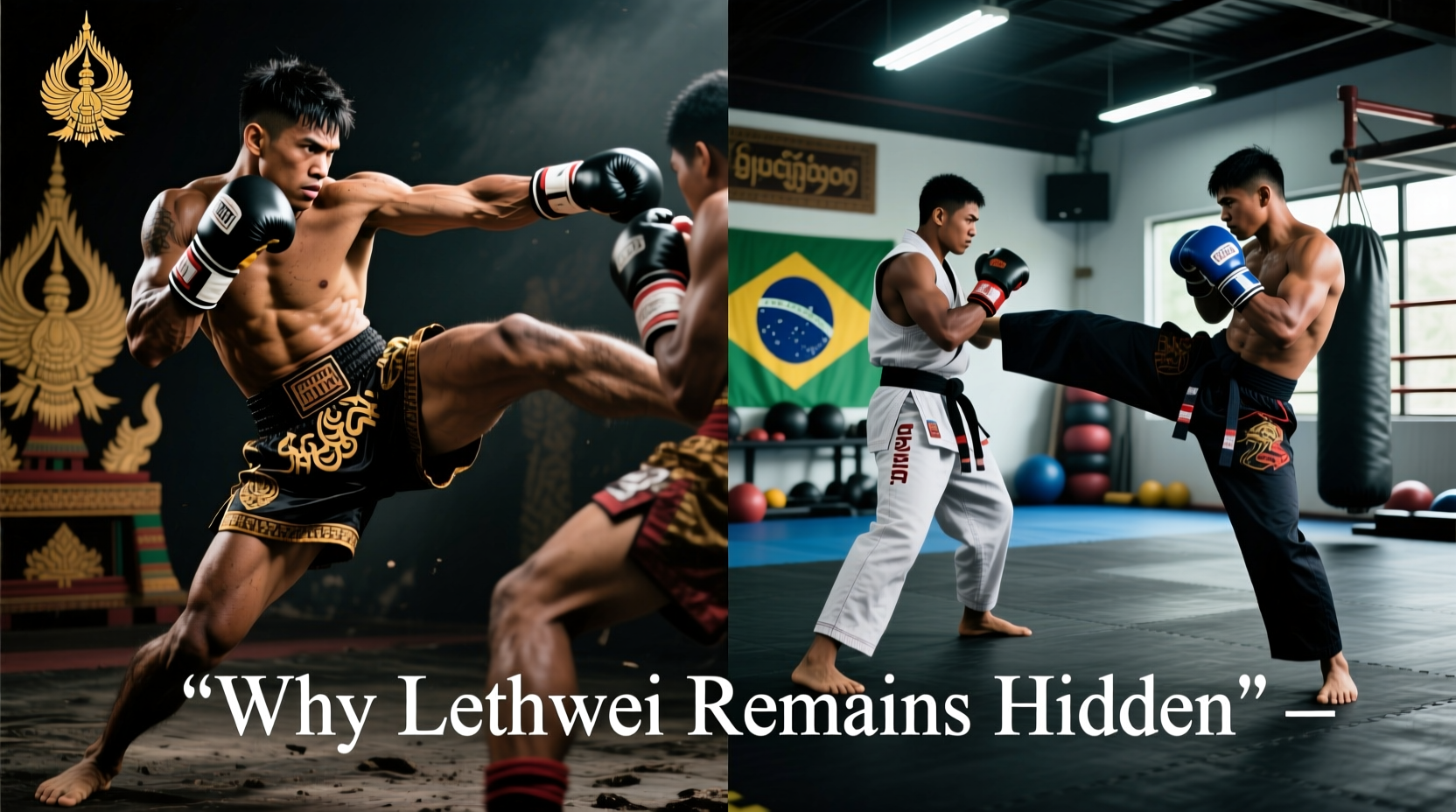

Lethwei, often called “the art of nine limbs,” stands among the most unforgiving combat sports in the world. Unlike Muay Thai, which allows eight points of contact (fists, elbows, knees, feet), Lethwei permits headbutts—making it one of the few full-contact disciplines where such strikes are legal. It originates from Myanmar and has centuries of cultural significance. Yet, despite its intensity, authenticity, and proven effectiveness in real combat, Lethwei remains largely absent from mainstream martial arts schools and global training circuits. The question arises: why isn’t Lethwei taught widely? The answer lies in a complex interplay of cultural, structural, legal, and economic factors that have kept this powerful art form on the fringes of the international martial arts community.

Cultural Isolation and Geographic Limitations

Myanmar’s long history of political isolation has significantly impacted the global spread of Lethwei. For decades, the country was under military rule with strict limitations on foreign access, media coverage, and international exchange. This isolation meant that even as Muay Thai flourished across Thailand and gained popularity in the West through tourism and fight promotions, Lethwei remained confined within national borders.

The sport is deeply embedded in local festivals and village traditions, often showcased during religious or seasonal events. While this preserves its authenticity, it also limits standardization and formal instruction outside rural communities. There is no centralized governing body with the resources or mandate to promote Lethwei internationally in the way organizations like the World Muay Thai Council do for Thai boxing.

Extreme Physical Risk and Safety Concerns

Lethwei is not just aggressive—it is intentionally brutal. Fighters compete bare-knuckled, can use headbutts freely, and fights only end by knockout or stoppage; draws are common because there is no decision system unless a fighter is rendered unconscious. This level of danger raises serious safety concerns, especially in countries with strict liability laws and insurance regulations.

In many Western nations, athletic commissions regulate combat sports heavily. Events must meet medical, equipment, and officiating standards. Bare-knuckle fighting with headbutts fails to meet these criteria almost universally. Even sanctioned bare-knuckle boxing leagues avoid headbutts due to concussion risks. As a result, teaching or promoting Lethwei openly could expose instructors and gyms to legal action or loss of insurance coverage.

“Lethwei is raw, unfiltered combat. That’s its beauty—and its biggest barrier.” — Dave Carter, Combat Sports Historian and Author of *Fighting Nations*

Lack of Standardized Curriculum and Global Infrastructure

Unlike Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, Karate, or even Muay Thai, Lethwei lacks an organized, scalable curriculum suitable for global dissemination. Training in Myanmar is typically apprenticeship-based, passed down informally from master to student, with little emphasis on grading systems, certification, or pedagogical structure.

There are no internationally recognized Lethwei associations offering instructor accreditation, standardized techniques, or progressive belt ranks. Without such infrastructure, martial arts schools hesitate to adopt Lethwei as a formal program. Gym owners need structured curricula, marketing materials, and clear progression paths to attract students and justify tuition fees.

| Martial Art | Global Associations | Standardized Ranking | Regulated International Events |

|---|---|---|---|

| Muay Thai | Yes (WMC, IFMA) | Yes (Pra Jiad & Rajadamnern belts) | Frequent (World Championships, Grand Prix) |

| Lethwei | Limited (Myanmar Lethwei Federation) | No consistent system | Rare, mostly domestic |

| Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu | IBJJF, ADCC | Yes (Colored belts) | Global tournaments annually |

Economic and Market Viability Challenges

For any martial art to spread globally, it must be economically sustainable. Instructors need to earn a living, and schools must generate revenue. Lethwei struggles here for several reasons:

- Low commercial appeal: The brutality deters casual learners and parents seeking safe activities for children.

- Limited sponsorship: Few brands want to associate with a sport perceived as excessively violent.

- No major media presence: Unlike UFC or ONE Championship, which feature Muay Thai fighters regularly, Lethwei has minimal broadcast deals or streaming visibility.

- Training cost vs. return: High injury rates increase medical costs and reduce long-term practitioner retention.

Compare this to the rise of MMA, which blended multiple disciplines into a marketable, regulated spectacle. Lethwei, by contrast, resists modification for entertainment value. Purists argue that softening the rules would destroy its essence—yet without adaptation, growth remains stunted.

Case Study: Attempted Global Expansion in Japan

In 2016, Japanese promoter Akio Kimura launched the \"Lethwei in Japan\" series, aiming to introduce the sport to a new audience. He brought top Burmese fighters to Tokyo, modified rules slightly for safety (allowing judges’ decisions), and aired events on regional networks. Initially, interest surged among hardcore fight fans.

However, after two years, the promotion folded. Reasons included low ticket sales, difficulty securing venue insurance, and resistance from Japanese martial artists who viewed headbutts as unsportsmanlike. One trainer noted, “Our students loved the power and realism, but parents pulled their kids out after seeing footage of head wounds.” The case illustrates how cultural values and risk tolerance shape acceptance—even in a country with deep martial traditions.

What Would It Take to Widen Access?

Expanding Lethwei’s reach doesn’t require abandoning its roots—but it does demand strategic compromise. Here’s what could help bridge the gap:

- Create hybrid training programs: Teach Lethwei techniques in controlled environments, focusing on conditioning, clinch work, and footwork without live headbutt sparring.

- Establish international federations: Develop a global body to standardize rules, certify coaches, and organize amateur competitions.

- Promote via digital platforms: Use YouTube, podcasts, and online courses to share technique breakdowns and historical context.

- Partner with existing gyms: Offer Lethwei as a specialty module within Muay Thai or MMA schools.

- Introduce protective gear: Experiment with padded headguards and modified rules for amateur levels to reduce injury risk.

FAQ

Is Lethwei more dangerous than Muay Thai?

Yes, significantly. The combination of bare-knuckle striking, legal headbutts, and no point-based scoring increases the risk of severe injury, including concussions and facial fractures. Medical oversight is often minimal in traditional matches.

Can I learn Lethwei outside Myanmar?

Opportunities are limited but growing. A few specialized gyms in the UK, Germany, and the US offer Lethwei classes, often led by diaspora fighters or enthusiasts who trained in Myanmar. Online seminars and video tutorials are also emerging.

Why don’t UFC or ONE Championship include Lethwei fighters?

While some Lethwei practitioners transition to MMA, the pure form of Lethwei isn’t compatible with modern cage fighting rules. Headbutts are illegal in all major promotions, and bare-knuckle rounds aren’t permitted. However, Lethwei-trained athletes bring valuable toughness and clinch skills to the octagon.

Conclusion

Lethwei isn’t taught widely because it exists at the intersection of tradition, danger, and logistical challenge. Its cultural roots run deep, but its path to global adoption is blocked by safety regulations, lack of infrastructure, and economic hurdles. Yet, its raw effectiveness and unique identity make it too compelling to ignore forever. With careful adaptation—preserving its spirit while making it accessible—Lethwei could find a place alongside other respected martial arts. For now, it remains a hidden gem, known to few but unforgettable to those who experience it.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?