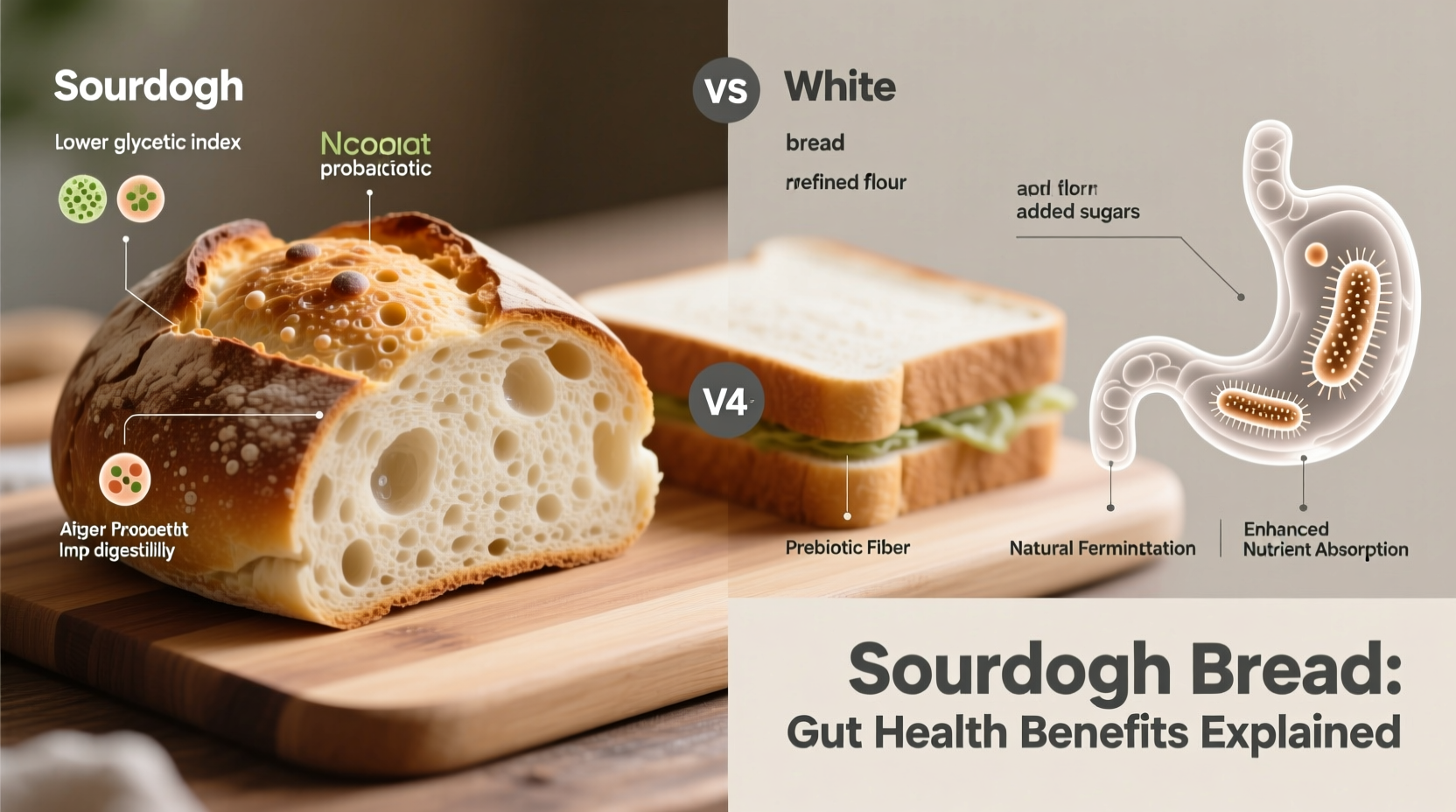

For centuries, sourdough has been a staple in traditional diets across Europe and beyond. Unlike modern white bread, which relies on commercial yeast for rapid leavening, sourdough undergoes a slow fermentation process using wild yeast and lactic acid bacteria. This natural method not only enhances flavor but also transforms the nutritional profile of the bread—especially in ways that benefit digestive health. As gut health gains recognition as a cornerstone of overall well-being, understanding why sourdough is healthier than white bread becomes increasingly important.

The difference lies not just in ingredients but in how those ingredients are processed. White bread is typically made from refined flour stripped of bran and germ, then rapidly fermented and baked. Sourdough, by contrast, uses longer fermentation times that break down complex carbohydrates and proteins, making nutrients more accessible and reducing compounds that can irritate the gut. Let’s explore the science behind these benefits and what they mean for your microbiome, digestion, and long-term health.

The Gut Microbiome: Why It Matters

The human gut hosts trillions of microorganisms—bacteria, viruses, fungi—that collectively form the gut microbiome. This internal ecosystem plays a critical role in digestion, immune function, inflammation regulation, and even mood. A balanced microbiome thrives on dietary fiber and prebiotics, while poor food choices can lead to dysbiosis—an imbalance linked to bloating, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and chronic diseases.

Refined grains like those in white bread offer little to no fiber or beneficial compounds. They’re quickly broken down into glucose, spiking blood sugar and feeding less desirable microbes. In contrast, sourdough bread, particularly when made with whole grain or high-extraction flours, supports microbial diversity through its unique fermentation byproducts.

“Fermented foods like sourdough introduce bioactive compounds that interact directly with our gut lining and microbiota, promoting resilience and metabolic balance.” — Dr. Maria Rodriguez, Gut Health Researcher at the Institute for Nutritional Science

Fermentation: The Key Difference

The fundamental distinction between sourdough and white bread lies in fermentation. While white bread uses baker’s yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) for fast rising—often under two hours—sourdough relies on a starter culture containing wild yeast and Lactobacillus species. This natural fermentation can last 8 to 24 hours or more, allowing biochemical changes that improve digestibility and nutrient availability.

During this time, lactic acid bacteria produce organic acids such as lactic and acetic acid. These lower the pH of the dough, which:

- Inhibits mold and pathogens

- Slows starch digestion, leading to a gentler rise in blood sugar

- Breaks down phytic acid, an antinutrient that binds minerals like iron and zinc

- Preactivates enzymes that aid human digestion

This extended acidic environment mimics conditions found in the human stomach and small intestine, effectively “predigesting” components of the grain before consumption.

Digestive Benefits of Sourdough Over White Bread

Many people report fewer digestive issues when switching from white bread to sourdough—even if both contain gluten. This isn’t coincidental. Several factors contribute to improved gastrointestinal comfort:

Reduced Gluten Content and Altered Structure

Gluten gives bread its elasticity, but it can be difficult to digest for some individuals. During sourdough fermentation, proteolytic enzymes from lactic acid bacteria partially break down gluten proteins into smaller peptides. Studies show reductions of up to 40–50% in immunoreactive gluten fragments, though sourdough is still not safe for those with celiac disease.

For people with non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS), this partial degradation may reduce bloating, gas, and abdominal discomfort commonly triggered by conventional bread.

Lower Glycemic Index

Sourdough bread generally has a glycemic index (GI) 20–30% lower than white bread. The organic acids produced during fermentation slow the rate at which starches are converted into glucose in the bloodstream. This results in steadier energy levels and reduced insulin demand—important for metabolic health and gut stability.

Spikes in blood sugar promote inflammation and alter gut motility, potentially encouraging overgrowth of opportunistic microbes. By moderating glucose release, sourdough helps maintain a calmer internal environment.

Enhanced Mineral Absorption

Phytic acid, naturally present in grains, binds essential minerals like iron, calcium, magnesium, and zinc, preventing their absorption. The prolonged fermentation in sourdough activates phytase—an enzyme that degrades phytic acid—freeing up these nutrients.

In one study published in the journal *Food Chemistry*, sourdough fermentation reduced phytate content in whole wheat bread by over 60%, significantly improving mineral bioavailability compared to yeast-leavened counterparts.

Nutrient Comparison: Sourdough vs. White Bread

| Nutrient | Sourdough Bread (Whole Grain) | White Bread (Commercial) | Benefit Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fiber | 3–5g per slice | 0.5–1g per slice | Supports regularity and feeds beneficial gut bacteria |

| Glycemic Index | ~50–54 | ~70–75 | Slower glucose release reduces gut stress and insulin spikes |

| Phytic Acid | Low (degraded during fermentation) | High | Lower levels increase absorption of iron, zinc, and calcium |

| Prebiotic Compounds | Present (arabinose, xylooligosaccharides) | Minimal | Feed Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli in the colon |

| Gluten Integrity | Partially degraded | Intact | Easier to digest for sensitive individuals |

Real-Life Impact: A Mini Case Study

Consider Sarah, a 38-year-old office worker who struggled with daily bloating and sluggish digestion. She ate toast every morning, usually opting for soft white sandwich bread because it was convenient. After reading about fermented foods, she switched to a locally baked sourdough loaf made with 100% whole wheat and a 16-hour fermentation cycle.

Within two weeks, Sarah noticed reduced post-meal fullness and more consistent bowel movements. Her afternoon energy crashes diminished, and she felt less reliant on caffeine. While other dietary changes were minimal, she attributed much of the improvement to eliminating ultra-refined grains and introducing a fermented staple.

Her experience aligns with clinical observations: patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders often respond positively to replacing processed breads with traditionally fermented alternatives—even without eliminating gluten entirely.

How to Choose Truly Healthy Sourdough

Not all sourdough is created equal. Supermarket versions often mislead consumers with labels like “sourdough-style” despite using added vinegar and commercial yeast instead of real fermentation. To ensure you're getting authentic, gut-friendly sourdough, follow this checklist:

- Ingredients list should include only: Flour, water, salt, and possibly a sourdough starter. Avoid vinegar, yeast, dough conditioners, or preservatives.

- Texture: Chewy crumb with irregular air pockets—not uniform or overly soft.

- Taste: Mildly tangy, not bland or sweet.

- Bakery source: Artisan bakers who ferment for 8+ hours are more likely to produce biologically active sourdough.

- Label claims: Look for “naturally leavened,” “fermented for X hours,” or “made with live culture.”

Step-by-Step: Transitioning from White Bread to Sourdough

Making the switch doesn’t have to be abrupt. Follow this timeline to ease your digestive system into the change:

- Week 1: Replace one slice of white bread per day with sourdough. Monitor any changes in digestion or energy.

- Week 2: Increase to one full serving (two slices) every other day. Try different flours—rye, spelt, or einkorn—for varied prebiotic profiles.

- Week 3: Use sourdough exclusively for sandwiches and toast. Pair with healthy fats (avocado, olive oil) and protein to further stabilize blood sugar.

- Ongoing: Experiment with homemade sourdough to control ingredients and fermentation length. Even basic home baking yields superior results to mass-produced loaves.

This gradual approach allows your gut microbiota time to adapt to increased fiber and new bacterial metabolites like short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which are produced when gut bugs ferment fiber from whole grains.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is sourdough bread gluten-free?

No, unless specifically made with gluten-free flour. However, the fermentation process breaks down some gluten proteins, making sourdough easier to tolerate for people with mild sensitivities—but not for those with celiac disease.

Can sourdough help with bloating?

Yes, many people report less bloating due to improved digestibility, lower FODMAP content (especially after proper fermentation), and reduced phytates. Rye-based sourdoughs may be particularly effective, though individual responses vary.

Does sourdough have probiotics?

While sourdough contains live lactic acid bacteria during fermentation, most are killed during baking. However, the beneficial effects come from the postbiotics—metabolic byproducts like organic acids and degraded antinutrients—that remain in the final product and support gut health.

Conclusion: Make the Smart Swap for Long-Term Gut Health

Choosing sourdough over white bread isn’t just a trend—it’s a return to ancestral wisdom grounded in modern science. The slow fermentation process fundamentally improves the bread’s impact on your gut, offering better nutrient absorption, stabilized blood sugar, and enhanced microbial balance. Unlike highly processed white bread, which contributes to inflammation and gut dysbiosis, real sourdough acts as a functional food that supports digestive wellness.

The shift requires attention to quality: seek out genuinely fermented loaves from transparent sources. Whether store-bought or homemade, incorporating true sourdough into your diet is a simple yet powerful step toward nurturing your gut—and by extension, your entire body.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?