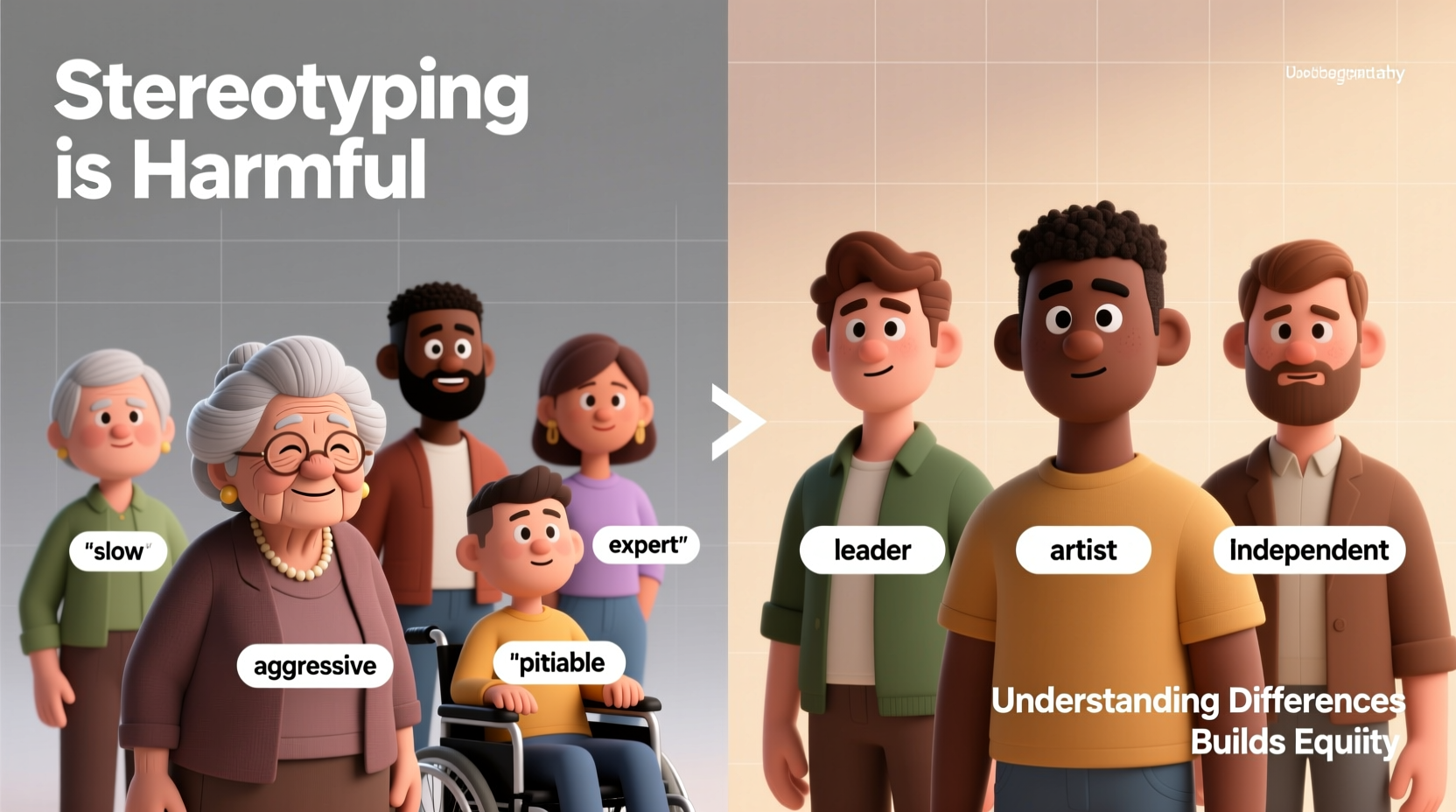

Stereotyping is a common mental shortcut—humans naturally categorize information to make sense of the world. However, when these generalizations are applied to people based on their race, gender, religion, age, or other characteristics, they become dangerous. Stereotypes reduce individuals to oversimplified labels, ignoring personal experiences, talents, and complexities. While often subtle or even unintentional, stereotyping has far-reaching consequences that damage relationships, reinforce inequality, and undermine social cohesion.

The Psychology Behind Stereotyping

Stereotypes originate from cognitive processes designed to conserve mental energy. The human brain uses schemas—mental frameworks—to organize information efficiently. When we encounter someone unfamiliar, our minds may automatically apply existing stereotypes to fill in gaps. This process, known as implicit bias, operates below conscious awareness and influences behavior without deliberate intent.

While this mechanism once served evolutionary purposes, in modern diverse societies, it leads to misjudgments and unfair assumptions. For example, assuming someone is unqualified for a job because of their accent or background can result in missed opportunities and workplace discrimination. Research shows that repeated exposure to stereotypes strengthens neural pathways that reinforce biased thinking, making it harder to see people as individuals.

“Stereotypes are not just false beliefs—they are tools of power that justify exclusion and maintain systemic inequalities.” — Dr. Lisa Chen, Social Psychologist, Stanford University

Harmful Effects of Stereotyping on Individuals

The personal toll of being stereotyped can be profound. Constantly being judged through a reductive lens leads to emotional distress, lowered self-esteem, and internalized oppression. When people are repeatedly told—or made to feel—that they are lazy, aggressive, unintelligent, or overly emotional based on group identity, some begin to believe these narratives.

This phenomenon, known as stereotype threat, occurs when individuals fear confirming negative stereotypes about their group. Studies show that stereotype threat can impair performance in academic, professional, and social settings. For instance, female students may underperform in math tests if reminded of the stereotype that women are less capable in STEM fields—even if they don’t personally believe it.

Social and Systemic Consequences

Beyond individual harm, stereotyping fuels broader patterns of injustice. It shapes policies, hiring practices, educational access, and law enforcement outcomes. Consider the over-policing of minority communities due to stereotypes linking certain racial groups with criminality. These biases contribute to disproportionate incarceration rates and erode trust in public institutions.

In workplaces, managers may unconsciously favor candidates who “fit” the organizational culture—a code often rooted in ethnic or class-based norms. Women and minorities are frequently passed over for leadership roles due to assumptions about assertiveness, commitment, or competence. Such practices perpetuate homogeneity and limit innovation.

Educational systems also reflect stereotyping. Teachers may have lower expectations for students from marginalized backgrounds, which affects grading, recommendations, and classroom engagement. These micro-inequities accumulate over time, creating long-term disparities in achievement and opportunity.

Common Stereotypes and Their Real-World Impact

| Stereotype | Target Group | Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| “All Asians are good at math” | Asian Americans | Pressure to conform; dismissal of non-STEM interests |

| “Black men are dangerous” | Black males | Racial profiling; higher police violence risk |

| “Women aren’t leaders” | Professional women | Underrepresentation in executive roles |

| “Older workers can’t adapt” | Employees over 50 | Age discrimination in hiring and promotions |

| “Muslims are terrorists” | Islamic communities | Xenophobia; hate crimes; social isolation |

A Real-World Example: The Case of Maria Thompson

Maria Thompson, a Black woman with an MBA from a top university, applied for a senior marketing role at a national retail chain. During her interview, the panel questioned whether she would “fit in with the brand’s upscale image.” Though equally or better qualified than other candidates, she was not selected. Later, an insider revealed that one interviewer commented, “She seemed too intense—we want someone more polished.”

Maria’s experience reflects how stereotypes about demeanor and professionalism disproportionately affect Black professionals. Her qualifications were overshadowed by unconscious bias tied to tone, appearance, and cultural expression. Despite filing a complaint, no formal action was taken. This case illustrates how stereotyping operates subtly but decisively in decision-making, blocking equity even in organizations with diversity initiatives.

How to Recognize and Reduce Stereotyping

Eliminating stereotyping requires both personal reflection and structural change. Awareness is the first step. Everyone holds implicit biases—acknowledging them is not a sign of prejudice but of growth potential. The following checklist offers practical actions to counteract stereotyping in daily life:

✅ Anti-Stereotyping Checklist

- Pause before making assumptions about someone’s abilities, intentions, or background.

- Seek out diverse perspectives in media, books, and conversations.

- Challenge jokes or comments that rely on group-based humor.

- Engage in perspective-taking: ask yourself how you’d feel if judged by a stereotype.

- Support inclusive policies at work and in community organizations.

- Take an Implicit Association Test (IAT) to uncover hidden biases.

- Call out stereotyping when safe to do so—silence enables continuation.

Step-by-Step Guide to Interrupting Bias

- Notice: Identify when a stereotype surfaces in your thoughts or conversation.

- Question: Ask yourself, “Is this belief based on evidence or assumption?”

- Correct: Replace the stereotype with specific, individualized knowledge.

- Act: Make decisions based on facts, not generalizations.

- Reflect: Regularly assess your interactions for patterns of bias.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can positive stereotypes be harmful too?

Yes. Even seemingly complimentary stereotypes—like “Asians are naturally smart” or “Black athletes are gifted”—are harmful. They create pressure to conform, invalidate individual effort, and lead to resentment when someone doesn’t meet the expectation. They also obscure real challenges faced by members of those groups.

Is stereotyping the same as discrimination?

Not exactly. Stereotyping is the cognitive act of holding generalized beliefs about a group. Discrimination is the behavioral outcome—the unfair treatment based on those beliefs. Stereotyping often precedes and enables discrimination, though one can exist without the other in isolated cases.

Can education eliminate stereotyping?

Education helps but isn’t enough on its own. While learning about different cultures increases awareness, deep-seated biases require active unlearning. Sustained exposure to diverse individuals as equals, combined with accountability and policy changes, is necessary for meaningful progress.

Conclusion: Building a World Beyond Labels

Stereotyping may be a natural cognitive habit, but it is not an excuse for injustice. Its consequences ripple across lives, institutions, and generations. By recognizing how stereotypes operate—often invisibly—we gain the power to disrupt them. Every interaction is an opportunity to see the person, not the label.

Change begins with self-awareness and extends into collective action. Whether in schools, boardrooms, or neighborhoods, challenging stereotypes means advocating for fairness, listening deeply, and valuing individuality over assumptions. The goal isn’t perfection but persistent effort toward a more equitable world.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?