At first glance, the number 1 seems like it should be prime. It’s only divisible by 1 and itself—so what’s the issue? The confusion is common, but the answer lies not in arithmetic alone, but in the deeper structure of mathematics. The exclusion of 1 from the list of prime numbers isn’t arbitrary; it’s essential to preserving consistency across number theory. Understanding why requires revisiting the precise definition of a prime number, exploring historical shifts in mathematical thinking, and recognizing the practical consequences of allowing 1 into the prime club.

The Modern Definition of a Prime Number

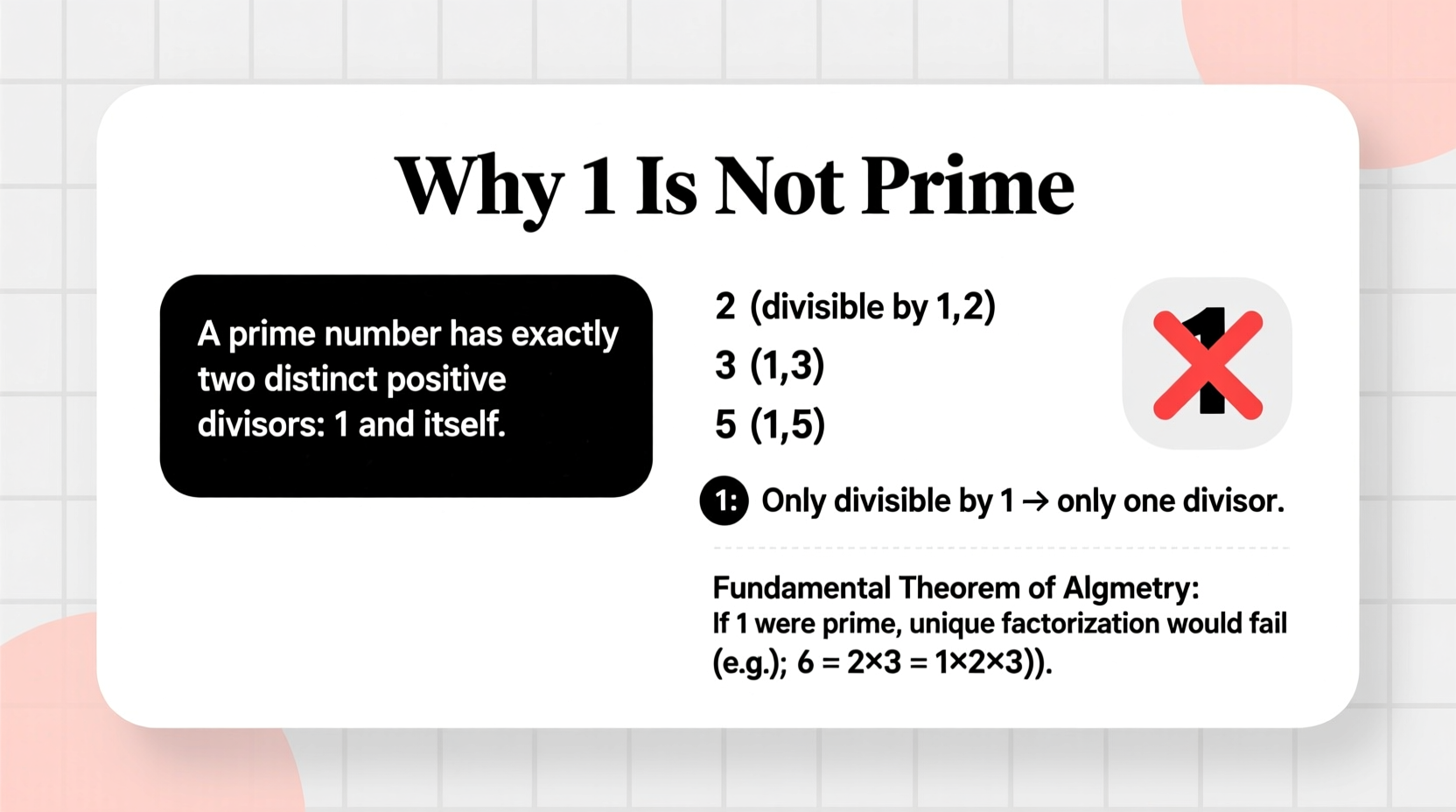

A prime number is defined as a natural number greater than 1 that has exactly two distinct positive divisors: 1 and itself. This seemingly simple condition carries important implications. Let’s break it down:

- Natural number: We’re only considering positive integers (1, 2, 3, ...).

- Greater than 1: This immediately excludes 1 from consideration under the standard definition.

- Exactly two distinct positive divisors: A prime must be divisible by precisely two different numbers.

Now consider the number 1. Its only positive divisor is 1 itself. That means it has just one positive divisor, not two. Therefore, it fails the “exactly two divisors” requirement. While this may appear like a technicality, it's actually a safeguard for deeper mathematical principles.

Historical Context: Was 1 Ever Considered Prime?

Interestingly, 1 was considered a prime number by many mathematicians in earlier centuries. Euclid, in his foundational work *Elements*, did not explicitly exclude 1, though he worked primarily with primes starting from 2. In the 18th and early 19th centuries, some textbooks and scholars listed 1 among the primes.

However, as number theory matured, especially with the development of the Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic, inconsistencies began to arise when 1 was treated as prime. Mathematicians realized that including 1 disrupted unique factorization—the idea that every integer greater than 1 can be expressed uniquely as a product of primes, up to the order of the factors.

“Allowing 1 to be prime would destroy the uniqueness of prime factorizations, which is central to much of modern number theory.” — Dr. Alan Reyes, Number Theorist, University of Chicago

The Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic and Why It Matters

The Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic states that every integer greater than 1 can be written as a unique product of prime numbers, apart from the order of the factors. For example:

- 12 = 2 × 2 × 3

- 30 = 2 × 3 × 5

- 7 = 7 (already prime)

If we allowed 1 to be prime, this uniqueness would collapse. Since multiplying by 1 doesn’t change a number, we could insert any number of 1s into a factorization:

- 12 = 2 × 2 × 3

- 12 = 1 × 2 × 2 × 3

- 12 = 1 × 1 × 2 × 2 × 3

- ...and so on indefinitely.

Suddenly, there are infinitely many ways to write the same number as a product of primes. This violates the core principle of unique factorization. To preserve this critical property, mathematicians formally excluded 1 from the set of primes.

Comparing 1, Primes, and Composites

To clarify the distinction, here’s how 1 compares to prime and composite numbers:

| Type | Definition | Examples | Why 1 Doesn’t Fit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prime | Greater than 1, exactly two distinct positive divisors | 2, 3, 5, 7, 11 | Only has one divisor (itself) |

| Composite | Greater than 1, more than two positive divisors | 4, 6, 8, 9, 10 | Not greater than 1 and doesn’t have multiple divisors |

| Unit | Number with a multiplicative inverse in the integers | 1, -1 | Belongs to a separate category: units |

Notice that 1 belongs to a special class called units—numbers that divide 1. Units are not considered prime or composite because they don’t contribute meaningfully to factorization in the way primes do.

Common Misconceptions and Clarifications

Many people believe that since 1 cannot be divided evenly by any number other than 1, it must be prime. But this overlooks the structural role primes play in mathematics. Being \"hard to divide\" isn’t enough; primes are building blocks. And 1 doesn’t build anything—it’s neutral, like the number 0 in addition.

Another misconception is that the definition was changed just to make things neat. In reality, the exclusion emerged naturally from the need for consistent, powerful theorems. Mathematics evolves not through arbitrary rules, but through necessity driven by logic and application.

Step-by-Step: How to Determine If a Number Is Prime

Here’s a reliable method to test whether a number is prime, keeping in mind why 1 is excluded:

- Check if the number is less than or equal to 1. If yes, it’s not prime.

- List all positive integers less than the number. Test divisibility by each (except 1 and the number itself).

- If any divide evenly (no remainder), the number is composite.

- If none divide evenly, and the number is greater than 1, it’s prime.

Applying this to 1: Step 1 disqualifies it immediately. No further testing is needed.

Mini Case Study: The Classroom Confusion

In a high school math class, students were asked to list all prime numbers less than 10. One student confidently wrote: 1, 2, 3, 5, 7. When the teacher marked 1 incorrect, the student protested: “But 1 is only divisible by 1 and itself!”

The teacher responded by asking the class to factor 6. Everyone agreed: 2 × 3. Then she asked, “What if we allow 1 as prime? Can we write 6 another way?” Hands went up: “1 × 2 × 3,” “1 × 1 × 2 × 3,” even “1⁵ × 2 × 3.”

The realization spread quickly: allowing 1 as prime breaks the idea that factorization is unique. From that moment, the rule made sense—not as memorization, but as protection of a deeper truth.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is 1 a composite number?

No. Composite numbers are defined as natural numbers greater than 1 that have more than two positive divisors. Since 1 does not meet the “greater than 1” condition, it is neither prime nor composite.

Could we redefine primes to include 1?

We could, but doing so would require rewriting countless theorems and definitions to account for non-unique factorizations. The cost outweighs any benefit. Mathematics favors definitions that simplify, not complicate, the framework.

Are there any number systems where 1 is considered prime?

In standard integer arithmetic, no. However, in some abstract algebraic structures, the concept of “prime elements” is more nuanced, and units (like 1) are explicitly excluded for similar reasons—to preserve unique factorization in rings.

Conclusion: Clarity Through Precision

The decision to exclude 1 from the prime numbers is not about stubborn rules or historical accident. It reflects a deep commitment to coherence in mathematics. By requiring primes to be greater than 1 with exactly two divisors, we protect the integrity of factorization, enable powerful theorems, and maintain a clean classification system.

Understanding why 1 isn’t prime teaches a broader lesson: in math, definitions aren’t just labels—they’re tools. Good definitions unlock insight, prevent contradictions, and guide discovery. The next time someone asks why 1 isn’t prime, you won’t just recite a rule—you’ll explain the reasoning behind one of mathematics’ quiet but essential conventions.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?