For millions of people around the world, a meal isn’t complete without a fiery kick. Whether it’s a plate of Sichuan hot pot, a bowl of vindaloo, or a few dashes of habanero sauce, spicy food holds an almost magnetic appeal. But what starts as curiosity often turns into habit—and for many, a full-blown craving. Why do so many people willingly subject themselves to burning tongues and runny noses? The answer lies not in masochism, but in biology. Spicy food isn’t just flavorful—it’s chemically intoxicating, thanks to a compound called capsaicin and its powerful interaction with our nervous system and brain chemistry.

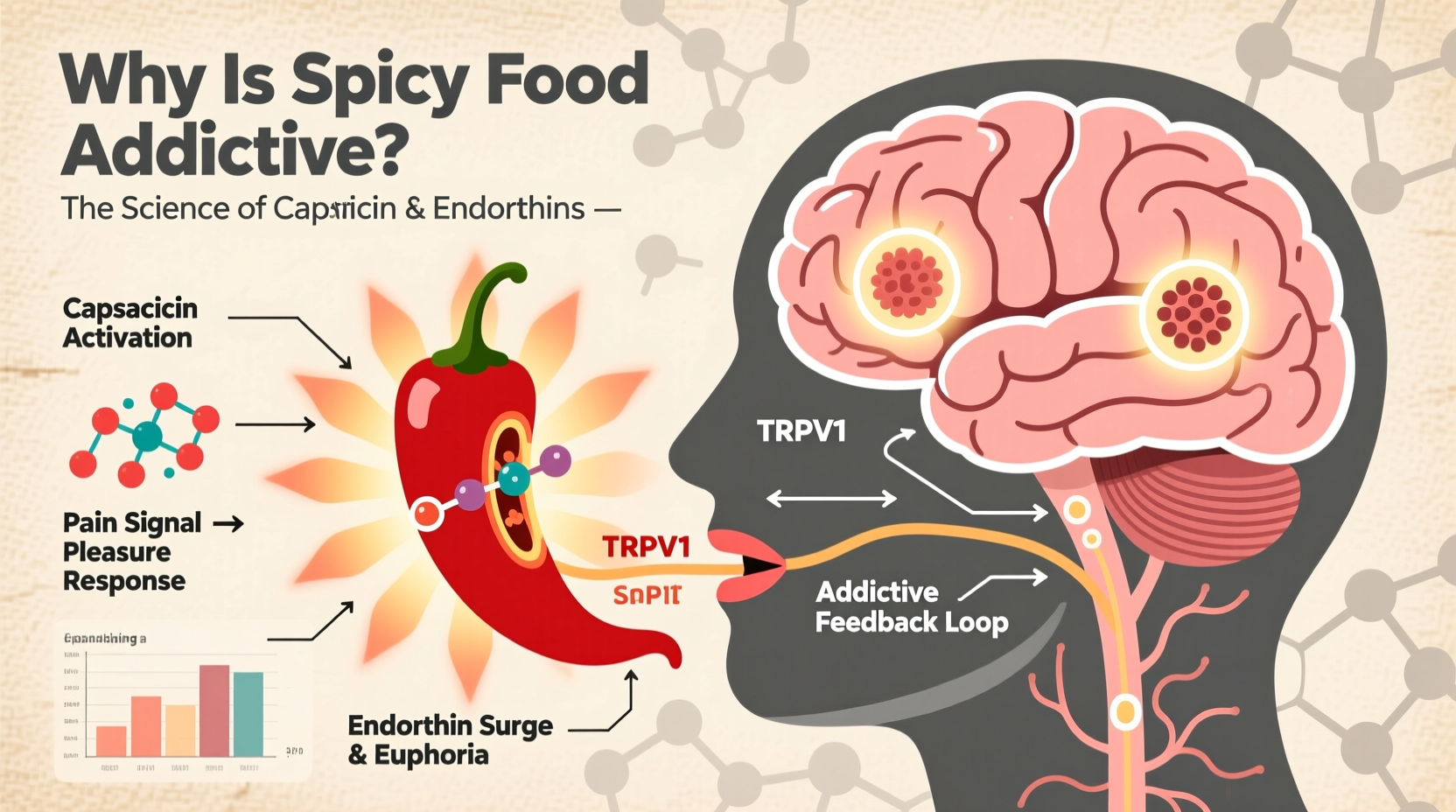

The sensation of spiciness isn't a taste—it's a form of irritation. Capsaicin, the active component in chili peppers, tricks the body into thinking it’s under thermal attack. In response, the brain releases endorphins, natural opioids that dull pain and generate euphoria. This neurochemical chain reaction creates a cycle of discomfort followed by pleasure—similar to the highs experienced during exercise or thrill-seeking. Over time, this feedback loop conditions the brain to crave the burn, making spicy food not just enjoyable, but genuinely addictive.

The Biology of Burn: How Capsaicin Triggers Pain (and Pleasure)

Capsaicin doesn’t activate taste buds like salt or sugar. Instead, it binds to a specific receptor in the mouth and throat known as TRPV1 (transient receptor potential vanilloid 1). These receptors evolved to detect actual heat—temperatures above 43°C (109°F)—as a protective mechanism against burns. When capsaicin binds to TRPV1, it sends a false signal to the brain: “Danger! Too hot!”

The result? A cascade of physiological responses: increased salivation, sweating, flushed skin, and a racing heart. You’re not actually being burned, but your body reacts as if you are. This perceived threat activates the sympathetic nervous system—the same system responsible for the fight-or-flight response.

But here’s where things get interesting: the brain doesn’t just respond to pain; it tries to counteract it. To manage the distress caused by capsaicin, the hypothalamus signals the pituitary gland to release endorphins—specifically beta-endorphins—into the bloodstream. These neurotransmitters bind to opioid receptors in the brain, reducing pain perception and producing a mild sense of well-being, even euphoria. It’s the same system activated by intense physical activity, laughter, or certain types of stress.

“Spicy food creates a controlled stress response. The body thinks it’s in danger, but instead of harm, it gets a reward in the form of endorphins. That’s the core of the addiction.” — Dr. Paul Rozin, Professor of Psychology, University of Pennsylvania, pioneer in the study of culinary behavior

This neurochemical payoff is why many describe eating spicy food as a “rush” or “high.” And like other rewarding stimuli, repeated exposure strengthens the neural pathways associated with pleasure, reinforcing the desire to repeat the experience.

The Endorphin Effect: Why We Chase the Burn

Endorphins are the body’s natural painkillers, but they also play a crucial role in mood regulation. They interact with the same receptors as morphine and codeine, though far more gently. When released in significant amounts, they can produce feelings of calm, satisfaction, and even mild euphoria. This is central to understanding why spicy food becomes habitual.

Consider the experience of someone new to spicy cuisine. Their first bite of a jalapeño might be overwhelming—tears, coughing, a desperate search for milk. But if they push through, the body responds by releasing endorphins to mitigate the discomfort. After the storm passes, they may feel oddly relaxed or energized. Repeat this cycle several times, and the brain begins to associate the initial pain with the subsequent reward.

This process mirrors the mechanism behind other forms of benign masochism—the enjoyment of controlled negative experiences. Skydiving, roller coasters, horror movies—all involve temporary fear or stress followed by relief and excitement. Spicy food fits this model perfectly: pain is brief, consequences are minimal, and the neurological payoff is real.

Building Tolerance: How Regular Consumption Changes Your Body

One reason spicy food becomes more appealing over time is desensitization. Repeated exposure to capsaicin causes TRPV1 receptors to become less responsive. Nerve endings in the mouth literally \"burn out\" temporarily, reducing sensitivity. This is why seasoned spice-eaters can handle ghost peppers while others struggle with black pepper.

Desensitization works both peripherally (in the mouth) and centrally (in the brain). As the body grows accustomed to capsaicin, it requires more heat to trigger the same level of endorphin release. This leads to escalation—a phenomenon known as the “spice treadmill.” Enthusiasts often report needing progressively hotter foods to achieve the same high.

Interestingly, this adaptation isn’t permanent. Stop eating spicy food for several weeks, and sensitivity returns. This reversibility suggests that the addiction isn’t chemical in the traditional sense (like nicotine or caffeine), but rather behavioral and neurological—driven by learned reward patterns.

Moreover, regular consumption of capsaicin has been linked to long-term health benefits, including improved metabolism, reduced inflammation, and lower appetite. These subtle advantages may further reinforce the habit, creating a positive feedback loop beyond mere pleasure.

Psychological and Cultural Factors Behind the Craving

Biology alone doesn’t explain the global love affair with spice. Culture plays a massive role. In countries like Thailand, India, Mexico, and Nigeria, spicy food is deeply embedded in tradition, identity, and daily life. From childhood, people are conditioned to enjoy heat, often viewing bland food as unappetizing or incomplete.

There’s also a social dimension. Sharing a fiery meal can be a bonding experience, a test of courage, or a display of resilience. Eating extremely spicy food in groups often involves laughter, groaning, and mutual encouragement—amplifying the emotional high. Social validation reinforces the behavior, making it more likely to persist.

Psychologically, some individuals are “sensation seekers”—a personality type characterized by a desire for novel, intense experiences. Research shows that high sensation seekers are more likely to enjoy spicy food, bungee jumping, and extreme sports. For them, the burn isn’t a deterrent; it’s the point.

“We’ve found a strong correlation between spicy food preference and traits like openness to experience and thrill-seeking. It’s not just about taste—it’s about identity.” — Dr. Nadia Byrnes, Nutrition Scientist, Purdue University

Step-by-Step Guide to Developing a Spicy Food Tolerance

If you’re intrigued by the rush of spicy food but aren’t ready to tackle a Carolina Reaper, building tolerance is a manageable process. Follow this timeline to safely train your body and mind to enjoy increasing levels of heat.

- Week 1–2: Start Mild – Incorporate small amounts of mild chilies like poblano or Anaheim into meals. Try one slice of jalapeño on tacos or a dash of cayenne in scrambled eggs.

- Week 3–4: Introduce Medium Heat – Move to serrano peppers, medium-hot salsas, or dishes with fresh red chilies. Pay attention to your body’s signals—mild discomfort is normal; severe pain is not.

- Week 5–6: Increase Frequency – Eat spicy food 3–4 times per week. Consistency helps desensitize TRPV1 receptors faster.

- Week 7–8: Experiment with Hot Sauces – Try sauces rated between 5,000–50,000 Scoville units (like Tabasco or Sriracha). Use sparingly at first.

- Week 9+: Gradual Escalation – Test hotter varieties like habanero or Scotch bonnet. Always have dairy (milk, yogurt) on hand to neutralize capsaicin if needed.

Remember: hydration and dairy are your allies. Water spreads capsaicin; milk (especially whole) contains casein, which breaks it down.

Do’s and Don’ts of Eating Spicy Food

| Do’s | Don’ts |

|---|---|

| Eat slowly to allow your body to adjust | Chug water when your mouth burns (it won’t help) |

| Pair spicy food with dairy (yogurt, cheese, milk) | Eat extremely spicy food on an empty stomach |

| Build tolerance gradually over weeks | Compete with others in hot-eating challenges |

| Listen to your body—stop if you feel nauseous or dizzy | Ignore signs of gastrointestinal distress |

| Use capsaicin-rich foods to enhance flavor, not just for heat | Assume everyone enjoys spice—always ask before serving |

Mini Case Study: From Spice Novice to Hot Sauce Connoisseur

Mark, a 32-year-old office worker from Ohio, never liked spicy food. The smell of chili powder made him cough. But after moving to New Mexico for a job, he was invited to weekly taco nights with coworkers who doused their food in homemade green chile sauce. Reluctantly, he tried a small bite.

It was brutal. His face turned red, his nose ran, and he drank three glasses of milk. But 20 minutes later, he felt unusually alert and cheerful. Curious, he tried again the next week—this time with half a teaspoon of sauce. Over time, he began adding more. Within six months, he was making his own hot sauces using ghost peppers and fermented chilies.

“It’s not just about the flavor,” Mark says. “After a stressful day, eating something really hot gives me a reset. It’s like a mental cleanse. I look forward to it.”

His story illustrates how environment, repetition, and neurochemical rewards can transform aversion into addiction.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can you become physically dependent on spicy food?

No, capsaicin does not cause physical dependence like drugs or alcohol. However, you can develop a psychological craving due to the endorphin release and habit formation. Withdrawal symptoms don’t occur, but some people miss the “high” if they stop eating spicy food.

Does everyone experience the endorphin rush from spicy food?

Not equally. Genetic differences affect TRPV1 sensitivity, and personality traits like sensation-seeking influence enjoyment. Some people simply don’t find the burn rewarding and may never develop a taste for spice.

Is eating very spicy food dangerous?

For most healthy adults, no. While extreme cases (like competitive eating) can lead to gastric distress or even rare complications like thunderclap headaches, everyday consumption of spicy food is safe and may offer health benefits. Those with acid reflux, ulcers, or irritable bowel syndrome should consult a doctor before increasing spice intake.

Conclusion: Embracing the Burn Mindfully

The allure of spicy food goes far beyond flavor. It’s a dance between pain and pleasure, mediated by capsaicin and amplified by the brain’s own opioid system. What begins as a sensory challenge evolves into a ritual of reward—one that millions return to again and again. Understanding the science behind this phenomenon doesn’t diminish the experience; it enriches it.

Whether you’re a lifelong chilihead or a curious beginner, the key is balance. Respect your body’s limits, appreciate the cultural depth of spicy cuisine, and recognize the biological wisdom behind the burn. Spicy food isn’t just addictive because it’s hot—it’s addictive because it makes us feel alive.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?