starches, phytic acid, and other compounds in wheat.

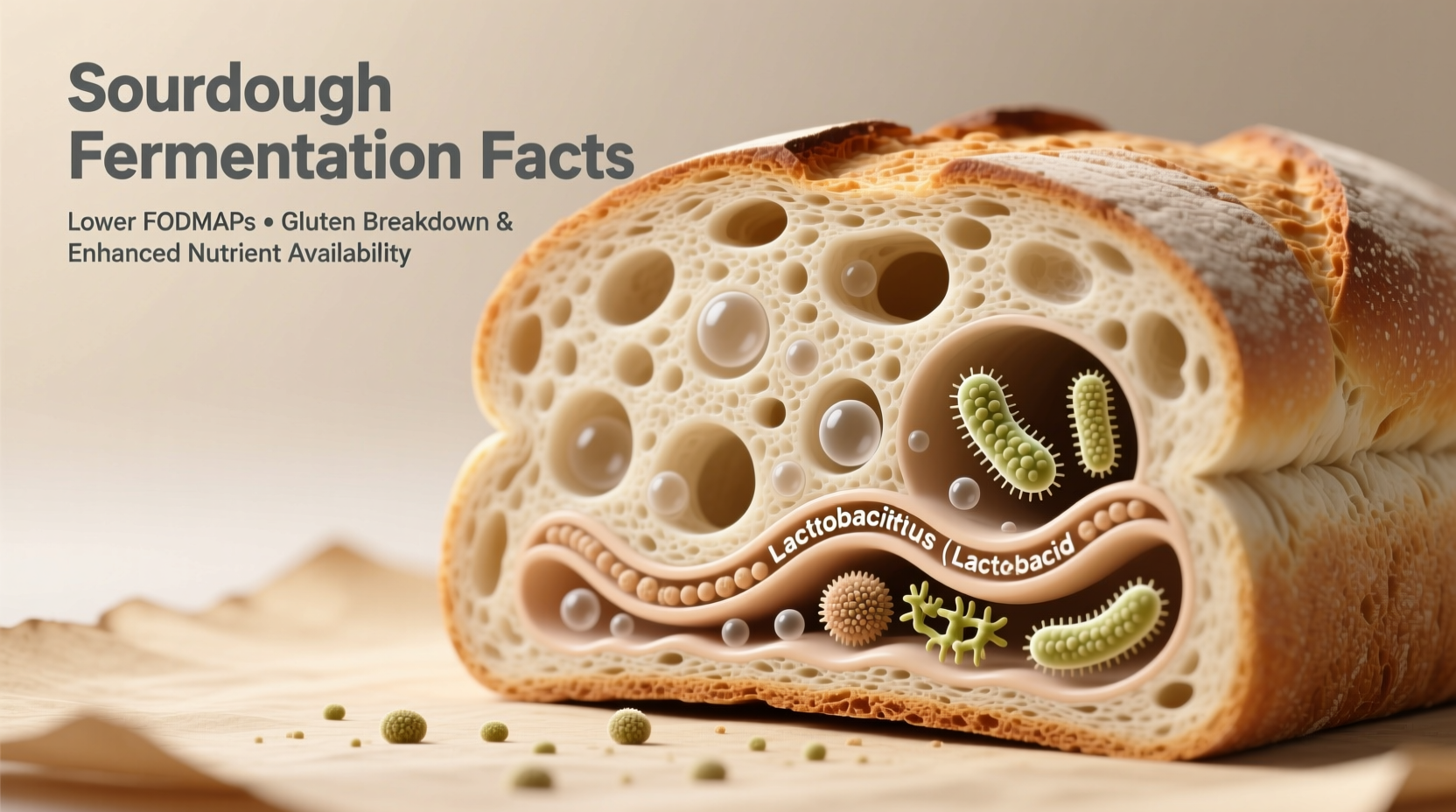

The Science Behind Sourdough Fermentation

Sourdough fermentation is a slow, biological process driven by naturally occurring microorganisms. A sourdough starter captures wild yeasts and lactic acid bacteria (LAB) from the environment—primarily Lactobacillus species such as L. sanfranciscensis. These microbes work together over hours or even days to break down carbohydrates and proteins in flour.

The lactic acid bacteria produce organic acids—mainly lactic and acetic acid—which lower the pH of the dough. This acidic environment:

- Inhibits harmful microbes

- Improves shelf life without preservatives

- Softens gluten structure

- Enhances mineral absorption

Meanwhile, wild yeasts ferment sugars and produce carbon dioxide, causing the dough to rise gradually. The combination of slow leavening and acid production sets sourdough apart from industrially produced bread, where rapid fermentation limits microbial activity.

“Sourdough fermentation is one of the oldest forms of food biotechnology. It doesn’t just make bread rise—it fundamentally improves its nutritional and digestive profile.” — Dr. Marco Gobbetti, Food Microbiologist and Fermentation Researcher

Why Is Sourdough Easier to Digest?

The primary reason sourdough is gentler on digestion comes down to three key factors: gluten modification, starch breakdown, and reduction of anti-nutrients.

Gluten Is Partially Broken Down

Gluten, a protein composite in wheat, gives bread its elasticity and chew. However, some individuals are sensitive to certain gluten peptides, particularly those resistant to human digestive enzymes. In sourdough, lactic acid bacteria secrete proteolytic enzymes that break down gluten into smaller, more digestible fragments.

A landmark study published in Clinical Nutrition found that long fermentation (over 24 hours) reduced gluten content in wheat bread to levels safe for many people with non-celiac gluten sensitivity. While sourdough is not gluten-free, the structural changes make it significantly less irritating to the gut lining.

Starches Are Pre-Digested

Complex carbohydrates in flour are broken down during fermentation into simpler sugars. Amylolytic enzymes from bacteria and wild yeast convert starch into maltose and glucose, which are then consumed by microbes. This reduces the glycemic load of the final bread, meaning it causes a slower, steadier rise in blood sugar.

This pre-digestion also means your body doesn’t have to work as hard to break down the carbohydrates, reducing the risk of fermentation in the colon—which can lead to gas and bloating.

Phytic Acid Is Neutralized

Phytic acid, found in grains and seeds, binds to minerals like iron, zinc, and calcium, making them less available for absorption. It can also irritate the gut lining in sensitive individuals. Sourdough fermentation activates phytase, an enzyme that degrades phytic acid.

Research shows that sourdough fermentation can reduce phytic acid by up to 90% compared to conventional bread-making methods. This not only improves mineral bioavailability but also reduces the potential for digestive discomfort caused by undigested grain compounds.

Fermentation Facts: What Sets Sourdough Apart

Not all sourdough is created equal. True sourdough requires time, care, and a live culture. Unfortunately, many commercially labeled “sourdough” products use shortcuts—adding vinegar or souring agents instead of real fermentation. Here’s how authentic sourdough compares to conventional bread:

| Factor | Sourdough Bread (Traditional) | Regular Commercial Bread |

|---|---|---|

| Fermentation Time | 8–24+ hours | 1–3 hours |

| Leavening Agent | Wild yeast + lactic acid bacteria | Commercial baker’s yeast |

| Gluten Structure | Partially broken down, softer network | Intact, rigid network |

| pH Level | Acidic (pH 3.8–4.5) | Nearly neutral (pH ~6.0) |

| Phytic Acid Content | Reduced by 50–90% | Mostly retained |

| Glycemic Index | Lower (~50–55) | Higher (~70–80) |

| Shelf Life (without preservatives) | 5–7 days | 2–3 days |

The data clearly shows that traditional sourdough undergoes a transformative process that enhances both nutrition and digestibility. The acidity, microbial diversity, and enzymatic activity present in properly fermented sourdough simply cannot be replicated in fast-rising industrial loaves.

Real-World Example: Sarah’s Digestive Relief

Sarah, a 38-year-old teacher from Portland, had struggled with bloating and fatigue after eating bread for years. She tested negative for celiac disease but was diagnosed with non-celiac gluten sensitivity. After eliminating most wheat products, she tried a locally baked sourdough loaf out of curiosity.

To her surprise, she felt no adverse effects—even after eating two slices with breakfast. Encouraged, she began experimenting with different sourdough bakers and eventually started making her own. Over time, she noticed not only improved digestion but also better energy levels and fewer afternoon crashes.

When she shared her experience with her dietitian, she learned that the long fermentation likely broke down problematic gluten peptides and reduced the bread’s glycemic impact. Her story isn’t unique; countless people report similar improvements when switching to traditionally fermented sourdough.

How to Choose or Make Truly Digestible Sourdough

Given the popularity of sourdough, many mass-market brands now label their products as such—even when they lack the essential fermentation characteristics. To ensure you’re getting a genuinely gut-friendly loaf, follow these guidelines:

- Check the ingredient list: Real sourdough contains only flour, water, salt, and possibly a starter. Avoid loaves with added vinegar, citric acid, or commercial yeast listed alongside “sourdough starter.”

- Look for long fermentation claims: Some artisan bakers specify fermentation times. Aim for at least 12 hours from mix to bake.

- Observe texture and taste: Authentic sourdough has a complex tang, open crumb, and chewy crust. If it tastes bland or rises too uniformly, it may be faked.

- Try baking your own: Controlling the fermentation allows you to optimize for digestibility.

Step-by-Step Guide to Maximizing Digestibility at Home

If you’re baking sourdough, consider these steps to enhance its digestive benefits:

- Use whole grain or high-extraction flours: They contain more enzymes and nutrients that support fermentation.

- Extend bulk fermentation: Allow dough to ferment at room temperature for 8–12 hours, or longer in cooler environments.

- Retard proofing in the fridge: Cold fermentation (overnight, 12–18 hours) increases acidity and further breaks down gluten and starches.

- Bake thoroughly: A well-baked loaf with a dark crust has undergone more complete starch gelatinization, aiding digestion.

- Let it rest: Allow bread to cool completely (at least 2 hours) before slicing. This lets internal starches set properly and improves texture.

FAQ: Common Questions About Sourdough and Digestion

Can people with IBS eat sourdough bread?

Many individuals with Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS), especially those sensitive to FODMAPs, find sourdough easier to tolerate. The fermentation process reduces fructans—short-chain carbohydrates in wheat that feed gut bacteria and cause gas. However, sourdough is not low-FODMAP by default. Those following a strict low-FODMAP diet should opt for sourdough made with spelt or small portions of wheat sourdough, and consult a dietitian.

Is sourdough safe for people with gluten intolerance?

Sourdough is not safe for people with celiac disease, as it still contains gluten. However, studies suggest that properly fermented sourdough may be tolerable for some with non-celiac gluten sensitivity due to partial gluten degradation. Anyone with gluten-related disorders should consult a healthcare provider before reintroducing wheat-based sourdough.

Does sourdough have probiotics?

No—baking kills the live bacteria in sourdough. While the fermentation process creates beneficial compounds (like organic acids and bioactive peptides), sourdough bread itself is not a probiotic source. However, it acts as a prebiotic by delivering fermented fibers that feed good gut bacteria.

Conclusion: Embrace the Power of Slow Fermentation

Sourdough bread isn’t just a trend—it’s a return to a deeper understanding of how food interacts with our bodies. By harnessing natural fermentation, sourdough transforms simple ingredients into a more digestible, nutritious, and flavorful staple. The science is clear: long fermentation reduces irritants, enhances nutrient availability, and supports gut health in ways that modern bread-making often overlooks.

If you’ve ever felt uncomfortable after eating bread, don’t assume the problem is wheat itself. The issue may lie in how it’s processed. Choosing or making real sourdough—made with time, care, and a living culture—can make all the difference.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?