The human small intestine may be called \"small,\" but in terms of length, it’s anything but. Measuring approximately 20 to 23 feet (6 to 7 meters) in a living adult, it far exceeds the large intestine in length—despite its misleading name. This organ plays a central role in digestion and nutrient absorption, and its remarkable size is no accident. The extended length is a biological adaptation essential for sustaining human life through efficient energy extraction from food. Understanding why the small intestine is so long—and how its structure enables its critical functions—reveals the sophistication of human physiology.

Anatomy and Structure of the Small Intestine

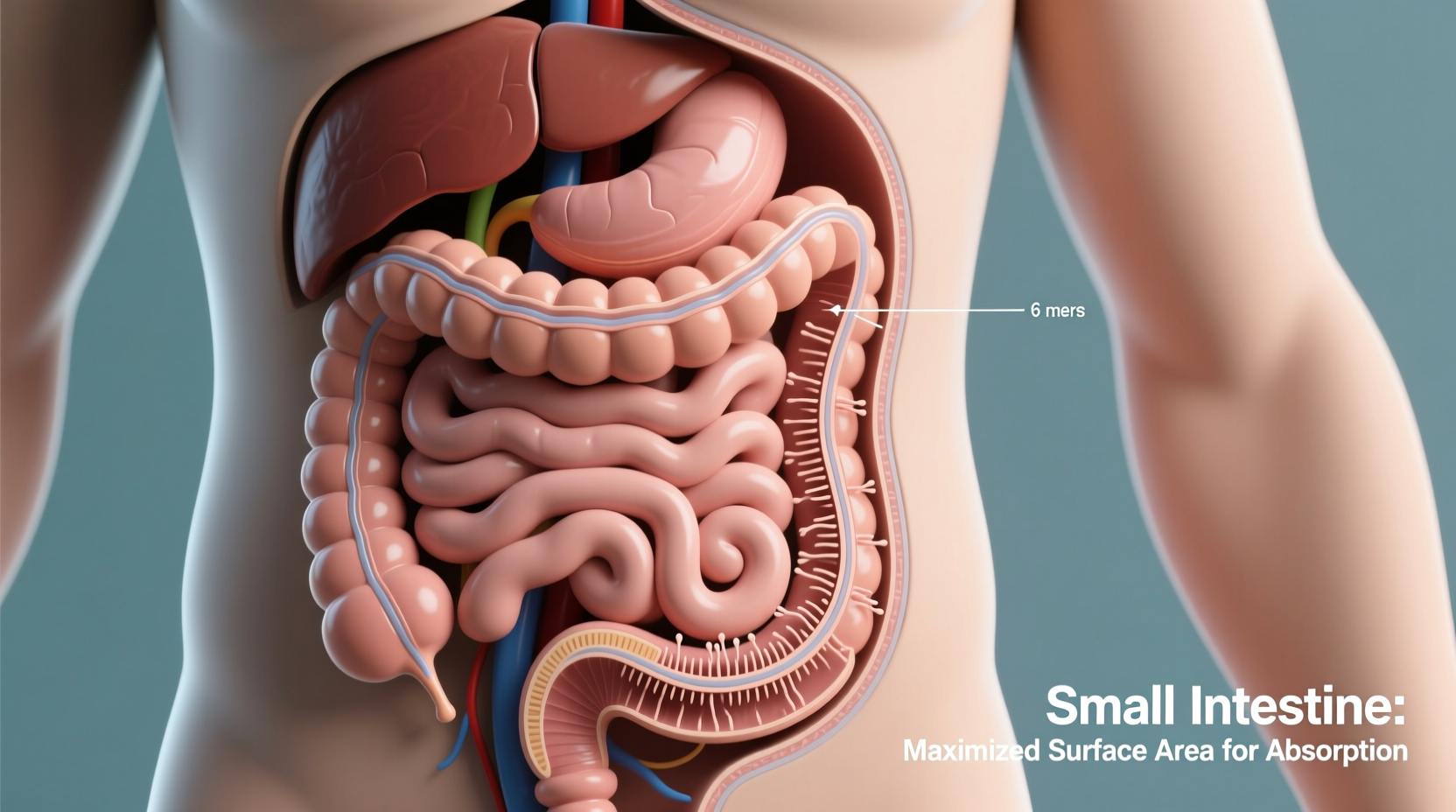

The small intestine is divided into three main sections: the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum. Each segment has a specialized role in processing food and absorbing nutrients.

- Duodenum: The shortest part, about 10 inches long, where chyme (partially digested food) mixes with bile from the liver and digestive enzymes from the pancreas.

- Jejunum: Makes up about two-fifths of the remaining length and is the primary site for nutrient absorption, especially carbohydrates, proteins, and fats.

- Ileum: The final and longest section, responsible for absorbing vitamin B12, bile salts, and any remaining nutrients before waste moves to the large intestine.

The internal surface area of the small intestine is vastly increased by structural adaptations: circular folds (plicae circulares), villi (tiny finger-like projections), and microvilli (microscopic extensions on epithelial cells). Together, these features increase the absorptive surface area to roughly the size of a tennis court—about 250 square meters. This massive surface area is only possible because of the organ's considerable length and intricate internal architecture.

Why Length Matters: Maximizing Nutrient Absorption

The primary reason the small intestine is so long is to provide sufficient time and space for complete digestion and nutrient absorption. When food enters the small intestine, it is not yet fully broken down. Enzymes and bile continue the chemical digestion process, turning macronutrients into absorbable molecules. These include amino acids from proteins, fatty acids and glycerol from fats, and simple sugars from carbohydrates.

If the small intestine were shorter, food would pass too quickly for optimal absorption. The extended transit time—typically 3 to 5 hours—allows for thorough interaction between nutrients and the absorptive lining. Without this duration, deficiencies in essential vitamins, minerals, and macronutrients would be common, leading to malnutrition even with adequate food intake.

“Evolution has optimized the small intestine’s length to balance efficient digestion with metabolic demands. Its size isn’t excessive—it’s precisely calibrated.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Gastrointestinal Physiologist, Harvard Medical School

Surface Area Amplification: How Structure Enhances Function

Length alone doesn’t explain the small intestine’s effectiveness. Its internal design multiplies functional capacity exponentially. Consider the following structural hierarchy:

- Circular folds: Wrinkles in the intestinal wall that slow the flow of chyme and increase surface contact.

- Villi: Millions of tiny projections that line the folds, each containing blood capillaries and a lacteal (lymph vessel) to transport absorbed nutrients.

- Microvilli: Cover the surface of epithelial cells, forming a “brush border” rich in digestive enzymes like lactase and sucrase.

This layered amplification allows the body to extract up to 90% of available nutrients from ingested food. For example, glucose molecules diffuse across the microvilli into the bloodstream within seconds of becoming available. Fats are packaged into chylomicrons and transported via the lymphatic system. The combination of length and microscopic complexity ensures that nearly every calorie consumed is utilized.

| Structural Feature | Function | Impact on Absorption |

|---|---|---|

| Circular folds | Slow food movement, increase surface area | Allows more time for enzyme action |

| Villi | Host capillaries and lacteals | Enable rapid uptake of nutrients into circulation |

| Microvilli | Contain digestive enzymes and transporters | Break down and absorb disaccharides and peptides |

Common Disorders That Affect Intestinal Efficiency

When the small intestine’s structure or function is compromised, even its impressive size may not prevent malabsorption. Conditions such as celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, and short bowel syndrome illustrate how vital length and integrity are to digestive health.

In celiac disease, gluten triggers an autoimmune response that flattens the villi, drastically reducing surface area. Patients often suffer from fatigue, weight loss, and nutrient deficiencies despite eating enough food. Similarly, surgical removal of portions of the small intestine—such as in short bowel syndrome—can severely limit nutrient absorption, requiring intravenous nutritional support.

Mini Case Study: Life After Bowel Resection

James, a 48-year-old construction worker, underwent surgery to remove 3 feet of his ileum due to Crohn’s-related damage. Post-surgery, he experienced persistent diarrhea, unintended weight loss, and low vitamin B12 levels. His doctor diagnosed him with partial malabsorption. Through dietary modifications—eating smaller, more frequent meals rich in easily digestible nutrients—and daily B12 supplementation, James gradually regained strength. His case underscores how even a modest reduction in intestinal length can disrupt homeostasis, emphasizing the organ’s natural length as a protective advantage.

Step-by-Step: How Food Travels Through the Small Intestine

Understanding the journey of food highlights why length is essential:

- Mouth to Stomach: Food is chewed, mixed with saliva, and swallowed. It enters the stomach, where acid and pepsin begin protein digestion.

- Entry into Duodenum: Chyme exits the stomach in small bursts, triggered by hormonal signals. Bile and pancreatic juice neutralize acidity and break down fats, proteins, and carbs.

- Journey Through Jejunum: Most nutrient absorption occurs here. Glucose, amino acids, and fatty acids cross into the bloodstream or lymph.

- Final Absorption in Ileum: Vitamin B12, bile salts, and leftover nutrients are absorbed. Bile salts are recycled back to the liver (enterohepatic circulation).

- Transition to Large Intestine: Undigested material, mostly fiber and water, moves into the colon for further processing and eventual elimination.

This entire process relies on the small intestine’s length to allow each phase to occur without rushing. Peristaltic waves gently push contents forward while segmentation contractions mix them with secretions—both mechanisms optimized over millions of years of evolution.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is it called the 'small' intestine if it’s longer than the large intestine?

The name refers to its diameter, not length. The small intestine is about 1 inch wide, while the large intestine is 3 inches wide, hence \"small\" in caliber despite being longer.

Can the small intestine regenerate its villi?

Yes, under normal conditions, the intestinal lining renews itself every 3 to 5 days. In celiac disease, villi can regrow once gluten is removed from the diet.

Does fasting affect small intestine function?

Short-term fasting does not impair function; in fact, it may enhance cellular repair processes like autophagy. However, prolonged malnutrition can lead to atrophy of the mucosal lining, reducing absorption efficiency.

Checklist: Supporting Your Small Intestine Health

- Eat a balanced diet rich in whole grains, lean proteins, and healthy fats

- Include probiotic-rich foods like yogurt or kefir to support gut flora

- Avoid excessive alcohol, which can damage the intestinal lining

- Stay hydrated to maintain proper mucus production and motility

- Manage stress through mindfulness or exercise—chronic stress can disrupt digestion

- Seek medical advice for persistent bloating, diarrhea, or unexplained weight loss

Conclusion: Respecting the Hidden Workhorse of Digestion

The human small intestine’s extraordinary length is a testament to evolutionary precision. Far from being an anatomical oddity, its size is fundamental to survival, enabling the extraction of energy and nutrients necessary for every bodily function. From the microscopic dance of microvilli to the coordinated muscular movements guiding food along its winding path, this organ exemplifies biological efficiency.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?