Sourdough bread has experienced a resurgence in popularity, not just for its tangy flavor and artisanal appeal but for its potential health benefits—particularly when it comes to gut health. Unlike conventional bread made with commercial yeast, sourdough relies on a natural fermentation process using wild yeast and lactic acid bacteria. This ancient method of breadmaking transforms the structure and nutrient profile of wheat, making it more digestible and potentially beneficial for the gut microbiome. In this article, we’ll break down exactly how sourdough impacts digestive health, analyze its nutritional composition, and explain why it may be a smarter choice for those seeking better gastrointestinal wellness.

The Science Behind Sourdough Fermentation

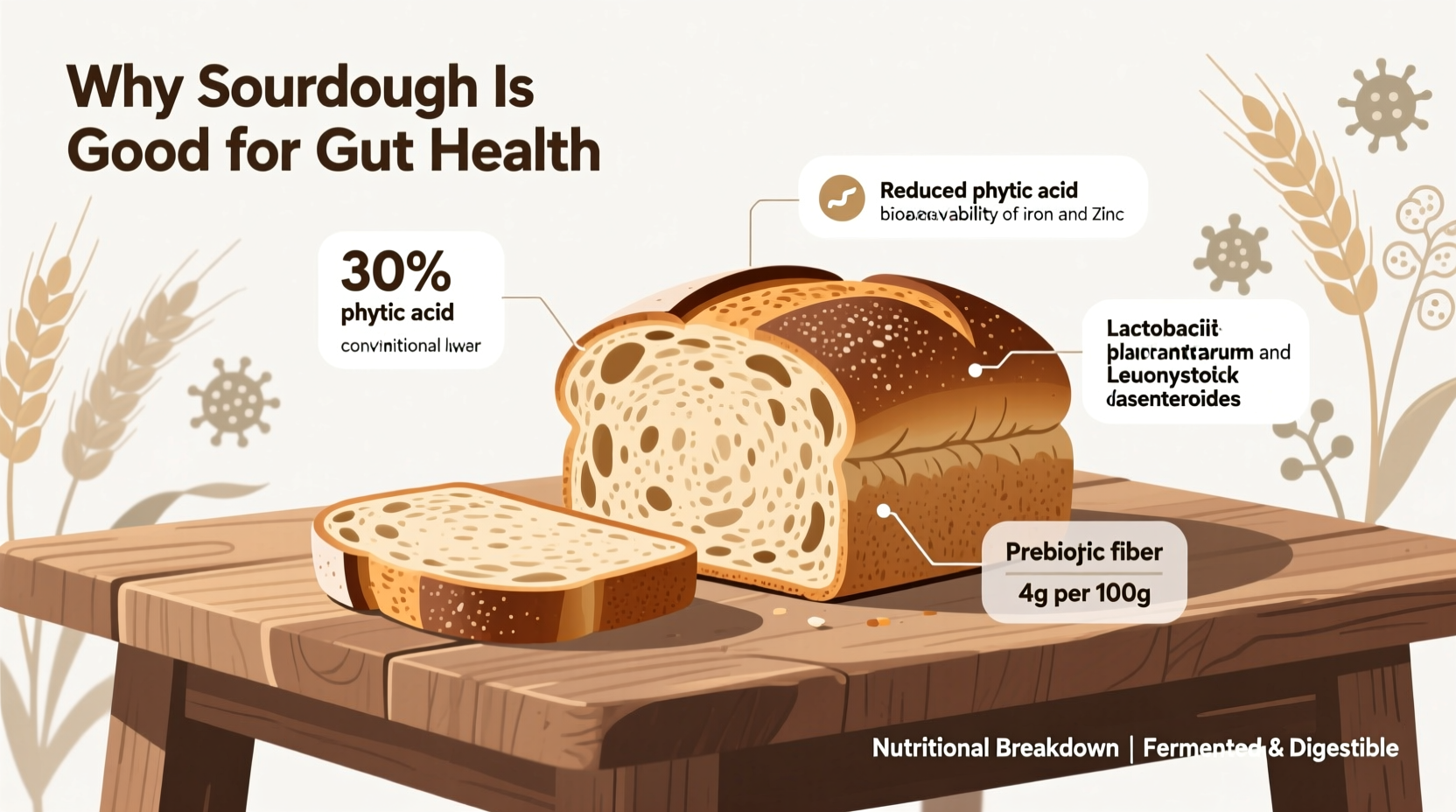

The foundation of sourdough’s gut-friendly reputation lies in its fermentation process. A sourdough starter—a mixture of flour and water—is colonized by naturally occurring microbes from the environment, primarily lactic acid bacteria (LAB) such as Lactobacillus species and wild yeasts like Saccharomyces exiguus. Over time, these microorganisms ferment the carbohydrates in flour, producing lactic and acetic acids that give sourdough its signature tang.

This extended fermentation—often lasting 8 to 24 hours—does more than enhance flavor. It initiates biochemical changes that improve the bread’s nutritional accessibility:

- Reduction of phytic acid: Phytates in grains bind to minerals like iron, zinc, and magnesium, inhibiting their absorption. Lactic acid bacteria degrade phytic acid during fermentation, increasing mineral bioavailability.

- Pre-digestion of gluten: The enzymes produced during fermentation partially break down gluten proteins, which may reduce digestive discomfort for some individuals sensitive to modern wheat.

- Lower glycemic index: Acids formed during fermentation slow starch digestion, resulting in a more gradual rise in blood sugar compared to conventional bread.

“Fermented foods like sourdough introduce beneficial microbes and metabolites that support gut barrier integrity and microbial diversity.” — Dr. Maria Rodriguez, Gut Microbiome Researcher, University of Copenhagen

Nutritional Breakdown: Sourdough vs. Conventional White Bread

To understand sourdough’s advantages, it helps to compare its nutrient profile with that of standard white bread. While both are made from similar base ingredients, fermentation alters key nutritional metrics.

| Nutrient (per 100g) | Sourdough Bread | Conventional White Bread | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calories | 260 kcal | 265 kcal | Comparable energy density |

| Carbohydrates | 50 g | 51 g | Slightly lower due to fermentation loss |

| Fiber | 3.5 g | 2.7 g | Higher fiber retention due to processing |

| Protein | 9 g | 8.5 g | Improved amino acid availability |

| Fat | 3.2 g | 3.3 g | Negligible difference |

| Iron | 2.4 mg (13% DV) | 1.8 mg (10% DV) | Better absorption due to reduced phytates |

| Magnesium | 45 mg (11% DV) | 25 mg (6% DV) | Significantly higher bioavailability |

| Glycemic Index (GI) | ~53 (Medium) | ~75 (High) | Sourdough causes slower glucose release |

The data shows that while macronutrients are broadly similar, sourdough offers improved micronutrient delivery and metabolic effects. Its lower glycemic impact makes it a better option for blood sugar management, which indirectly supports gut health by reducing inflammation.

How Sourdough Supports the Gut Microbiome

The human gut hosts trillions of microorganisms collectively known as the microbiota. A balanced microbiome aids digestion, regulates immunity, and even influences mood. Diet plays a crucial role in shaping this ecosystem, and fermented foods like sourdough can contribute positively.

Although sourdough is baked—killing live cultures—it still delivers functional compounds produced during fermentation:

- Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs): Lactic and acetic acids survive baking and reach the colon, where they nourish beneficial bacteria and help maintain an acidic environment hostile to pathogens.

- Exopolysaccharides: Some LAB produce prebiotic-like fibers that feed good bacteria such as Bifidobacteria.

- Reduced FODMAPs: Fermentation breaks down certain short-chain carbohydrates (like fructans) that can cause bloating in people with IBS. Studies suggest well-fermented sourdough may be better tolerated.

A 2021 study published in Nutrients found that participants who consumed traditionally fermented sourdough reported fewer instances of abdominal discomfort and improved stool consistency compared to those eating regular whole wheat bread.

Real-World Example: Managing Digestive Sensitivity with Sourdough

Consider the case of James, a 42-year-old office worker with mild non-celiac gluten sensitivity. He experienced regular bloating and fatigue after eating sandwiches made with store-bought whole grain bread. After switching to a locally baked, long-fermented sourdough loaf made from organic whole wheat, he noticed a marked improvement within two weeks.

James didn’t eliminate gluten entirely—he wasn’t diagnosed with celiac disease—but his symptoms diminished significantly. His dietitian attributed this change to sourdough’s reduced levels of fermentable oligosaccharides and partially degraded gluten peptides. While not a cure, sourdough offered a practical dietary compromise that improved his quality of life without requiring strict elimination.

This scenario reflects a growing trend: individuals discovering that traditional food preparation methods can make modern diets more compatible with digestive health—even when dealing with grain-based foods often labeled as “problematic.”

Step-by-Step: How to Choose the Most Gut-Friendly Sourdough

Not all sourdough is created equal. Many supermarket loaves labeled “sourdough” contain only a trace of starter and rely on added vinegar or yeast to mimic tanginess. To reap genuine gut health benefits, follow this selection guide:

- Check the ingredient list: True sourdough contains only flour, water, salt, and a sourdough starter. Avoid products listing baker’s yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), vinegar, or preservatives.

- Look for fermentation time: Ask your baker or check packaging for fermentation duration. Breads fermented for 12+ hours offer greater phytate reduction and pre-digestion.

- Opt for whole grains: Whole wheat, rye, spelt, or einkorn flours provide more fiber and polyphenols, enhancing prebiotic effects.

- Assess texture and aroma: Authentic sourdough has a complex sourness, irregular crumb structure, and crisp crust. Mass-produced versions tend to be uniform and mildly tangy at best.

- Support local artisans: Small-scale bakers are more likely to use traditional methods than industrial producers focused on speed and shelf life.

Common Misconceptions About Sourdough and Gut Health

Despite its benefits, sourdough is sometimes misunderstood:

- Myth: Sourdough is gluten-free.

Factual: It is not gluten-free. While fermentation reduces gluten content, it remains unsafe for individuals with celiac disease. - Myth: All sourdough is equally healthy.

Factual: Processing matters. Fast-risen, enriched, or highly processed sourdough lacks the full benefits of slow fermentation. - Myth: Sourdough acts like a probiotic.

Factual: The baking process kills live bacteria, so it doesn’t deliver probiotics. However, it provides postbiotics—metabolites like organic acids—that support gut health.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can sourdough help with bloating and gas?

Yes, for many people. The fermentation process breaks down hard-to-digest carbohydrates like fructans and reduces phytates, which can contribute to gas and bloating. Those with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) may find traditionally made sourdough easier to tolerate than other breads—though individual responses vary.

Is sourdough suitable for people with diabetes?

Sourdough generally has a lower glycemic index than other breads, leading to a slower, more stable rise in blood glucose. This makes it a better carbohydrate choice for blood sugar management. However, portion control is still important, and individuals should monitor their personal response.

Does homemade sourdough offer more benefits than store-bought?

Potentially, yes. Homemade sourdough allows full control over ingredients, fermentation time, and flour type. Long, cold fermentation in a home setting maximizes nutrient availability and digestibility. Store-bought options vary widely—artisanal brands may match homemade quality, but mass-market versions often fall short.

Action Checklist: Maximizing Gut Benefits from Sourdough

To get the most out of sourdough for digestive wellness, follow this actionable checklist:

- ✅ Read labels carefully—only flour, water, salt, and starter should be listed.

- ✅ Prioritize sourdough made with whole or ancient grains.

- ✅ Choose loaves fermented for at least 12 hours.

- ✅ Pair sourdough with fiber-rich toppings like avocado, hummus, or sauerkraut to boost prebiotic intake.

- ✅ Monitor your body’s response—keep a food journal if you have digestive concerns.

- ✅ Avoid overconsumption—even healthy bread should be eaten in moderation.

Conclusion: Embracing Tradition for Modern Gut Wellness

Sourdough bread stands at the intersection of tradition and science, offering a compelling example of how time-honored food practices can align with contemporary health goals. Its fermentation-driven transformation enhances nutrient absorption, reduces antinutrients, and supports a balanced gut microbiome—all while delivering satisfying flavor and texture. While not a miracle food, authentic sourdough represents a more thoughtful approach to grain consumption in an era of digestive disorders and ultra-processed diets.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?