Tuna is a staple in many diets around the world, prized for its rich flavor, high protein content, and heart-healthy omega-3 fatty acids. However, beneath its nutritional benefits lies a hidden concern: mercury contamination. While not all tuna carries the same risk, certain types—especially larger species—can contain levels of mercury that raise serious health questions. Understanding why tuna accumulates mercury, who is most at risk, and how to consume it safely is essential for making informed dietary choices.

How Mercury Enters the Food Chain

Mercury is a naturally occurring element released into the environment through volcanic activity, weathering of rocks, and human activities like coal burning and industrial processes. Once in waterways, inorganic mercury is converted by bacteria into methylmercury—a highly toxic organic form that easily accumulates in living organisms.

Fish absorb methylmercury directly from water through their gills and indirectly by eating contaminated prey. Because methylmercury binds strongly to proteins in muscle tissue, it doesn’t flush out easily. Instead, it bioaccumulates—meaning concentrations increase over time as the fish grows older and consumes more contaminated food.

Larger predatory fish like tuna sit near the top of the marine food chain. They eat smaller fish, which have already absorbed mercury, leading to biomagnification—the process where toxin levels become exponentially higher at each successive level of the food chain.

“Predatory fish such as tuna can carry mercury levels millions of times higher than the surrounding water.” — Dr. Jane Harper, Environmental Toxicologist, NOAA

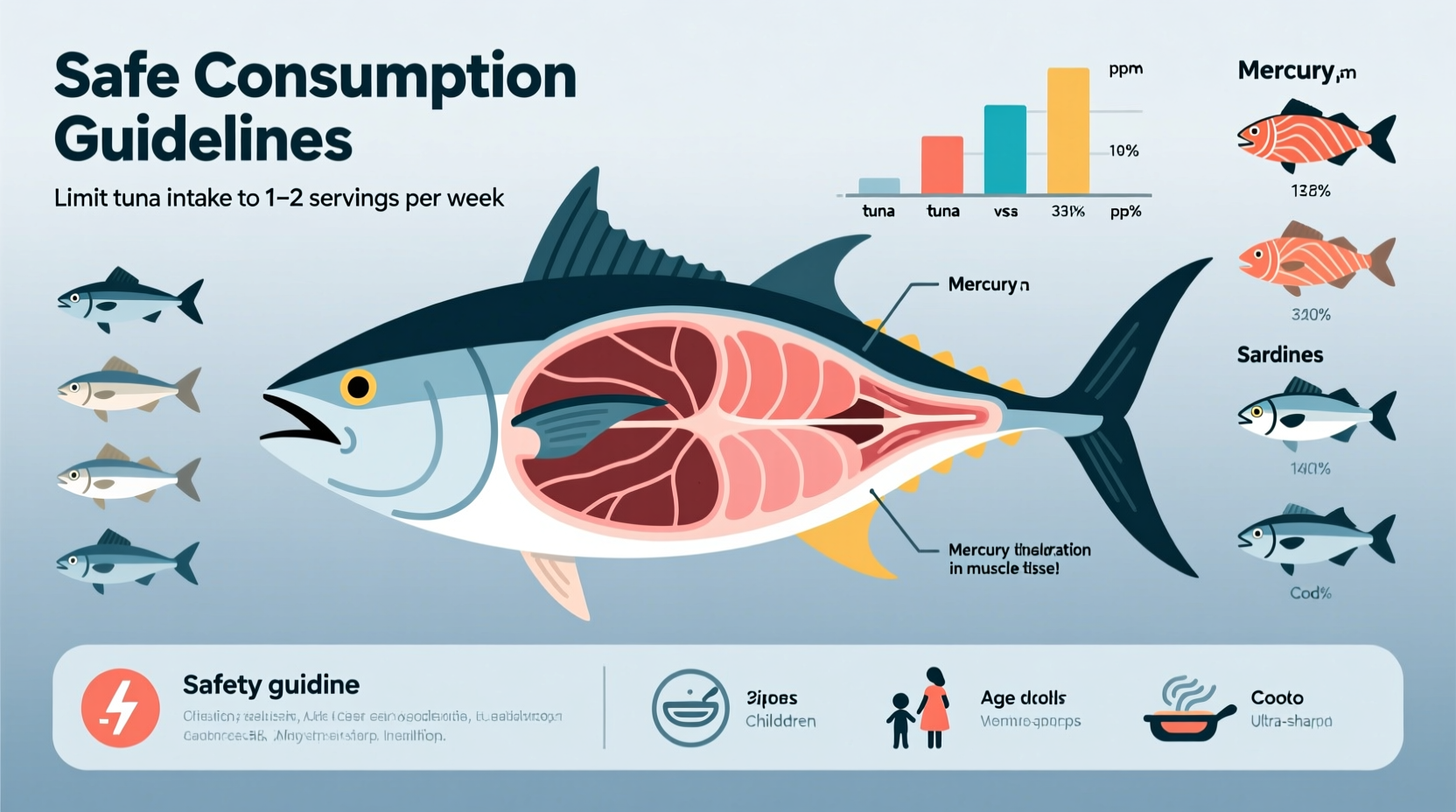

Types of Tuna and Their Mercury Levels

Not all tuna is created equal when it comes to mercury content. The size, lifespan, and diet of the species play a major role. Here’s a comparison of common tuna varieties:

| Type of Tuna | Average Mercury Level (ppm) | Recommended Consumption |

|---|---|---|

| Light Canned Tuna (skipjack) | 0.12 ppm | Safer for regular consumption; up to 2–3 servings/week |

| Albacore (White) Tuna | 0.32 ppm | Moderate risk; limit to 1 serving/week |

| Yellowfin Tuna | 0.35 ppm | Limit intake, especially for pregnant women |

| Bigeye Tuna | 0.68 ppm | High mercury; avoid frequent consumption |

| Bluefin Tuna | 0.75+ ppm | Highest risk; best consumed rarely or avoided |

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) categorizes fish into “Best Choices,” “Good Choices,” and “Choices to Avoid” based on mercury levels. Light canned tuna falls under “Best Choices,” while albacore and yellowfin are “Good Choices.” Bigeye and bluefin tuna often fall into the “Avoid” category for sensitive populations.

Who Is Most at Risk?

While mercury poses some risk to everyone, certain groups are far more vulnerable due to developmental or physiological factors:

- Pregnant and breastfeeding women: Methylmercury crosses the placenta and can impair fetal brain development, potentially leading to cognitive delays, motor skill deficits, and learning disabilities.

- Young children: Developing nervous systems are highly sensitive to neurotoxins. High mercury exposure during early childhood may affect memory, attention, and language acquisition.

- Women planning pregnancy: Mercury can linger in the body for over a year, so pre-pregnancy exposure matters.

- Frequent seafood consumers: People who eat fish daily or multiple times per week may accumulate unsafe levels over time, even if individual meals seem low-risk.

The FDA and EPA jointly advise that pregnant women, those trying to conceive, and young children avoid high-mercury fish entirely and limit intake of moderate-mercury species.

Safe Consumption Guidelines

You don’t need to eliminate tuna from your diet—just make smarter choices. Follow these steps to minimize mercury risk while still benefiting from tuna’s nutritional profile:

- Choose lower-mercury options: Stick to light canned tuna (skipjack) instead of albacore or fresh bigeye.

- Control portion sizes: A standard serving is about 3–4 ounces (85–115 grams). Limit albacore to once a week.

- Vary your seafood: Don’t rely solely on tuna. Rotate in low-mercury fish like salmon, sardines, trout, and shrimp.

- Check sourcing: Some brands test for contaminants. Look for third-party certifications like ConsumerLab or NSF International.

- Monitor local advisories: If you eat locally caught fish, consult state health department guidelines, as mercury levels can vary by region.

Mini Case Study: A Family’s Dietary Shift

The Rivera family loved tuna salad sandwiches—three times a week. When Maria, who was six months pregnant, learned about mercury risks during a prenatal visit, she consulted a dietitian. Testing revealed her mercury levels were elevated but not dangerous. Together, they revised the family’s meal plan: swapping two tuna meals for canned salmon and whitefish. Within three months, follow-up tests showed a 40% drop in her mercury levels, and the family discovered they enjoyed the new variety just as much.

Debunking Common Myths

Several misconceptions persist about mercury in fish:

- Myth: “Canned tuna is always safe.”

Truth: While light canned tuna is relatively low in mercury, albacore (“white”) tuna is significantly higher. - Myth: “Cooking removes mercury.”

Truth: Mercury is bound in the flesh of the fish and cannot be cooked, washed, or trimmed away. - Myth: “One high-mercury meal won’t hurt.”

Truth: Occasional exposure is usually not harmful, but regular consumption builds up over time, especially in vulnerable groups.

FAQ

Can I eat sushi with tuna safely?

Yes, but with caution. Many sushi-grade tuna varieties—especially bigeye and bluefin—are high in mercury. Opt for skipjack or ask what type is being served. Limit tuna sushi to once a month, particularly if you're pregnant or feeding children.

How long does mercury stay in the body?

Methylmercury has a half-life of about 50 days in adults, meaning it takes roughly 100–120 days to eliminate most of it. However, complete clearance can take up to a year, and it persists longer in blood during pregnancy.

Is there mercury-free tuna?

No tuna is completely mercury-free due to ocean contamination. However, younger, smaller species like skipjack have minimal levels and are considered safe for moderate consumption.

Action Checklist for Safer Tuna Consumption

- ✔ Identify the type of tuna you’re buying—prefer skipjack over albacore.

- ✔ Limit albacore or fresh tuna to no more than once per week.

- ✔ Avoid bigeye and bluefin tuna, especially if pregnant or feeding children.

- ✔ Diversify your seafood intake with low-mercury alternatives.

- ✔ Keep track of weekly fish servings using a food journal or app.

Conclusion

Tuna remains a nutritious and convenient source of lean protein and omega-3s, but its position in the marine food chain makes it prone to mercury accumulation. By understanding which types carry higher risks and adjusting your habits accordingly, you can continue enjoying tuna without compromising your health. The key is awareness, moderation, and smart substitution. Whether you're a parent, expecting a child, or simply a seafood lover, informed choices today lead to better long-term well-being.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?