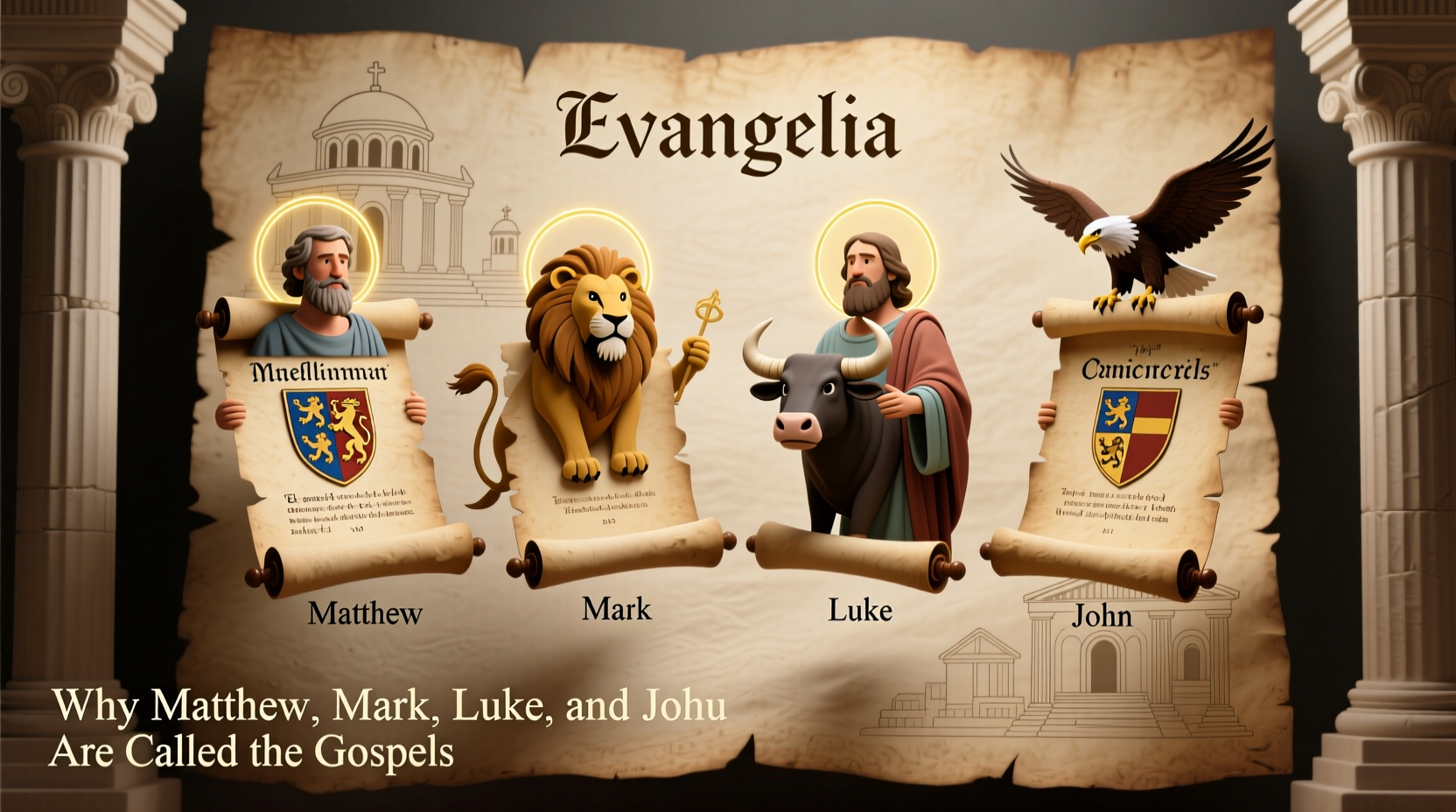

The four New Testament books of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John are universally known as the \"Gospels.\" This designation is more than a label—it carries deep theological, historical, and linguistic meaning. These writings form the foundation of Christian belief, chronicling the life, teachings, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ. But why exactly are they called \"gospels\"? Understanding this term unlocks insight into early Christianity’s worldview, mission, and message.

The word \"gospel\" appears frequently in modern religious discourse, yet its origins and implications are often overlooked. To appreciate why these four texts hold such a title—and why no others in Scripture do—we must explore the etymology of the word, the purpose behind these accounts, and the early church’s criteria for inclusion.

The Meaning of “Gospel”

The English word \"gospel\" comes from the Old English *godspel*, meaning \"good news\" or \"glad tidings.\" This translation reflects the Greek term euangelion (εὐαγγέλιον), which literally means \"good message\" or \"good announcement.\" In the ancient world, euangelion was used to describe royal proclamations—such as the birth of a king or a military victory—that brought joyous news to the public.

In the context of the New Testament, the \"gospel\" refers specifically to the transformative message of salvation through Jesus Christ. The writers of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John weren’t merely recording history; they were proclaiming a divine intervention in human affairs—the arrival of the Messiah, the fulfillment of prophecy, and the inauguration of God’s Kingdom on earth.

“Paul, a servant of Christ Jesus, called to be an apostle, set apart for the gospel of God.” — Romans 1:1

This verse illustrates how early Christians viewed the gospel not just as a book, but as a living message rooted in God’s redemptive plan. The four canonical Gospels are named as such because each one presents this good news in narrative form, centered on the person and work of Jesus.

Why Only Four? Historical and Theological Criteria

While dozens of early Christian writings claimed to record Jesus’ life—including the Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel of Peter, and others—only Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John were accepted into the biblical canon. Their recognition as authoritative \"Gospels\" was based on several key factors:

- Apostolic connection: Each Gospel is either written by an eyewitness (Matthew, John) or closely associated with one (Mark with Peter, Luke with Paul).

- Widespread acceptance: These texts were read in churches across the Roman Empire by the late second century.

- Doctrinal consistency: They align with the teachings of the broader New Testament and early Christian orthodoxy.

- Historical reliability: Early church leaders like Irenaeus and Tertullian defended them as trustworthy accounts.

Irenaeus of Lyons, writing around 180 AD, explicitly argued that there must be exactly four Gospels, comparing them to the four corners of the earth and the four winds—symbolizing completeness and universality.

Different Perspectives, One Message

Though united in proclaiming the good news of Jesus, each Gospel offers a distinct perspective. Recognizing these differences enhances understanding of why all four are necessary and how they complement one another.

| Gospel | Author | Primary Audience | Key Emphasis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Matthew | Matthew, former tax collector | Jewish readers | Jesus as the promised Messiah and fulfillment of Old Testament prophecy |

| Mark | John Mark, companion of Peter and Paul | Roman/Gentile readers | Jesus as the suffering servant and powerful miracle-worker |

| Luke | Luke, physician and historian | Greek-speaking Gentiles | Jesus as the compassionate Savior of all people, especially the marginalized |

| John | John, son of Zebedee and disciple of Jesus | Broad Christian audience | Jesus as the divine Son of God, eternal Word made flesh |

This table highlights how each Gospel writer tailored his account to communicate the same core truth—the identity and mission of Jesus—in culturally relevant ways. Together, they form a multifaceted portrait of Christ that no single narrative could capture alone.

A Closer Look at John’s Theological Depth

While the first three Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke) are often grouped as the \"Synoptic Gospels\" due to their similar structure and content, John stands apart in style and emphasis. It opens not with a birth narrative but with a profound theological declaration: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God” (John 1:1).

John’s Gospel is less concerned with chronological detail and more focused on revealing Jesus’ divine nature. His use of symbolic miracles (\"signs\"), extended discourses, and personal encounters (like with Nicodemus and the Samaritan woman) invites readers into a deeper spiritual understanding. This reinforces why it, too, is rightly called a \"gospel\"—it proclaims the ultimate good news: God has come near in human form.

How the Gospels Functioned in Early Christianity

In the first-century church, the Gospels were not simply devotional literature—they were tools for teaching, worship, and evangelism. Early Christians gathered to hear these narratives read aloud, often alongside letters from apostles like Paul. The proclamation of the \"gospel\" was central to baptism, instruction, and missionary outreach.

For example, when Philip encountered the Ethiopian eunuch in Acts 8, he didn’t begin with abstract theology. He started with Isaiah and explained “the good news about Jesus” (Acts 8:35). This reflects how the Gospel narratives served as the backbone of Christian preaching.

“The Gospel is not a theory about God—it is the story of what God has done.” — N.T. Wright, New Testament Scholar

This quote captures the essence of why Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John are called Gospels: they are not philosophical treatises, but historical narratives infused with divine significance. They invite readers not just to believe ideas, but to enter a story—the story of redemption.

Common Misconceptions About the Gospels

Several misunderstandings persist about these four books:

- Misconception: The Gospels were written decades after Jesus’ death, so they’re unreliable.

Reality: While written between 70–100 AD, they stem from strong oral traditions preserved within living memory and under the oversight of apostles. - Misconception: They contradict each other.

Reality: Differences in detail reflect varied perspectives, not errors—much like multiple eyewitnesses describing the same event. - Misconception: Other \"gospels\" were suppressed for political reasons.

Reality: Most non-canonical gospels were rejected because they lacked apostolic authority, appeared much later, or taught unorthodox views (e.g., Gnostic dualism).

Checklist: How to Read the Gospels Effectively

To fully grasp why these books are called Gospels, apply the following practices:

- Read them chronologically to see Jesus’ ministry unfold.

- Compare parallel passages across Matthew, Mark, and Luke to appreciate different emphases.

- Observe recurring themes: the Kingdom of God, forgiveness, faith, and discipleship.

- Pay attention to how each author portrays Jesus’ identity.

- Reflect on how the \"good news\" applies to your life today.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why aren’t other books about Jesus called Gospels?

Many texts claiming to be \"gospels\" emerged in the second century and later, but they lacked apostolic authority, were written long after the events, and often contained mystical or heretical teachings. The early church carefully evaluated writings based on authenticity, consistency, and widespread use—criteria only Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John met.

Do the Gospels present the same Jesus?

Yes. While each emphasizes different aspects—Matthew highlights His kingship, Mark His action, Luke His compassion, and John His divinity—they all affirm His identity as the Son of God, teacher, healer, and sacrificial Savior. The variations enrich rather than contradict the portrait.

Can the Gospels be trusted as historical documents?

Yes. Ancient historians like Tacitus and Josephus indirectly confirm details about Jesus’ existence, crucifixion under Pilate, and the rise of His followers. Moreover, the Gospels reflect first-century Palestinian geography, culture, and customs with remarkable accuracy, supporting their reliability.

Conclusion: The Enduring Power of the Good News

The reason Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John are called Gospels lies not in tradition alone, but in their purpose: to proclaim the most important message in human history. They are not biographies in the modern sense, nor theological essays—but sacred announcements of salvation. Each one invites readers to encounter Jesus, respond in faith, and become part of the ongoing story of redemption.

These four books have shaped civilizations, inspired movements, and transformed countless lives. Calling them \"Gospels\" reminds us that Christianity is fundamentally a message of hope—a declaration that love has triumphed over sin, and life has conquered death.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?