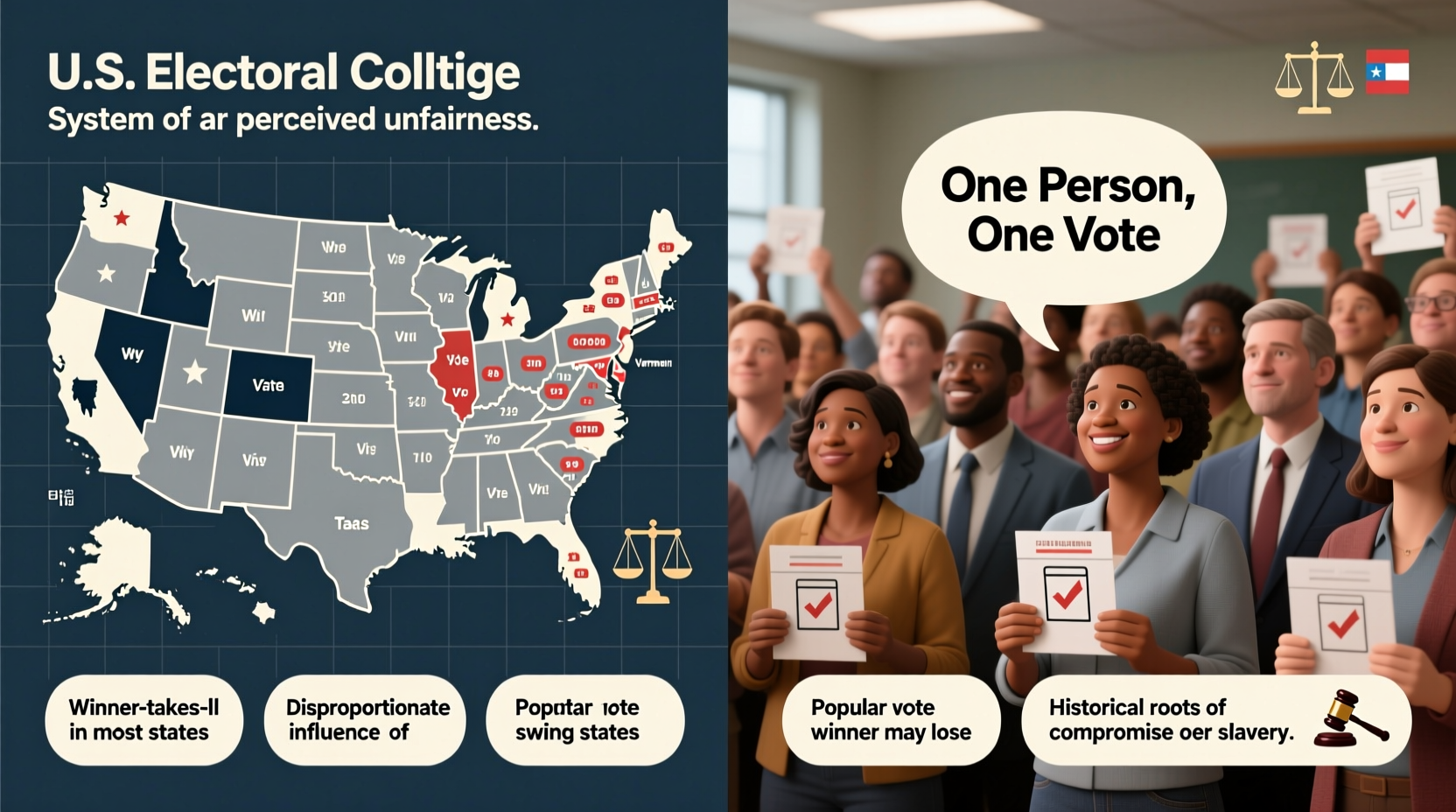

The United States elects its president through a unique mechanism known as the Electoral College—a system established by the Constitution in 1787. While it was designed to balance power between populous and less populous states, many critics argue that it no longer serves democratic fairness in the modern era. Over the past several decades, growing scrutiny has surrounded the Electoral College due to outcomes where the winner of the popular vote did not become president. This article examines the core arguments explaining why many believe the system is fundamentally unfair, supported by data, expert insights, and historical examples.

Disproportionate Influence of Small States

One of the most frequently cited reasons the Electoral College is considered unfair is the disproportionate influence granted to smaller states. Each state receives electoral votes equal to its total number of U.S. Senators (always two) plus its number of Representatives in the House (based on population). This means even the least populous states—like Wyoming, Vermont, and Alaska—receive at least three electoral votes despite having populations under 600,000.

In contrast, larger states like California or Texas have significantly more people per electoral vote. For example:

| State | Population (approx.) | Electoral Votes | People per Electoral Vote |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wyoming | 584,000 | 3 | ~195,000 |

| California | 39,500,000 | 54 | ~731,000 |

| Texas | 30,000,000 | 40 | ~750,000 |

| Vermont | 643,000 | 3 | ~214,000 |

This imbalance gives voters in less populous states significantly more weight per capita. A voter in Wyoming effectively has over three times the electoral influence of a voter in California. Critics argue this violates the principle of “one person, one vote,” a cornerstone of representative democracy.

“The current Electoral College system creates a situation where some votes count more than others simply based on geography. That’s antithetical to equal representation.” — Dr. Jane Harper, Political Science Professor at Georgetown University

Winner-Takes-All Amplifies Regional Bias

Most states use a winner-takes-all approach to allocate their electoral votes. Regardless of whether a candidate wins a state by 50.1% or 70%, they receive all of its electoral votes. This system marginalizes minority voters within states and incentivizes candidates to focus only on competitive \"swing states.\"

As a result, presidential campaigns often ignore large portions of the country. For instance, in the 2020 election, over 90% of campaign events were held in just 11 swing states. Voters in safe Democratic or Republican states—such as Oklahoma or Massachusetts—rarely see visits from candidates or receive targeted outreach.

This dynamic distorts national priorities. Candidates tailor policies to appeal to voters in battleground states like Florida, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, sometimes at the expense of broader national interests.

Popular Vote vs. Electoral Outcome Mismatches

Five times in U.S. history, the candidate who won the national popular vote lost the presidency due to the Electoral College. The most recent occurrences were in 2000 and 2016:

- 2000: Al Gore won the popular vote by over 540,000 votes but lost the Electoral College after the Supreme Court halted the Florida recount.

- 2016: Hillary Clinton received nearly 3 million more votes nationwide than Donald Trump but lost key swing states by narrow margins, costing her the electoral majority.

These discrepancies undermine public confidence in the legitimacy of the outcome. When a candidate wins the presidency without winning the most votes, it raises concerns about democratic accountability. In a direct election system, such reversals would be impossible.

A Mini Case Study: The 2016 Election

In 2016, Donald Trump secured victory by winning Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania—each by less than 1%. These three states totaled 46 electoral votes, enough to tip the election despite losing the popular vote by a wide margin. Meanwhile, Clinton won California by nearly 4 million votes, but due to the winner-takes-all rule, those additional votes had no impact beyond securing the state’s 55 electoral votes.

This scenario illustrates how geographic clustering of votes can lead to skewed outcomes. Millions of votes in non-competitive states effectively do not influence the final result, leading to voter disenfranchisement in both safe and landslide states.

Barriers to Third-Party and Independent Candidates

The Electoral College reinforces a two-party system by making it nearly impossible for third-party candidates to gain traction. Because electoral votes are awarded on a winner-takes-all basis in most states, a candidate needs overwhelming regional concentration to win even a single state.

For example, in 1992, Ross Perot won 19% of the popular vote—the highest for a third-party candidate in decades—but received zero electoral votes because he didn’t win any state. This lack of proportional representation discourages alternative voices and limits voter choice.

Under a national popular vote system, even a strong showing of 15–20% could translate into meaningful political influence and media attention, potentially reshaping the political landscape.

Efforts to Reform or Replace the System

While abolishing the Electoral College requires a constitutional amendment—difficult to achieve due to small-state dominance in the Senate—alternative reform efforts exist. One notable initiative is the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC).

Under this agreement, participating states pledge to award their electoral votes to the winner of the national popular vote, regardless of their own state’s outcome. The compact takes effect only when enough states join to reach 270 electoral votes—the threshold needed to win the presidency.

As of 2024, 17 jurisdictions (including California, New York, and Illinois) have joined, totaling 209 electoral votes. Once 61 more are secured, the system would effectively bypass the Electoral College without amending the Constitution.

Step-by-Step: How the National Popular Vote Compact Works

- States pass legislation to join the NPVIC.

- Each member state agrees to assign its electors to the national popular vote winner.

- The compact remains inactive until member states collectively hold 270+ electoral votes.

- Once activated, the president will always be the candidate who received the most votes nationwide.

- The Electoral College remains in place structurally, but its function changes de facto.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why wasn't the popular vote system adopted originally?

The Founding Fathers distrusted direct democracy and feared populous states would dominate elections. They created the Electoral College as a compromise between congressional selection and popular vote, reflecting the federal structure of the new nation.

Does the Electoral College prevent urban dominance in elections?

Some supporters argue yes—that it forces candidates to appeal beyond major cities. However, critics counter that swing-state dynamics already concentrate attention on suburban areas in a few key states, not broad rural or urban engagement nationwide.

Would eliminating the Electoral College benefit one political party?

Analysis is mixed. While Democrats have recently benefited from popular vote totals, shifts in demographics and regional alignment mean either party could gain advantage depending on the election cycle. The primary argument for reform is fairness, not partisan gain.

Checklist: Understanding Electoral College Criticisms

- ☑ Evaluate whether your vote feels equally weighted compared to voters in other states

- ☑ Consider how often your state is ignored during presidential campaigns

- ☑ Reflect on past elections where the popular vote winner lost

- ☑ Research whether your state has joined the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact

- ☑ Discuss with others how a direct election might change campaign strategies and policy focus

Conclusion

The debate over the Electoral College is ultimately about what kind of democracy Americans want. Is it one where every vote carries equal weight, regardless of zip code? Or one where structural advantages preserve state-based power balances at the cost of vote equality? Historical precedent does not justify continued acceptance of an outdated system when it repeatedly produces undemocratic outcomes.

Reforming or replacing the Electoral College is not about overturning tradition—it’s about aligning the election process with modern democratic values. Whether through constitutional amendment or interstate compacts, change is possible. Citizens, policymakers, and advocates must continue pushing for a system where the will of the majority is not just respected, but decisive.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?