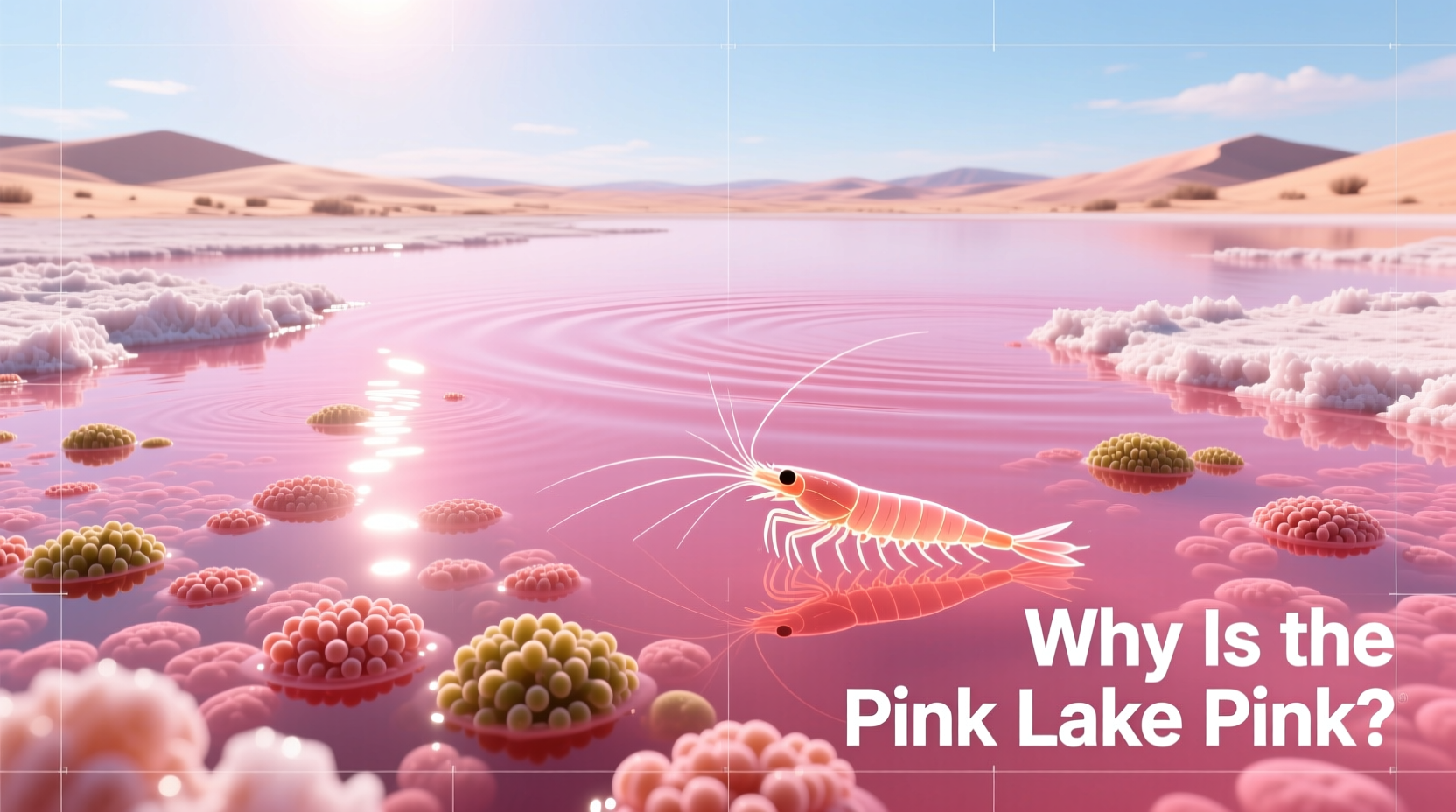

Pink lakes are among nature’s most surreal spectacles. Scattered across continents—from Australia to Senegal to Kazakhstan—these vividly colored bodies of water captivate travelers, scientists, and photographers alike. Their striking rose hue defies expectations of what a lake should look like, prompting the inevitable question: Why is the pink lake pink? The answer lies in a fascinating interplay of biology, chemistry, and climate. This article explores the scientific causes behind the phenomenon, revealing how microscopic life and environmental conditions transform ordinary saltwater into a natural masterpiece.

The Role of Microorganisms in Lake Coloration

The primary reason for the pink color of many saline lakes is the presence of specific microorganisms that produce pigments as part of their survival strategy. Two key players dominate this biological explanation: Dunaliella salina, a type of halophilic (salt-loving) green algae, and Haloquadratum walsbyi, a pink-hued archaea.

Dunaliella salina thrives in high-salinity environments where few other organisms can survive. Under stress—particularly from intense sunlight and limited nutrients—the algae produce large amounts of beta-carotene, a red-orange pigment also found in carrots and sweet potatoes. This antioxidant not only protects the algae from UV radiation but also gives the water a deep reddish or pink tint when present in high concentrations.

Simultaneously, certain halophilic bacteria and archaea contribute additional pigmentation. These extremophiles use bacteriorhodopsin, a light-sensitive protein that appears purple-pink, to generate energy through a process similar to photosynthesis. When both Dunaliella salina and pigmented archaea bloom together, their combined effect amplifies the pink appearance of the lake.

Environmental Conditions That Enable Pink Lakes

Pink lakes don’t form randomly. They require a precise combination of physical and chemical conditions to support the microbial blooms responsible for their color.

- High salinity: Most pink lakes are hypersaline, meaning they contain significantly more salt than seawater. This suppresses competition from other aquatic species, allowing specialized microbes to dominate.

- Abundant sunlight: Solar exposure promotes photosynthetic activity in algae and triggers pigment production as a protective response.

- Limited rainfall and high evaporation: Arid climates concentrate salts and nutrients, creating ideal breeding grounds for halophiles.

- Shallow depth: Shallow waters heat up quickly and allow sunlight to penetrate fully, enhancing microbial growth.

These conditions are commonly found in endorheic basins—closed drainage systems with no outflow—where water accumulates and evaporates over time, leaving behind concentrated minerals and salts.

Geographic Distribution and Notable Examples

Pink lakes exist on nearly every continent, though they’re most prevalent in arid coastal regions. Some of the most famous include:

| Lake Name | Location | Notable Features | Color Intensity Peak |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lake Hillier | Western Australia | Permanently pink; viewable from air | Year-round (most vibrant in summer) |

| Lake Retba (Lac Rose) | Senegal | Used for salt harvesting; swimmers apply shea butter | November–June (dry season) |

| Horseshoe Lake | South Australia | Part of Murray River system; seasonal color changes | Summer months |

| Lake Koyashskoe | Crimea, Ukraine | Produces brine shrimp; dries into salt crust | Late summer |

“Lake Hillier’s color remains stable even when the water is bottled. This suggests the pigment is chemically robust and biologically sustained.” — Dr. Naomi Parker, Extremophile Research Group, University of Adelaide

Myths and Misconceptions About Pink Lakes

Despite growing scientific understanding, several myths persist about pink lakes:

- Myth: The color comes from mineral deposits alone. While minerals like sodium chloride and magnesium sulfate are abundant, they are not inherently pink. The hue stems primarily from biological sources.

- Myth: All pink lakes are safe to swim in. High salinity makes some lakes buoyant and non-toxic, but others may harbor harmful bacteria or extreme pH levels. Always verify local safety guidelines.

- Myth: Pollution causes the pink color. In most cases, the phenomenon is entirely natural. Human activity can disrupt ecosystems, but it does not create the pink hue.

In fact, attempts to replicate pink lakes artificially have largely failed without introducing the correct microbial strains and maintaining strict environmental control.

Step-by-Step: How a Pink Lake Forms Over Time

The development of a pink lake is a gradual ecological process. Here’s a simplified timeline of how such a lake evolves under the right conditions:

- Water accumulation: Rain or groundwater collects in a closed basin with no river outflow.

- Evaporation begins: In hot, dry climates, water evaporates faster than it’s replenished, increasing salt concentration.

- Microbial colonization: Salt-tolerant algae and archaea migrate via wind, birds, or dust and begin to multiply.

- Pigment production: As salinity and sunlight intensify, microbes produce carotenoids and other pigments for protection.

- Bloom formation: Microbial populations explode during favorable seasons, turning the water visibly pink.

- Seasonal fluctuation: Color fades during rainy periods due to dilution, then returns as evaporation resumes.

Conservation Challenges and Ecotourism Impact

As pink lakes gain popularity on social media, visitation has surged—sometimes to unsustainable levels. Foot traffic, littering, and off-road vehicle use can damage fragile shorelines and disrupt microbial mats essential to the ecosystem.

In Western Australia, access to Lake Hillier is restricted to aerial views or guided boat tours to minimize impact. Similarly, in Senegal, local communities manage salt harvesting at Lake Retba sustainably, balancing economic needs with environmental preservation.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can you swim in a pink lake?

Yes, in some cases—like Lake Retba in Senegal—but with precautions. The high salt content makes swimming easy due to buoyancy, similar to the Dead Sea. However, prolonged exposure can dry the skin, so locals often coat themselves in shea butter. Always check local regulations and health advisories before entering.

Is the pink color harmful to humans or animals?

No, the pigments produced by Dunaliella salina and halophilic archaea are not toxic. In fact, beta-carotene is a nutritional supplement used in food and cosmetics. However, the extreme salinity can irritate eyes and open wounds, so caution is advised.

Do all pink lakes stay pink year-round?

No. While some, like Lake Hillier, maintain a consistent pink hue, many others fluctuate with seasons. During wet periods, dilution reduces salinity and microbial activity, causing the color to fade. The pink typically returns in dry, hot months.

Conclusion: A Natural Wonder Worth Understanding and Protecting

The pink lake phenomenon is a stunning example of how life adapts to extreme environments. Far from being a mere optical illusion or chemical anomaly, the color arises from complex biological processes fine-tuned by evolution. Understanding the science behind these lakes enriches our appreciation and underscores the importance of preserving them.

As climate change alters precipitation and evaporation patterns, some pink lakes may face existential threats. Rising sea levels could flood coastal basins, while prolonged droughts might dry others completely. Monitoring and protecting these sites ensures future generations can witness—and study—this remarkable natural wonder.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?