The United States of America—a nation known globally by its full name, shortened to “America” in casual and formal contexts alike. But how did a country named after union and independence come to bear a name derived not from its founders, geography, or indigenous roots, but from an Italian explorer? The answer lies in a curious blend of exploration, cartography, and historical accident.

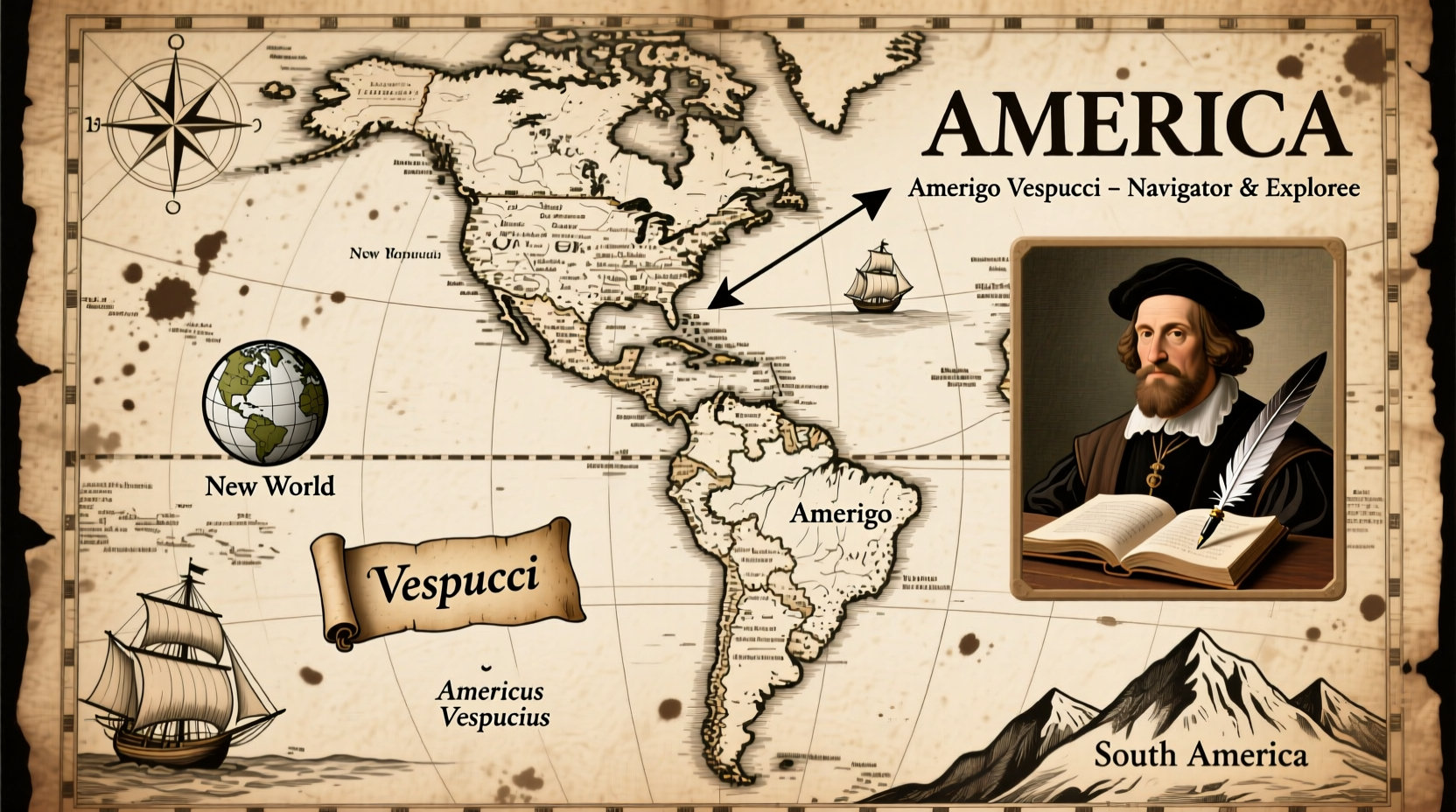

The naming of the Americas—both North and South—is one of the most fascinating anomalies in geographical history. Despite Christopher Columbus’s famed 1492 voyage, it was not he who lent his name to the continents. Instead, credit (or controversy) goes to Amerigo Vespucci, a navigator whose writings helped reshape Europe’s understanding of the New World.

The Man Behind the Name: Who Was Amerigo Vespucci?

Born in Florence in 1454, Amerigo Vespucci was a merchant, navigator, and astronomer who participated in early exploratory voyages along the eastern coast of South America in the late 1490s. Unlike Columbus, who believed until his death that he had reached Asia, Vespucci proposed that the lands discovered west of the Atlantic were part of a previously unknown “New World.”

In letters attributed to him—most notably Mundus Novus (circa 1503)—Vespucci described vast territories and peoples distinct from Asian civilizations. These accounts circulated widely across Europe and influenced scholars eager to map the expanding world.

“We have discovered a continent much more extensive than India or Cathay, populous with innumerable people and animals.” — Attributed to Amerigo Vespucci in *Mundus Novus*

His insights suggested these lands were not islands off Asia but entirely new continents—an idea that gained traction among European intellectuals.

The Role of Martin Waldseemüller: A Cartographer’s Decision

The pivotal moment in the naming of America came in 1507, when German cartographer Martin Waldseemüller published a world map titled Universalis Cosmographia. Working at the Saint-Dié monastery in present-day France, Waldseemüller and his colleagues sought to incorporate the latest geographic knowledge into a comprehensive map.

Inspired by Vespucci’s descriptions, Waldseemüller labeled the southern portion of the newly recognized landmass “America”—a Latinized feminine form of “Amerigo,” meaning “land of Amerigo.” He applied the name specifically to what is now South America, honoring Vespucci as the first to identify it as a separate continent.

This was no minor footnote. The map was revolutionary for its time, introducing the concept of two vast continents separated from Asia by ocean. It also included a small booklet, Cosmographiae Introductio, which explicitly justified the naming:

“Since both Asia and Africa received their names from women, I see no reason why anyone should rightly object to calling this [new] land after Americus, its discoverer, a man of acute genius, America.”

Though Waldseemüller later expressed doubt about crediting Vespucci over Columbus, the name had already taken root. Once printed and distributed, “America” began appearing on maps across Europe.

How \"America\" Expanded to Include North America

Initially, “America” referred only to South America. However, as exploration continued and the full scope of the Western Hemisphere became clearer, cartographers began applying the name to the northern continent as well. By the mid-16th century, maps increasingly depicted both North and South America under the broader label “America.”

When British colonies formed along the eastern seaboard of North America, they were still considered part of “America” in the continental sense. After declaring independence in 1776, the new nation officially adopted the name “United States of America”—a formal recognition of its place within the larger landmass.

Over time, “America” became shorthand not just for the continent, but specifically for the United States—a usage that persists today, despite occasional criticism from residents of other American nations.

Timeline: Key Moments in the Naming of America

The evolution of the name spans decades of exploration, debate, and dissemination. Here’s a chronological overview:

- 1492: Christopher Columbus reaches the Bahamas, believing he has arrived in Asia.

- 1499–1502: Amerigo Vespucci joins expeditions to the coast of South America; writes detailed accounts of a “New World.”

- 1503: Vespucci’s letter Mundus Novus is published, spreading the idea of a new continent.

- 1507: Martin Waldseemüller releases his world map, labeling South America as “America.”

- 1538: Gerardus Mercator applies “America” to both northern and southern continents on his maps.

- 1776: The Thirteen Colonies adopt “United States of America” as their official name upon independence.

- 1800s–Present: “America” becomes synonymous with the U.S. in common usage, especially in political and cultural discourse.

Controversy and Criticism: Did Vespucci Deserve the Honor?

The naming of America after Vespucci has long been debated. Critics argue that Columbus made the initial transatlantic crossing, while Indigenous peoples inhabited the continents for millennia before any European arrival. Others question whether Vespucci even wrote the letters attributed to him, suggesting they may have been embellished or forged by publishers.

Historian Felipe Fernández-Armesto notes:

“The name ‘America’ is a cartographic accident compounded by marketing. Vespucci didn’t claim to have discovered a continent, but others projected that idea onto him—and the name stuck.”

Moreover, Indigenous civilizations like the Aztecs, Maya, Inca, and countless Native American nations had rich names for their homelands. Yet none entered European nomenclature. The imposition of “America” reflects the colonial mindset of the era—one that prioritized European discovery narratives over existing cultures.

FAQ: Common Questions About the Name “America”

Did Amerigo Vespucci know the continents were named after him?

There is no definitive evidence that Vespucci knew about the naming before his death in 1512. The 1507 map was widely distributed, but whether it reached him remains uncertain.

Why wasn’t the continent named Columbia instead?

While “Columbia” was proposed and used poetically (e.g., in “District of Columbia”), it never replaced “America” in official cartography. By the time alternative names emerged, “America” was already entrenched in maps and scholarly texts.

Is it incorrect to call the U.S. “America”?

Linguistically, no—“America” refers to the continents, and the U.S. is part of it. However, in international contexts, using “the U.S.” is more precise and respectful of other American nations.

Do’s and Don’ts: Using the Term “America” Respectfully

| Do | Don't |

|---|---|

| Use “the U.S.” when referring specifically to the United States. | Assume “America” refers only to the United States. |

| Acknowledge that “America” includes North, Central, and South America. | Say “you’re not from America” to someone from Mexico or Argentina. |

| Recognize the Indigenous histories predating European naming. | Treat the name “America” as the original or only legitimate designation. |

Real Example: A Diplomatic Misunderstanding

In 2019, a U.S. official gave a speech referring to “America’s achievements in space exploration,” listing NASA milestones. While factually accurate, audiences in Latin America interpreted the phrasing as erasing their own scientific contributions and national identities. Social media responses highlighted the phrase “We are also America,” emphasizing regional inclusivity.

This incident illustrates how language shapes perception. What may seem like neutral terminology in one context can carry exclusionary undertones in another.

Conclusion: Understanding the Legacy of a Name

The name “America” is more than a label—it’s a historical artifact reflecting exploration, ambition, and the power of ideas to endure beyond their origins. Coined for a continent based on a single cartographer’s tribute, it evolved into a national identity for the United States, even as it overlooks deeper histories and broader geographies.

Knowing the origin of “America” doesn’t change everyday usage, but it deepens our awareness of how names shape belonging, memory, and perspective. Whether you're writing a paper, traveling abroad, or engaging in conversation, recognizing the full story behind “America” fosters greater clarity and respect.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?