In the animal kingdom, few things are as oddly specific—and strangely captivating—as the cube-shaped droppings of the wombat. Unlike any other mammal, wombats produce feces with distinct geometric edges, almost as if carved by precision tools. For years, scientists were baffled. How could a soft digestive tract create such rigidly defined cubes? And more importantly, why would evolution favor square scat? The answers lie at the intersection of biomechanics, evolutionary adaptation, and gastrointestinal physics.

This unusual trait isn’t just a quirky factoid; it reveals deeper insights into how anatomy shapes behavior and survival. By studying wombat digestion, researchers have uncovered principles that may even influence engineering design. Let’s explore the science behind one of nature’s most enigmatic outputs.

The Wombat’s Digestive Uniqueness

Wombats are burrowing marsupials native to Australia, known for their stocky build, powerful claws, and nocturnal habits. They consume large quantities of fibrous plant material—mainly grasses, roots, and bark—which requires an extended digestive process. Their gut can take up to 14 days to fully break down food, one of the slowest digestion rates among mammals. This prolonged retention allows maximum nutrient extraction from low-quality vegetation.

But it's not just the duration of digestion that sets them apart—it's the final form of waste. Wombats excrete between 80 to 100 pellets per night, each measuring about 1–2 centimeters on a side. These aren't merely angular; they're true cubes, complete with flat faces and sharp corners. No other animal produces feces with such geometric consistency.

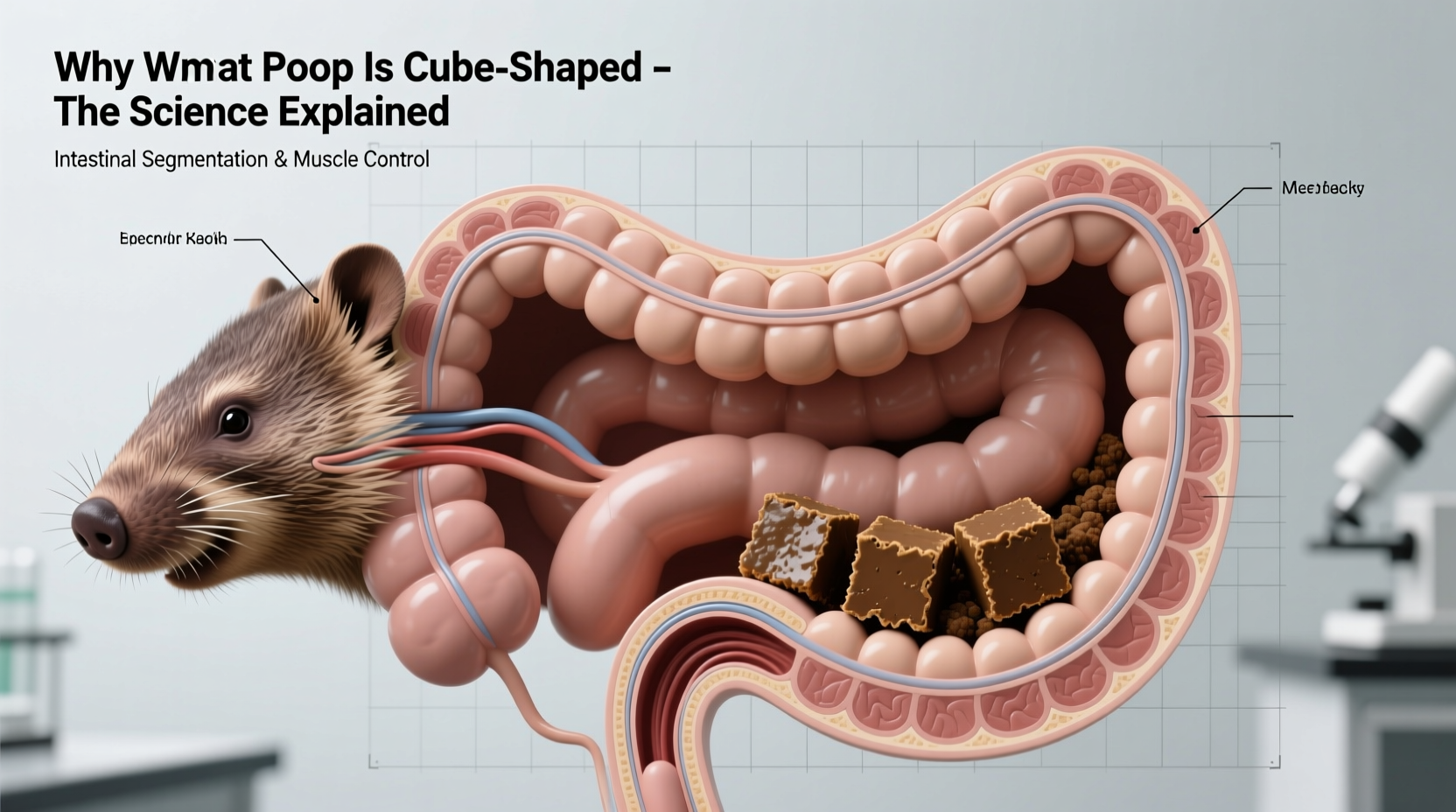

How Does a Soft Intestine Make Cubes?

For decades, scientists assumed the rectum must contain some rigid mold-like structure to shape the feces. However, dissections revealed no hard tissues or internal templates. The mystery deepened until researchers at Georgia Tech conducted a groundbreaking study using wombat intestines obtained post-mortem from roadkill specimens.

Using inflated balloons to simulate stool movement through the intestinal tract, the team discovered something remarkable: the elasticity of the intestinal wall varies dramatically along its length. In most animals, the gut expands uniformly. But in wombats, the last 8% of the intestine—the distal colon—has alternating stiff and flexible regions.

These variations cause uneven compression of drying fecal matter. As the waste moves forward, the stiffer sections contract less, forming flat surfaces, while the more elastic areas squeeze inward slightly, creating defined edges. Over multiple contractions, these differential pressures sculpt the pellet into a cube. It’s not a mold—it’s a mechanical origami powered by muscle and tissue variation.

“Nature doesn’t need a 3D printer to make cubes. It uses variable stiffness in soft tissues to sculpt geometry over time.” — Dr. Patricia Yang, Biomechanics Researcher, Georgia Institute of Technology

Why Evolve Square Poop? The Evolutionary Advantage

At first glance, cube-shaped poop seems like an evolutionary oddity with no clear benefit. But when viewed through the lens of behavior and ecology, the purpose becomes apparent: communication.

Wombats are largely solitary and territorial. They mark their domain using scent cues, primarily through urine and feces. Rather than burying or scattering droppings, wombats often stack them atop rocks, logs, or raised mounds—natural \"billboards\" visible to others. Round pellets would roll off these perches, especially on sloped surfaces. Cubes, however, stay put.

This stability ensures that olfactory signals remain in place longer, increasing the effectiveness of territorial marking. Additionally, stacking cubic droppings may amplify scent dispersion, allowing chemical messages to linger and broadcast more efficiently across the landscape.

Key Functions of Cube-Shaped Feces

- Prevents rolling: Maintains position on elevated or uneven surfaces.

- Facilitates stacking: Enables creation of visual and olfactory markers.

- Extends signal duration: Stable placement means scents degrade slower.

- Reduces re-marking frequency: Less need to replenish displaced droppings.

Scientific and Engineering Implications

Beyond zoology, the wombat’s natural cube-making ability has inspired cross-disciplinary interest. Engineers and material scientists see potential applications in soft robotics and manufacturing processes involving non-uniform molding without rigid forms.

Traditional methods for shaping soft materials require external molds, which can be costly and inefficient. The wombat’s method demonstrates how controlled elasticity within a single chamber can generate complex geometries—offering a blueprint for designing adaptive extrusion systems.

| Feature | Typical Mammal Poop | Wombat Poop |

|---|---|---|

| Shape | Cylindrical, rounded | Cube-like with flat faces |

| Drying Process | Uniform contraction | Non-uniform compression due to variable wall stiffness |

| Territorial Use | Buried or scattered | Stacked visibly on elevated surfaces |

| Mechanical Formation | Smooth muscular peristalsis | Alternating stiff/flexible intestinal zones |

Mini Case Study: Tracking Wombat Behavior Through Scat

In Tasmania, wildlife biologists used fecal pile patterns to monitor wombat populations in fragmented forest habitats. Researchers observed that healthy individuals deposited neatly stacked cubes near burrow entrances and trail intersections. In contrast, stressed or displaced wombats left scattered, unstacked droppings.

By analyzing pile structure—not just presence—the team inferred social stress levels and habitat quality. One site showed frequent overturned piles, indicating high traffic or competition. Conservationists responded by installing buffer zones and artificial mounds to encourage stable marking behavior. Within six months, pile organization improved, suggesting reduced conflict.

This case illustrates how understanding the function of cube-shaped poop extends beyond curiosity—it supports real-world conservation strategies.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can other animals produce cube-shaped poop?

No known mammal besides the wombat produces consistently cube-shaped feces. Some insects and arthropods excrete angular waste due to rapid desiccation, but none achieve the same level of geometric definition through muscular control.

Does the cube shape hurt the wombat during excretion?

No evidence suggests discomfort. The formation occurs gradually over days as the feces dry and are compressed in the lower intestine. The edges are smooth enough not to cause tissue damage, despite their angular appearance.

Are all wombat species’ poop identical?

All three extant species—common wombat, northern hairy-nosed, and southern hairy-nosed—produce similarly shaped droppings. Minor size differences exist based on diet and body mass, but the cuboid geometry remains consistent across species.

Actionable Checklist: Understanding Animal Adaptations Like a Scientist

- Observe unusual physical traits in animals (e.g., shape, color, texture).

- Ask: What environmental challenge might this solve?

- Research anatomical structures linked to the trait.

- Consider behavioral context (feeding, mating, defense, communication).

- Look for interdisciplinary implications (engineering, medicine, design).

Conclusion: Nature’s Ingenious Designs Are Worth Studying

The cube-shaped poop of the wombat is far more than a bizarre footnote in biology. It exemplifies how evolution fine-tunes even the most mundane bodily functions for survival advantage. From variable intestinal elasticity to strategic territorial signaling, every aspect serves a purpose refined over millennia.

Moreover, this phenomenon reminds us that innovation often hides in plain sight—even in what we traditionally consider waste. By studying nature’s solutions with curiosity and rigor, we unlock ideas that can reshape technology, medicine, and conservation.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?