HIV, or human immunodeficiency virus, remains one of the most studied viruses in medical history. Despite decades of research and public awareness campaigns, misconceptions persist—especially around how HIV spreads. One common myth is that mosquitoes could transmit HIV through bites, much like they do with malaria or dengue. But this is not true. The reality is that mosquitoes are biologically incapable of transmitting HIV to humans. Understanding why requires a closer look at both mosquito biology and the nature of the HIV virus itself.

The fear stems from a logical question: if mosquitoes can carry diseases like Zika or West Nile virus, why not HIV? The answer lies in the fundamental differences between how various pathogens interact with insect vectors. Unlike those viruses, HIV cannot survive or replicate inside a mosquito, nor can it be passed on during feeding. This article breaks down the science behind this crucial distinction, offering clarity and reassurance based on virology, entomology, and epidemiological evidence.

How Mosquitoes Transmit Diseases

To understand why HIV isn’t transmitted by mosquitoes, it’s essential to first grasp how mosquitoes *do* spread other diseases. When a female mosquito bites a human, she draws blood to nourish her eggs. During this process, she injects saliva into the skin to prevent clotting, which allows her to feed more efficiently. In some cases, disease-causing pathogens present in an infected host’s blood can enter the mosquito’s body.

For transmission to occur, two conditions must be met:

- The pathogen must survive and often multiply inside the mosquito.

- The pathogen must migrate to the mosquito’s salivary glands so it can be injected into the next host during a bite.

Viruses like dengue, chikungunya, and Zika meet these criteria. They infect mosquito cells, replicate, and reach the salivary glands within days. Malaria parasites also undergo complex life cycles inside the insect. However, HIV fails at every stage of this process.

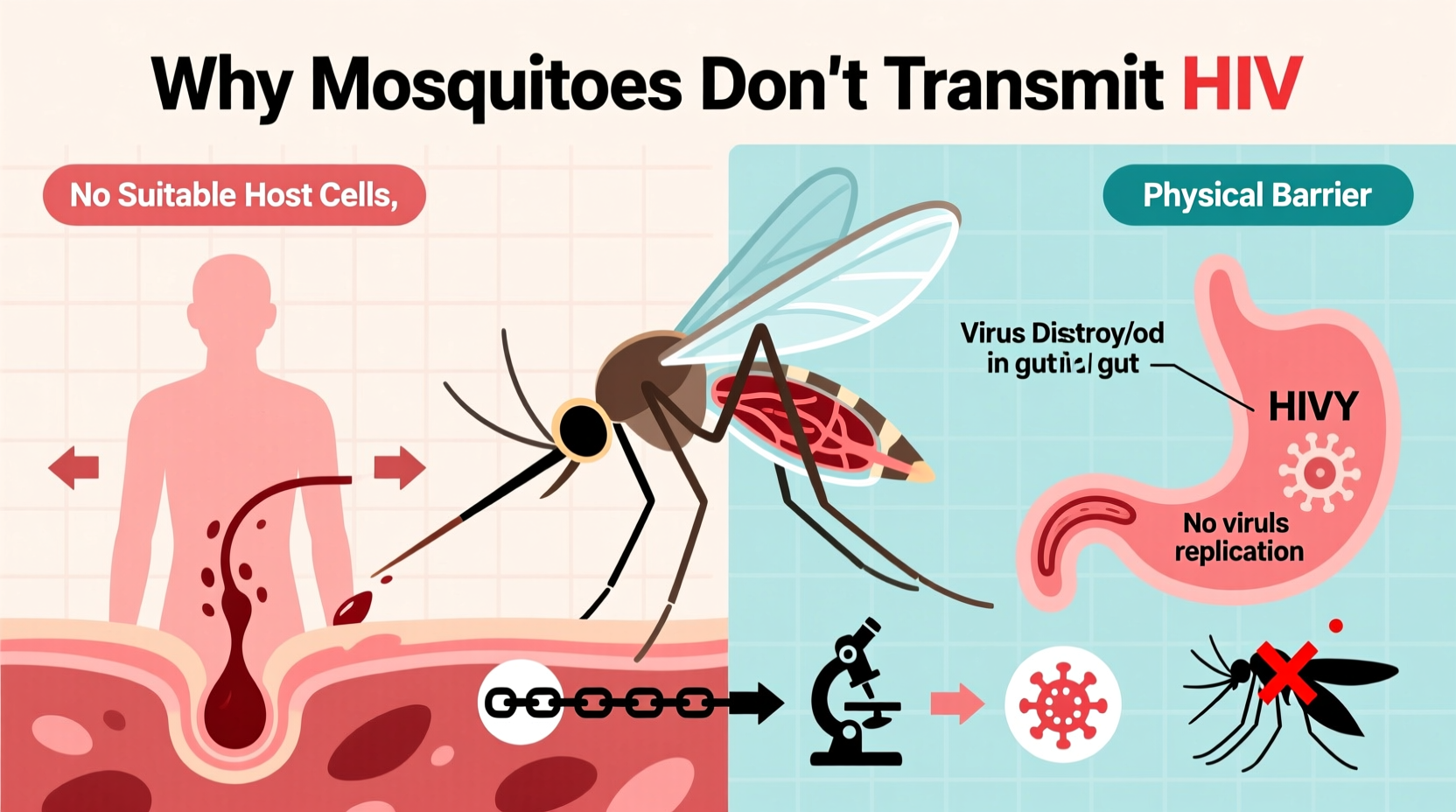

Why HIV Cannot Survive in Mosquitoes

HIV is a fragile virus highly adapted to human biology. Once outside the human bloodstream, it degrades rapidly. Inside a mosquito, several factors prevent HIV from surviving long enough to pose any threat:

- Digestive destruction: When a mosquito ingests HIV-infected blood, the virus enters its digestive tract. There, powerful enzymes break down the blood meal—and the virus along with it. HIV cannot withstand this environment.

- No replication: Unlike arboviruses (arthropod-borne viruses), HIV cannot replicate in insect cells. It requires specific human immune cells (like CD4+ T cells) to reproduce. Mosquitoes lack these entirely.

- No migration to salivary glands: Even if traces of the virus survived digestion, there is no mechanism for HIV to travel from the gut to the salivary glands. Without this step, transmission is impossible.

Studies have confirmed this repeatedly. In controlled laboratory experiments, mosquitoes fed HIV-laden blood showed no detectable virus in their saliva after 24 hours. The virus simply does not persist.

“HIV is exquisitely adapted to humans. It doesn’t infect insects, can’t replicate in them, and is destroyed quickly in their gut.” — Dr. Anthony Fauci, former Director, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Transmission Mechanics: Why Mosquito Bites Don’t Work Like Needles

A frequent source of confusion is the assumption that a mosquito bite works like a dirty hypodermic needle—drawing infected blood from one person and injecting it into another. This analogy is fundamentally flawed.

Unlike a syringe, a mosquito does not have a dual-channel system. Its mouthparts consist of separate tubes: one for drawing blood and another for injecting saliva. There is no backflow of blood from the mosquito’s stomach into the next victim. The tiny amount of blood remaining in the proboscis after feeding is negligible—far below the threshold needed to transmit HIV.

To put this in perspective, studies estimate that even if a mosquito contained HIV particles (which it doesn’t), it would need to regurgitate at least 10 million times its normal saliva volume to deliver an infectious dose. This is physically impossible.

| Factor | HIV Transmission Risk via Mosquito | Actual Disease Example (e.g., Dengue) |

|---|---|---|

| Survival in mosquito | No – destroyed in gut | Yes – replicates in tissues |

| Movement to salivary glands | No | Yes – active migration |

| Injected into new host | No – only saliva is injected | Yes – virus in saliva |

| Epidemiological evidence | Zero documented cases | Millions of cases annually |

Real-World Evidence: No Cases of Mosquito-Borne HIV

If mosquitoes could transmit HIV, we would expect to see patterns similar to other vector-borne diseases—clusters in tropical regions, outbreaks following rainy seasons, or infections in populations with high mosquito exposure but low sexual or needle-related risk factors. Yet, no such pattern exists.

Consider sub-Saharan Africa, where both HIV prevalence and mosquito density are extremely high. Despite millions of people living in close proximity to countless mosquito bites each year, HIV transmission tracks almost exclusively with sexual contact, mother-to-child transmission, or shared needles—not geography or insect exposure.

Similarly, in the United States during the early years of the AIDS epidemic, cases were concentrated among specific demographics—gay men, intravenous drug users, hemophiliacs—while children, outdoor workers, and others with high mosquito exposure remained unaffected unless they fell into a known risk category.

Mini Case Study: The Florida Misconception

In the late 1980s, a small community in southern Florida reported a spike in HIV cases among migrant farmworkers. Local rumors suggested mosquitoes were spreading the virus due to poor living conditions and constant insect bites. Public health officials launched an investigation. After extensive testing and contact tracing, every case was linked to unprotected sex or needle sharing. Not a single case was unexplained or correlated with mosquito exposure. The outbreak underscored how misinformation can spread faster than the virus itself.

Common Myths vs. Scientific Facts

Despite overwhelming evidence, myths about HIV transmission persist. Here’s a quick checklist to clarify what does—and doesn’t—spread HIV:

- ❌ Mosquito bites – No risk

- ❌ Casual contact (shaking hands, hugging) – No risk

- ❌ Sharing food, toilets, or swimming pools – No risk

- ✅ Unprotected sex – High risk

- ✅ Sharing needles or syringes – High risk

- ✅ Mother-to-child (during birth or breastfeeding) – Risk without treatment

Frequently Asked Questions

Can any insect transmit HIV?

No. No insect or arthropod—including ticks, bed bugs, or fleas—can transmit HIV. The virus cannot survive in non-human hosts or vectors. Transmission requires direct entry of infected bodily fluids into the bloodstream or mucous membranes.

If I get bitten by a mosquito right after it bit someone with HIV, can I get infected?

No. As explained, mosquitoes do not transfer blood between people. The feeding mechanism prevents backflow, and any HIV in the ingested blood is destroyed in the mosquito’s gut. There is no risk, even under this scenario.

Why do people still believe mosquitoes can spread HIV?

Misinformation, fear, and misunderstanding of how diseases spread contribute to this myth. Because mosquitoes transmit serious illnesses like malaria and Zika, it’s easy to assume they could carry any bloodborne virus. Education and clear communication from health authorities are key to dispelling such fears.

Conclusion: Trust Science, Not Speculation

The idea that mosquitoes might spread HIV is understandable but entirely unsupported by science. From viral biology to insect physiology, every factor confirms that this mode of transmission is impossible. HIV requires very specific conditions to move from person to person—conditions that mosquito bites simply cannot provide.

Understanding this helps reduce stigma and fear surrounding HIV. It also allows public health resources to focus where they’re truly needed: promoting safe sex, expanding access to clean needles, supporting prenatal care, and ensuring widespread testing and treatment.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?