Sourdough bread has surged in popularity over the past decade, not just for its tangy flavor and artisanal appeal, but because it’s often described as a “healthier” alternative to conventional bread. But what does science say? Is sourdough truly better for you — or is it just another food trend wrapped in wellness marketing?

The answer lies in its unique fermentation process. Unlike most commercial breads that rely on packaged yeast for rapid leavening, sourdough uses a natural starter — a living culture of wild yeast and lactic acid bacteria. This slow fermentation doesn’t just affect taste and texture; it fundamentally changes the bread’s nutritional profile, digestibility, and metabolic impact.

This article breaks down the science behind why sourdough stands apart from regular bread, exploring how microbial activity transforms starches, reduces anti-nutrients, and supports gut health — all while offering a more stable energy release.

The Science of Fermentation: What Sets Sourdough Apart

The core difference between sourdough and regular bread lies in fermentation. Most store-bought bread uses commercial baker’s yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) to make dough rise quickly — often within a few hours. In contrast, sourdough relies on a symbiotic culture of wild yeast and lactic acid bacteria (primarily Lactobacillus species) that ferment the dough over 8 to 24 hours.

This extended fermentation triggers biochemical changes:

- Pre-digestion of carbohydrates: Bacteria break down complex starches into simpler sugars, which are easier for humans to digest.

- Acid production: Lactic and acetic acids lower the pH of the dough, altering protein structure and slowing starch breakdown during digestion.

- Phytate reduction: Naturally occurring phytic acid in grains binds minerals like iron, zinc, and calcium, reducing their absorption. The acidic environment in sourdough activates phytase, an enzyme that degrades phytates.

These transformations don’t just improve shelf life and flavor — they directly influence how your body processes the bread.

Digestibility and Gluten Sensitivity

Many people who struggle with bloating or discomfort after eating regular bread report feeling better when consuming genuine sourdough. While sourdough is not gluten-free, research suggests it may be more tolerable for some individuals with mild gluten sensitivity.

A landmark study published in Clinical Nutrition found that participants with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) experienced fewer gastrointestinal symptoms when eating low-FODMAP sourdough bread compared to standard wheat bread. The fermentation process appears to reduce certain fermentable carbohydrates that contribute to gas and bloating.

Moreover, the lactic acid bacteria in sourdough partially break down gluten proteins. One Italian study showed that prolonged fermentation with selected Lactobacillus strains reduced gluten content by up to 97% in experimental settings — though this does not make it safe for celiac disease patients.

“Sourdough fermentation modifies gluten structure and reduces immunoreactive peptides, which may explain improved digestive tolerance.” — Dr. Marco Gobbetti, Professor of Food Microbiology, University of Naples

For those without celiac disease but sensitive to modern processed wheat, sourdough offers a gentler alternative due to these structural changes.

Glycemic Response and Blood Sugar Control

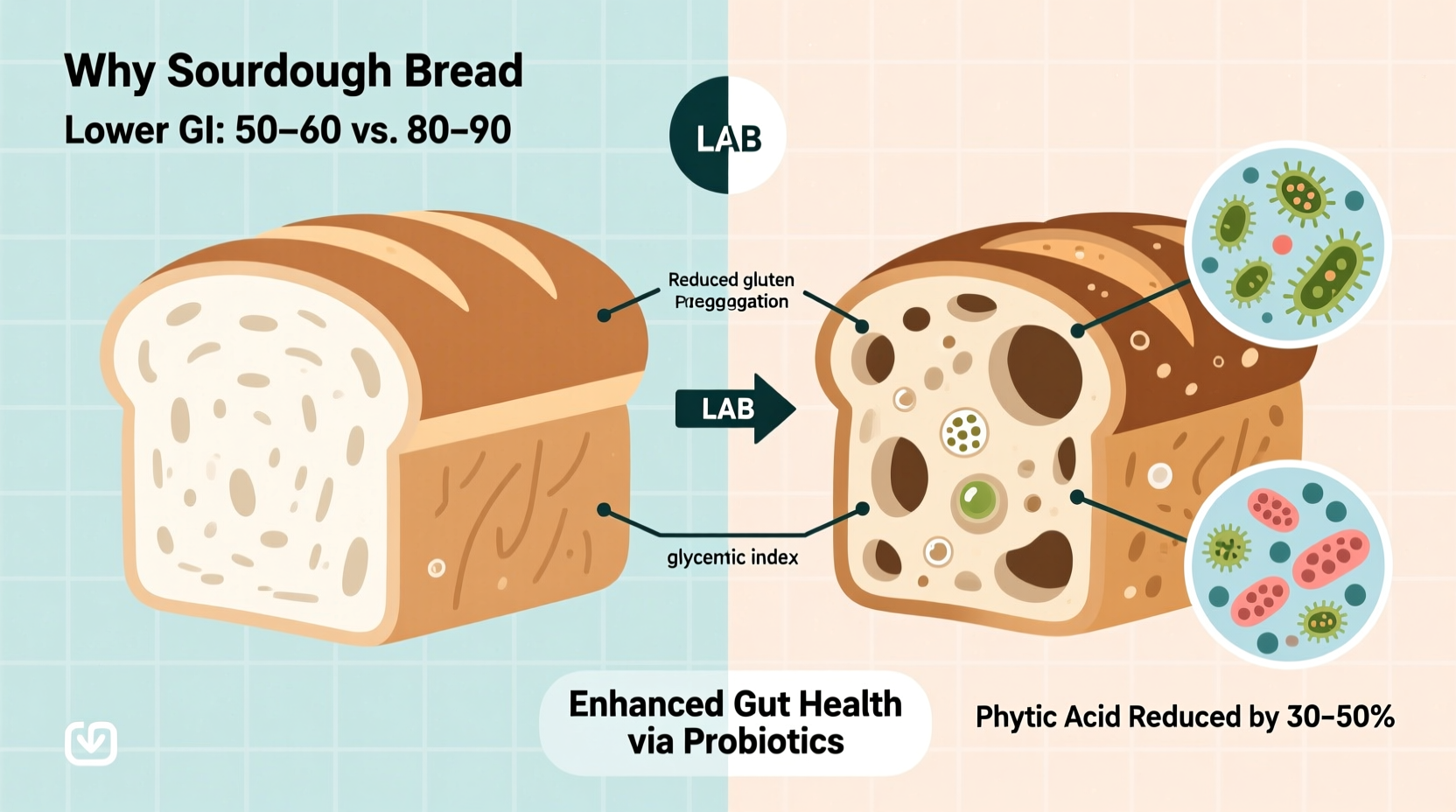

One of the most compelling advantages of sourdough is its effect on blood sugar. Multiple studies confirm that sourdough bread elicits a lower glycemic response than conventionally leavened bread — even when made from the same flour.

In a 2008 study published in the European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, participants who ate sourdough rye bread had significantly lower post-meal glucose and insulin spikes compared to those eating yeast-leavened bread. The acid in sourdough alters starch gelatinization, slowing down the rate at which enzymes break it down into glucose.

This slower digestion translates into sustained energy and reduced insulin demand — a major benefit for metabolic health, weight management, and diabetes prevention.

| Bread Type | Average Glycemic Index (GI) | Insulin Response |

|---|---|---|

| White Sandwich Bread | 75 (High) | High |

| Whole Wheat Bread | 69–74 (Medium-High) | Moderate-High |

| Sourdough Bread (Wheat) | 53–58 (Low-Medium) | Moderate |

| Sourdough Rye Bread | 40–48 (Low) | Low |

The organic acids in sourdough also enhance satiety. People tend to feel fuller longer after eating sourdough, which can help regulate appetite and reduce overall calorie intake.

Gut Health and Microbiome Benefits

The human gut thrives on diversity — both in diet and microbial exposure. Sourdough’s lactic acid bacteria, while largely inactivated during baking, leave behind metabolites that may support gut health.

During fermentation, Lactobacillus produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), antimicrobial peptides, and bioactive compounds. Though the live bacteria don’t survive the oven, their metabolic byproducts remain and may act as prebiotics — food for beneficial gut microbes.

Additionally, the breakdown of fructans (a type of FODMAP) during long fermentation makes sourdough more compatible with low-FODMAP diets, often recommended for IBS sufferers.

While sourdough isn’t a probiotic food (since the microbes are killed by heat), its indirect contribution to gut balance through improved nutrient availability and reduced irritants is increasingly recognized in nutritional science.

Mini Case Study: Sarah’s Experience with Digestive Comfort

Sarah, a 38-year-old teacher from Portland, had struggled with chronic bloating and fatigue after meals containing bread. She avoided gluten entirely for months, but missed the comfort of toast and sandwiches. On her dietitian’s suggestion, she tried authentic sourdough bread — fermented for at least 18 hours — sourced from a local bakery using organic whole wheat.

After incorporating one slice daily, she noticed no bloating, stable energy levels, and improved bowel regularity. Blood work six weeks later showed slightly improved iron and zinc levels — nutrients previously borderline low, likely due to poor absorption from phytate-rich processed foods.

Her experience aligns with emerging evidence: real sourdough isn’t just easier to digest — it may enhance mineral uptake and metabolic function.

Nutrient Availability: Unlocking Hidden Minerals

Whole grains contain essential minerals like iron, magnesium, zinc, and calcium. However, these are often bound by phytic acid, making them less bioavailable. This compound acts as a plant’s natural pest deterrent but can interfere with human mineral absorption when consumed in excess.

Sourdough fermentation creates ideal conditions for phytase — the enzyme that breaks down phytic acid — to become highly active. The acidic environment (pH 3.8–4.5) combined with time allows up to 90% degradation of phytates, depending on flour type and fermentation duration.

In contrast, quick-rise commercial breads show minimal phytate reduction. A 2007 study in Food Chemistry demonstrated that traditional sourdough fermentation increased mineral absorption by 50–70% compared to yeast-leavened counterparts.

How to Identify Real Sourdough (Not Just Marketing)

Not all bread labeled “sourdough” delivers the health benefits described above. Many supermarket brands use small amounts of starter for flavor but rely primarily on commercial yeast and short fermentation — negating most advantages.

To ensure you’re getting genuinely fermented sourdough, follow this checklist:

- Check the ingredients: True sourdough contains only flour, water, salt, and possibly a starter. Avoid loaves with added yeast (especially “yeast,” “instant yeast,” or “baker’s yeast”).

- Look for a tangy taste: Authentic sourdough has a distinct sourness from lactic acid. Mild or bland flavor suggests insufficient fermentation.

- Ask about fermentation time: Reputable bakeries will know how long their dough ferments. Aim for 12 hours or more.

- Observe texture: Long-fermented sourdough has irregular air pockets, a chewy crumb, and a crisp crust.

- Buy from artisan sources: Local bakeries or farmers' markets are more likely to produce real sourdough than mass producers.

Do’s and Don’ts When Choosing Sourdough

| Do | Don't |

|---|---|

| Choose bread with only flour, water, salt, starter | Buy bread with added commercial yeast |

| Select whole grain or rye-based sourdough | Assume “sourdough-style” means real fermentation |

| Store in paper bag for first 1–2 days to preserve crust | Keep in plastic immediately (traps moisture, softens crust) |

| Freeze extras for longevity | Refrigerate bread (accelerates staling) |

Frequently Asked Questions

Is sourdough bread gluten-free?

No, unless specifically made with gluten-free flours. Traditional sourdough uses wheat, rye, or barley — all containing gluten. However, fermentation reduces gluten content and alters its structure, potentially improving tolerance for non-celiac individuals with sensitivity.

Can I make sourdough at home safely?

Yes, and it's encouraged. Homemade sourdough gives you full control over ingredients and fermentation time. Just maintain your starter regularly with fresh flour and water, and keep it at room temperature when active. Discard moldy or foul-smelling starters immediately.

Does sourdough have fewer carbs than regular bread?

Not significantly in total carbohydrate content. However, due to altered starch structure and lower glycemic impact, sourdough results in a slower, smaller rise in blood sugar — meaning your body treats the carbs differently, even if the count is similar.

Conclusion: A Return to Traditional Wisdom Backed by Science

Sourdough bread isn’t inherently magical — but its traditional preparation taps into biological processes that modern industrial baking often skips. Through slow fermentation, sourdough becomes more than just risen dough; it transforms into a food that supports digestion, stabilizes blood sugar, enhances nutrient absorption, and respects the complexity of human metabolism.

Choosing real sourdough over conventional bread is a small dietary shift with meaningful ripple effects. It reconnects us with ancestral food practices while aligning with contemporary scientific understanding of gut health and metabolic wellness.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?