Water is one of the most abundant and essential substances on Earth, vital not only for sustaining life but also for countless chemical and biological processes. Often referred to as the \"universal solvent,\" water has an unmatched ability to dissolve more substances than any other liquid. This remarkable characteristic stems from its unique molecular structure and physical properties. Understanding why water earns this title requires exploring its polarity, hydrogen bonding, and interactions with various solutes. From cellular biology to environmental science, water’s role as a solvent underpins nearly every natural system.

The Molecular Basis of Water’s Solvent Power

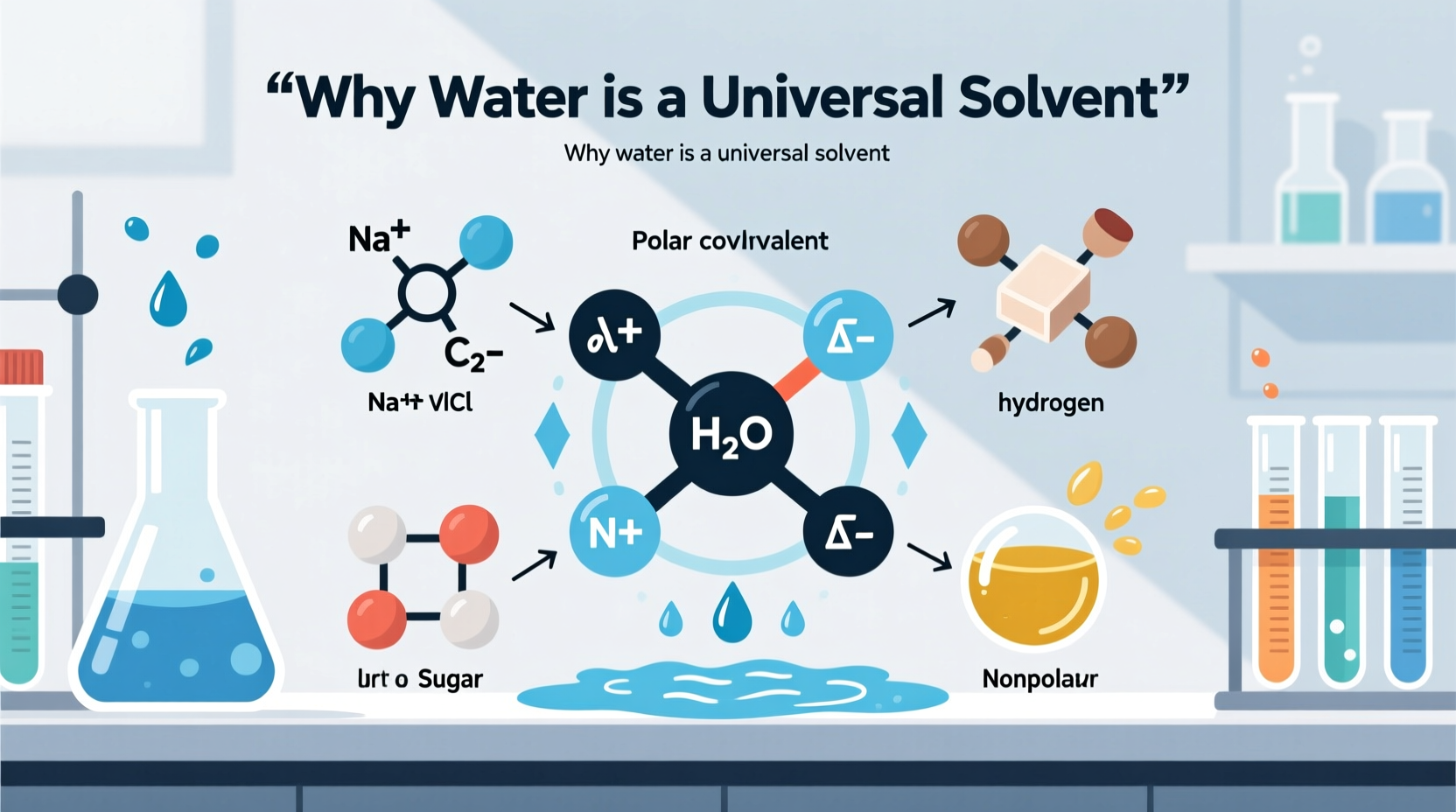

At the heart of water’s effectiveness as a solvent lies its molecular composition: two hydrogen atoms bonded to one oxygen atom (H₂O). The oxygen atom is highly electronegative, meaning it attracts electrons more strongly than hydrogen. This creates an uneven distribution of charge across the molecule—oxygen carries a partial negative charge, while the hydrogens carry partial positive charges. As a result, water is a polar molecule.

This polarity enables water to interact electrostatically with other charged or polar substances. When ionic compounds like table salt (NaCl) are introduced into water, the positively charged sodium ions (Na⁺) are attracted to the oxygen end of water molecules, while the negatively charged chloride ions (Cl⁻) are drawn to the hydrogen ends. These interactions pull the ions apart, effectively dissolving the compound.

Hydrogen Bonding and Its Role in Solubility

Beyond simple polarity, water forms hydrogen bonds—weak but significant attractions between the hydrogen atom of one water molecule and the oxygen atom of another. Each water molecule can form up to four hydrogen bonds, creating a dynamic network that enhances its solvent capabilities.

Hydrogen bonding allows water to surround dissolved particles effectively, stabilizing them in solution through hydration shells. For example, when glucose—a polar covalent molecule—enters water, its hydroxyl (-OH) groups form hydrogen bonds with surrounding water molecules, allowing it to disperse evenly throughout the liquid.

This same property contributes to water’s high surface tension, cohesion, and specific heat—all of which indirectly support its function as a solvent in biological systems where temperature stability and structural integrity are crucial.

“Water’s polarity and hydrogen bonding capacity make it the single most versatile solvent in nature.” — Dr. Linda Chen, Biochemist and Environmental Scientist

Why Is Water Called the Universal Solvent?

The term “universal solvent” does not mean that water dissolves everything—it doesn’t dissolve nonpolar substances like fats, waxes, or many plastics. However, it dissolves more types of materials and in greater quantities than any other liquid known, earning it this distinguished label.

In living organisms, water transports nutrients, minerals, and waste products by dissolving them and carrying them through blood, sap, or intracellular fluids. In the environment, rainwater leaches minerals from rocks and soil, contributing to nutrient cycling. Even in industrial applications, water serves as a primary medium for chemical reactions due to its safety, availability, and solvation efficiency.

The universality of water as a solvent is especially evident in biochemistry. Enzymes, proteins, DNA, and metabolic intermediates all rely on aqueous environments to function properly. Without water’s ability to dissolve and stabilize these complex molecules, life as we know it would not exist.

Factors Affecting Water’s Solvent Efficiency

While water is inherently a powerful solvent, several factors influence how well it dissolves different substances:

- Temperature: Higher temperatures increase molecular motion, speeding up the dissolution process. Warm water dissolves sugar faster than cold water.

- Pressure: Pressure has minimal effect on solids and liquids but significantly enhances gas solubility (e.g., carbon dioxide in soda).

- Particle Size: Smaller solute particles have greater surface area, leading to faster dissolution.

- Agitation: Stirring or shaking helps distribute solute particles and prevents saturation at localized sites.

| Factor | Effect on Solubility | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature ↑ | Solubility of solids ↑, gases ↓ | Sugar dissolves better in hot tea |

| Pressure ↑ | Gases ↑, solids/liquids no change | Carbonation under high pressure |

| Polarity Match | Polar/polar = high solubility | Salt dissolves; oil does not |

| Surface Area ↑ | Dissolution rate ↑ | Granulated sugar vs. cube |

Real-World Example: Kidney Function and Water’s Solvent Role

A compelling illustration of water’s importance as a solvent occurs in human physiology—specifically, in kidney function. The kidneys filter approximately 180 liters of blood daily, removing metabolic waste such as urea, excess ions, and toxins. These substances must be soluble in water to be processed and excreted in urine.

When someone becomes dehydrated, the concentration of solutes in the blood increases. This reduces the solvent capacity of water in the bloodstream, impairing the kidneys’ ability to flush out waste efficiently. Over time, this can lead to kidney stones—crystalline deposits formed when normally soluble calcium and oxalate compounds precipitate due to low water volume.

This case underscores a critical point: water’s value isn't just in being present, but in maintaining sufficient quantity to act as an effective solvent. Proper hydration ensures that water continues to perform its biological duties without compromise.

Practical Tips for Leveraging Water’s Solvent Properties

- Always use clean, contaminant-free water when preparing solutions to avoid unwanted chemical interactions.

- For household cleaning, mix water with mild detergents—its solvent power enhances their ability to lift dirt and grease.

- In gardening, ensure consistent watering so soil nutrients remain dissolved and accessible to plant roots.

- Avoid mixing water with nonpolar substances unless an emulsifier (like soap) is used to bridge the gap.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can water dissolve metals?

Pure elemental metals like iron or copper do not dissolve directly in water. However, some metals react with water to form soluble ionic compounds. For example, sodium metal reacts violently with water to produce sodium hydroxide, which then dissolves. Most common metal dissolution occurs through oxidation (rusting), where iron combines with oxygen and water to form soluble iron oxides.

Why doesn’t water dissolve oil?

Oil consists of nonpolar hydrocarbon chains that lack electrical charges. Since water is polar, there is no favorable interaction between the two. Instead, water molecules hydrogen-bond tightly with each other, excluding oil molecules in a process called hydrophobic effect. To mix them, an emulsifying agent like soap is required to reduce surface tension and create micelles.

Is distilled water a better solvent than tap water?

Distilled water is purer and lacks dissolved minerals and ions found in tap water, making it more chemically stable. However, its solvent power isn’t inherently stronger. In fact, because it contains fewer ions, it may temporarily hold less buffering capacity. For laboratory or medical uses, distilled water is preferred to prevent interference from impurities.

Conclusion: Embracing Water’s Unique Capabilities

Water’s status as the universal solvent is rooted in its elegant molecular design—polar structure, hydrogen bonding, and versatility in interacting with diverse substances. Whether facilitating photosynthesis in plants, enabling nerve conduction in animals, or supporting industrial synthesis, water’s solvent properties are indispensable.

Understanding these principles empowers better decisions in health, cooking, cleaning, agriculture, and environmental stewardship. By respecting water’s role—not just as a drink but as a dynamic participant in chemical processes—we gain deeper appreciation for its quiet yet profound influence on everyday life.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?