Lipids are essential biomolecules that play critical roles in energy storage, cell membrane formation, and signaling. Despite being fundamental to life, lipids stand apart from other major biological molecules like proteins, nucleic acids, and carbohydrates—particularly in one key way: they are not classified as polymers. This distinction often puzzles students and science enthusiasts alike. To understand why, it’s necessary to examine the definition of a polymer, the structural characteristics of lipids, and how these features determine their classification in biochemistry.

What Defines a Polymer?

A polymer is a large molecule composed of repeating subunits called monomers, linked together through covalent bonds in a process known as polymerization. The prefix \"poly-\" means \"many,\" and \"-mer\" refers to \"parts\" or \"units.\" Common examples include proteins (made of amino acid monomers), DNA (built from nucleotide monomers), and starch (a chain of glucose units).

The hallmark of a true polymer is its repetitive, linear structure formed via condensation reactions, where each monomer joins the growing chain with the release of a water molecule. These macromolecules exhibit high molecular weight and often have predictable patterns in their backbone structure.

“Polymers are defined by both composition and architecture—their repeating units and the regularity of their linkage.” — Dr. Alan Reyes, Biochemist, University of California, Berkeley

Basic Structure of Lipids

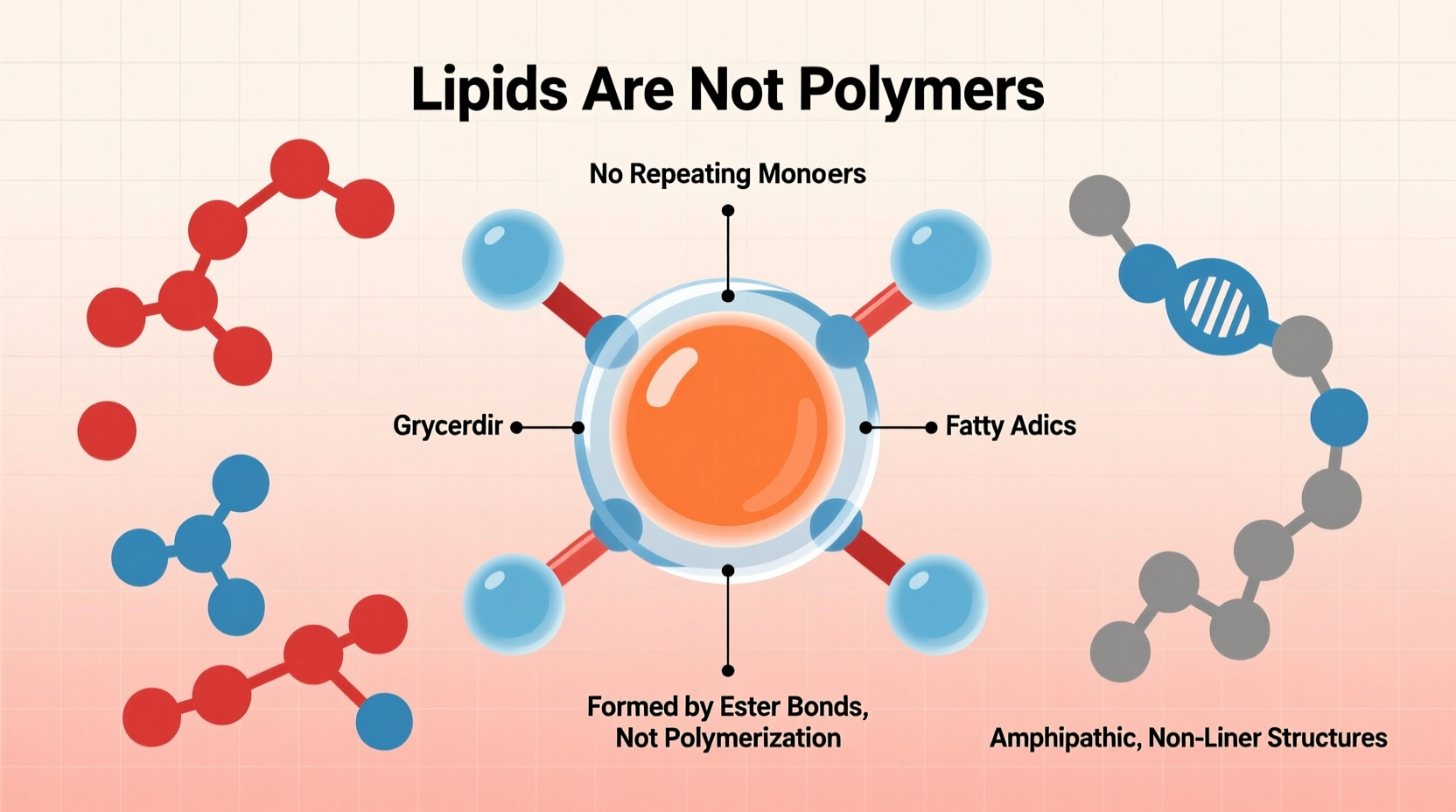

Lipids are a diverse group of hydrophobic or amphiphilic molecules that include fats, oils, waxes, phospholipids, and steroids. Unlike polymers, lipids do not share a single unifying structural framework. However, many common lipids—such as triglycerides—are built from glycerol and fatty acids.

In a triglyceride, three fatty acid chains attach to a glycerol backbone via ester linkages. While this may resemble a polymer at first glance, the lack of repetition and chain elongation disqualifies it from polymer status. Each fatty acid can vary significantly in length and saturation, resulting in a structurally heterogeneous molecule rather than a sequence of identical repeating units.

Fatty Acids and Glycerol: Building Blocks, Not Monomers

Although glycerol and fatty acids serve as precursors in lipid synthesis, they are not monomers in the biochemical sense. Monomers polymerize into long, directional chains (e.g., amino acids forming polypeptides). In contrast, fatty acids bind individually to glycerol in a limited, fixed arrangement—typically one glycerol molecule binds up to three fatty acids. There is no propagation of a chain beyond this point.

Moreover, different types of lipids use entirely different building blocks. For example, steroids like cholesterol are derived from fused carbon rings (based on the cyclopentanoperhydrophenanthrene skeleton), bearing no resemblance to fatty acids or glycerol. Sphingolipids use sphingosine instead of glycerol. This chemical diversity further underscores why lipids cannot be grouped under a single polymeric model.

Key Differences Between Lipids and Polymers

| Feature | Polymers (e.g., Proteins, DNA) | Lipids (e.g., Triglycerides, Phospholipids) |

|---|---|---|

| Monomeric Units | Identical or similar repeating units (amino acids, nucleotides) | No consistent repeating unit; varied components |

| Bond Formation | Repetitive covalent linkages (peptide, phosphodiester bonds) | Limited ester or amide bonds; no chain extension |

| Molecular Shape | Long, linear chains (often folded) | Branched, globular, or bilayer-forming structures |

| Synthesis Mechanism | Polymerization (dehydration synthesis over multiple steps) | Stepwise assembly without propagation |

| Classification Basis | Structure and monomer type | Solubility (hydrophobic nature) |

This comparison highlights a central truth: lipids are classified not by structural homology but by physical behavior—specifically, their insolubility in water and solubility in nonpolar solvents. This functional definition sets them apart from polymers, which are categorized based on molecular architecture.

Why Does It Matter That Lipids Aren’t Polymers?

Understanding this distinction has practical implications in biology and medicine. For instance, when studying metabolic pathways, recognizing that lipids are assembled differently than proteins explains why enzymes like lipases break down ester bonds in fats, while proteases target peptide bonds in polypeptides.

In nutrition, knowing that triglycerides consist of discrete units helps explain caloric density—each gram provides about 9 kcal, more than double that of carbohydrates or proteins. This energy richness stems from the high number of C-H bonds in fatty acid chains, not from polymeric structure.

Additionally, in cellular biology, the non-polymeric nature of phospholipids enables them to form fluid bilayers. Their two fatty acid tails and polar head group allow spontaneous self-assembly into membranes—something rigid, linear polymers could not achieve.

Mini Case Study: Cell Membrane Formation

Consider the human red blood cell. Its flexible, semi-permeable membrane relies on phospholipids arranging themselves into a bilayer. If phospholipids were rigid polymers, they couldn’t maintain the dynamic fluidity required for cell deformation as the cell passes through narrow capillaries. Instead, the individual, non-repeating nature of each phospholipid allows rotational and lateral movement within the membrane plane, enabling resilience and adaptability.

This real-world function illustrates how the absence of polymeric constraints actually enhances biological utility in certain contexts.

Common Misconceptions About Lipids and Polymers

- Misconception 1: “Since lipids can be large, they must be polymers.” Reality: Size alone doesn’t define a polymer. Many small molecules are larger than some polymers, but only those with repeating monomeric units qualify.

- Misconception 2: “Fatty acids are monomers because they link to glycerol.” Reality: A monomer must be capable of joining a growing chain. Fatty acids attach once and stop—no chain propagation occurs.

- Misconception 3: “All biological macromolecules are polymers.” Reality: Lipids are macromolecules due to size and importance, but not all macromolecules are polymers. Lipids are a key exception.

Checklist: How to Identify a True Biological Polymer

- Ask: Is there a repeating unit? (e.g., glucose in starch)

- Determine: Are multiple identical or similar subunits linked together?

- Check: Does the molecule grow via sequential addition of monomers?

- Analyze: Is the backbone chemically uniform (e.g., sugar-phosphate in DNA)?

- Verify: Is it synthesized through polymerization (dehydration synthesis over many cycles)?

If most answers are \"yes,\" you’re likely dealing with a polymer. If not, as with lipids, another classification applies.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are any lipids made of repeating units?

No known natural lipids consist of repeating monomeric units in a chain-like fashion. Even complex lipids like glycolipids combine sugars, fatty acids, and alcohols in limited, non-repetitive arrangements. There is no biological equivalent to a \"lipid chain\" analogous to a polypeptide.

Can synthetic lipids be designed as polymers?

In laboratory settings, researchers have created synthetic lipid-like polymers for drug delivery systems. However, these are engineered materials and not found in nature. Biologically, lipids remain non-polymeric.

Why are lipids grouped with macromolecules if they’re not polymers?

Lipids are often included among macromolecules due to their large size and vital cellular functions, even though they don’t meet the strict structural criteria for polymers. Classification in biology sometimes blends function with chemistry, leading to exceptions like this.

Conclusion: Embracing Molecular Diversity in Biology

The fact that lipids are not polymers reveals an important principle in biochemistry: not all essential molecules follow the same structural rules. While proteins, nucleic acids, and polysaccharides rely on repetition and linearity, lipids exploit variety and modularity. Their strength lies in versatility—not uniformity.

Recognizing this distinction deepens our understanding of how life builds complexity using different strategies. From energy storage to membrane dynamics, lipids perform indispensable roles precisely because they break the mold of traditional polymer design.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?