The plasma membrane is one of the most vital structures in a living cell, acting as a dynamic barrier between the internal environment of the cell and the external world. Its ability to regulate what enters and exits the cell is not random—it’s highly controlled. This precise control stems from its selective permeability, a defining characteristic that allows only certain molecules to pass through while blocking others. Without this property, cells could not maintain homeostasis, produce energy, or communicate effectively. Understanding why the plasma membrane is selectively permeable reveals fundamental principles of cellular biology and underscores the elegance of biological design.

The Structure Behind Selective Permeability

The foundation of selective permeability lies in the plasma membrane's molecular architecture. Composed primarily of a phospholipid bilayer, the membrane features two layers of phospholipids arranged so that their hydrophilic (water-attracting) heads face outward toward aqueous environments, while their hydrophobic (water-repelling) tails face inward, shielded from water.

This arrangement creates a semi-fluid barrier that naturally blocks large polar molecules and ions, which cannot easily dissolve in the hydrophobic core. Small nonpolar molecules like oxygen and carbon dioxide, however, diffuse freely across the membrane due to their solubility in lipids. This inherent property of the bilayer forms the first level of selectivity.

Beyond phospholipids, the membrane integrates proteins, cholesterol, and carbohydrates that further refine its filtering capabilities. Integral membrane proteins act as channels or carriers, facilitating the passage of specific substances such as glucose or sodium ions. Cholesterol modulates fluidity, ensuring the membrane remains flexible yet stable under varying conditions.

Mechanisms of Transport Across the Membrane

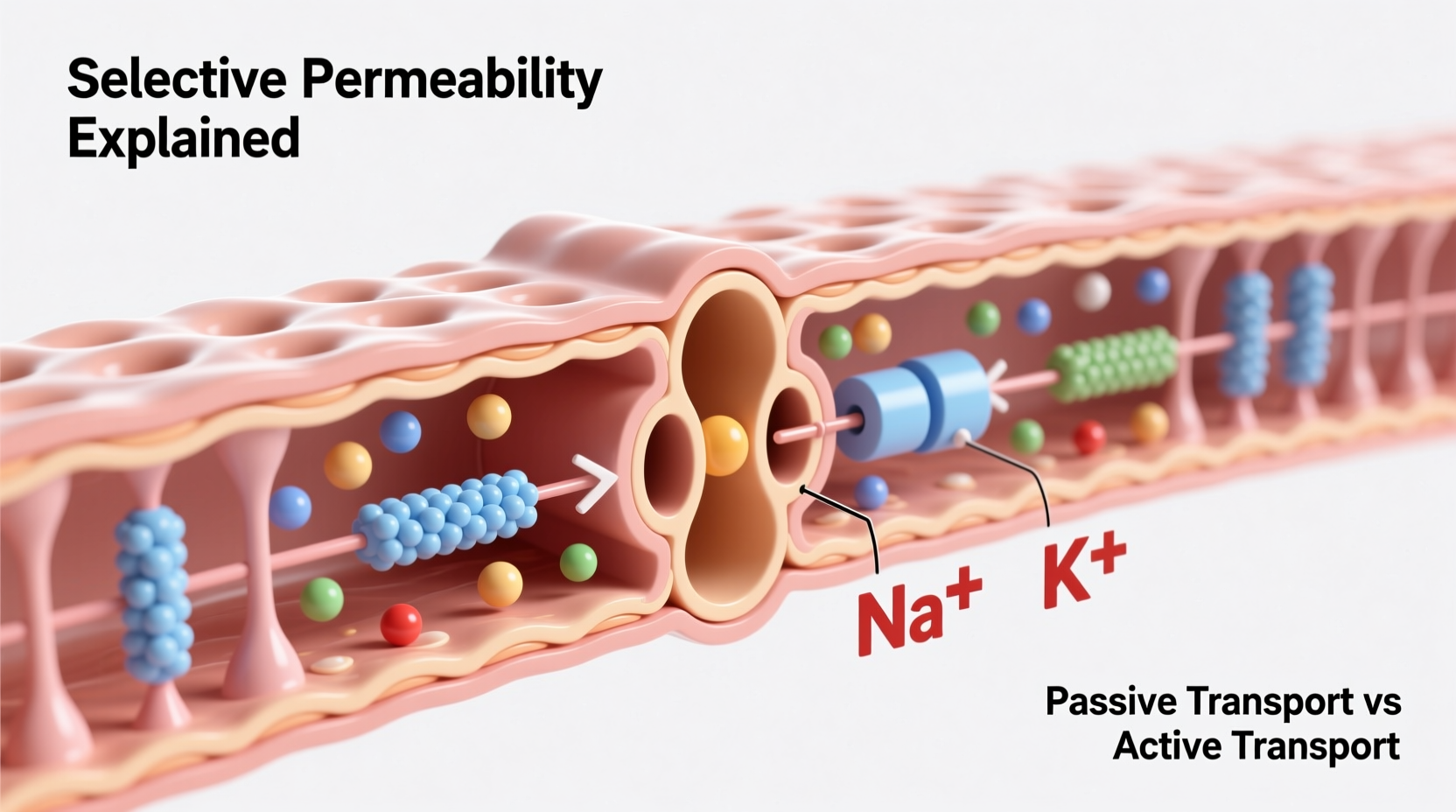

Selective permeability is enforced through multiple transport mechanisms, each suited to different types of molecules and cellular needs.

Passive Transport: Movement Without Energy

In passive transport, substances move down their concentration gradient—requiring no cellular energy (ATP). The main forms include:

- Simple diffusion: Small, nonpolar molecules (e.g., O₂, CO₂) slip directly through the lipid bilayer.

- Facilitated diffusion: Polar or charged molecules (e.g., glucose, ions) use channel or carrier proteins to cross.

- Osmosis: The diffusion of water through aquaporins or the lipid bilayer, driven by solute concentration differences.

Active Transport: Controlled Movement Against the Gradient

When substances must move against their concentration gradient, the cell invests energy. Active transport uses ATP-powered pumps, such as the sodium-potassium pump (Na⁺/K⁺ ATPase), to maintain critical ion balances essential for nerve impulses and nutrient uptake.

“Selective permeability isn’t just about blocking unwanted substances—it’s about enabling precision in signaling, metabolism, and survival.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Cell Biologist, University of California

Biological Significance of Selective Permeability

The consequences of selective permeability extend far beyond simple filtration. It enables essential physiological functions:

- Homeostasis: Cells maintain stable internal conditions despite fluctuating external environments. For example, kidney cells regulate water and salt balance through selective reabsorption.

- Nutrient Uptake: Glucose enters cells via facilitated diffusion using GLUT transporters, ensuring energy availability without uncontrolled influx.

- Toxin Exclusion: Harmful substances, including many drugs and metabolic waste products, are prevented from accumulating inside the cell.

- Cell Signaling: Ion gradients established by selective transport allow action potentials in neurons, forming the basis of nervous system communication.

Disruption of selective permeability can lead to cellular dysfunction or death. For instance, some antibiotics like polymyxin disrupt bacterial membranes, increasing permeability and causing leakage of essential ions—a lethal effect for microbes but not human cells, thanks to structural differences.

Real-World Example: Cystic Fibrosis and Membrane Dysfunction

A compelling illustration of selective permeability’s importance is seen in cystic fibrosis (CF), a genetic disorder affecting chloride ion transport. In healthy individuals, the CFTR (cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator) protein acts as a gated channel, allowing chloride ions to exit epithelial cells, which in turn draws water into mucus, keeping it fluid.

In CF patients, mutations in the CFTR gene impair this channel function. As a result, chloride cannot pass through efficiently, disrupting osmotic balance. Mucus becomes thick and sticky, particularly in the lungs and pancreas, leading to chronic infections and digestive issues. This case underscores how a single defect in selective permeability can cascade into systemic disease.

Factors Influencing Membrane Permeability

Several factors determine how permeable a membrane is to specific substances:

| Factor | Effect on Permeability | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Size | Smaller molecules diffuse more easily | O₂ crosses rapidly; proteins do not |

| Polarity | Nonpolar molecules pass through lipids | Fatty acids enter easily; amino acids require carriers |

| Charge | Ions face strong resistance without channels | Na⁺, K⁺, Ca²⁺ rely on ion channels or pumps |

| Temperature | Higher temps increase fluidity and diffusion | Metabolic rates rise with warmth |

| Cholesterol Content | Stabilizes fluidity—prevents extremes | Animal cells remain functional across temperatures |

Actionable Checklist: Key Concepts to Remember

To fully grasp why the plasma membrane is selectively permeable, consider the following checklist:

- Recognize that the phospholipid bilayer blocks most polar and charged substances by default.

- Identify transport proteins as gatekeepers for specific molecules like glucose and ions.

- Understand the role of passive vs. active transport in maintaining concentration gradients.

- Appreciate how osmosis affects cell volume and turgor pressure.

- Link membrane composition (e.g., cholesterol, protein diversity) to functional adaptability.

- Relate defects in membrane transport to real diseases like cystic fibrosis or hypertension.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why can't ions like Na⁺ and K⁺ diffuse directly through the membrane?

Ions are both charged and highly polar, making them insoluble in the hydrophobic interior of the lipid bilayer. They require specialized ion channels or carrier proteins to cross, ensuring precise regulation of electrical and chemical gradients.

How do cells absorb large molecules if the membrane is selectively permeable?

Cells use endocytosis—engulfing large particles or fluids by wrapping the membrane around them to form vesicles. This process bypasses the need for direct diffusion and maintains control over intake.

Does selective permeability vary between cell types?

Yes. Specialized cells express different sets of membrane proteins tailored to their function. For example, intestinal epithelial cells have abundant glucose transporters, while neurons are rich in voltage-gated ion channels.

Conclusion: The Intelligence of Cellular Boundaries

The plasma membrane’s selective permeability is not a passive filter but an intelligent, responsive interface. It balances freedom and restriction, allowing life-sustaining processes to occur with remarkable efficiency. From the silent diffusion of oxygen to the precisely timed opening of ion channels, every interaction at the membrane contributes to the coherence of cellular life.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?