In their groundbreaking 2012 book *Why Nations Fail*, economists Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson challenge conventional wisdom about global inequality. They argue that the wealth or poverty of nations is not determined by geography, culture, or ignorance—but by political and economic institutions. The central thesis is both powerful and accessible: countries succeed when they develop inclusive institutions, and fail when they are trapped in extractive ones.

This distinction forms the backbone of their analysis, which spans centuries and continents—from the Roman Empire to modern-day North Korea, from the Industrial Revolution in England to the stagnation in sub-Saharan Africa. What emerges is a compelling narrative about power, opportunity, and the human capacity for innovation when systems allow it.

The Core Argument: Inclusive vs. Extractive Institutions

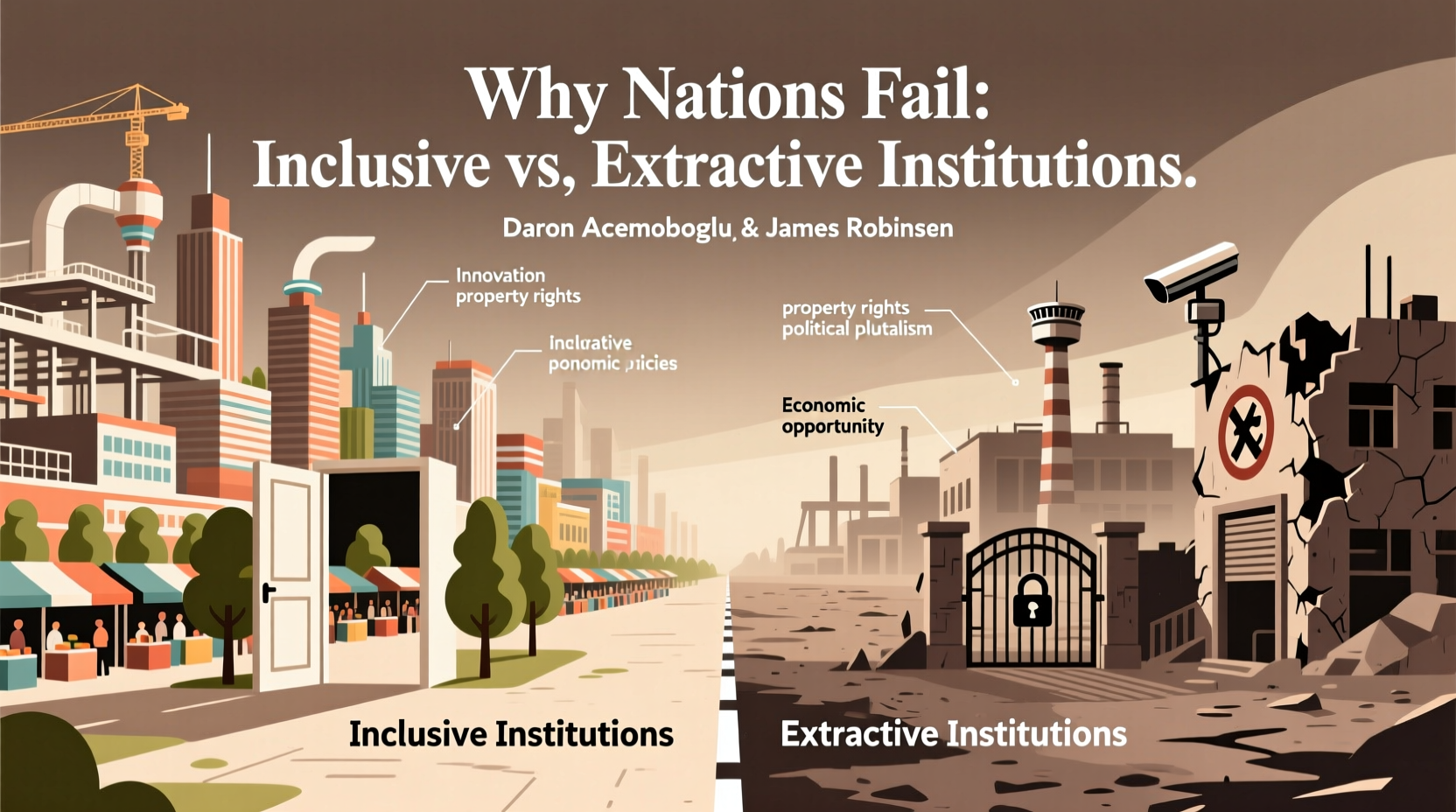

At the heart of *Why Nations Fail* lies a simple but profound dichotomy: inclusive institutions versus extractive institutions.

- Inclusive economic institutions create property rights, encourage investment, reward innovation, and allow broad participation in economic activity.

- Inclusive political institutions distribute power broadly, enforce checks and balances, and enable pluralism and accountability.

- Extractive economic institutions concentrate wealth and resources in the hands of a few, often through coercion or monopolies.

- Extractive political institutions centralize power, suppress dissent, and prevent meaningful participation in governance.

When both political and economic institutions are inclusive, virtuous cycles emerge: citizens innovate, economies grow, and governments become more responsive. When both are extractive, vicious cycles dominate: elites enrich themselves at the expense of society, innovation is stifled, and long-term decline sets in.

“Powerful elites often resist change because it threatens their control—even if that change would make the entire nation richer.” — Daron Acemoglu & James A. Robinson, *Why Nations Fail*

Historical Turning Points and Critical Junctures

Acemoglu and Robinson emphasize that institutional trajectories are not fixed. History is shaped by “critical junctures”—moments when small differences lead to vastly divergent outcomes.

One of the most striking examples is the divergence between Nogales, Arizona (USA), and Nogales, Sonora (Mexico). Identical geography, culture, and population—yet dramatically different standards of living due to differing institutions on either side of the border.

Another pivotal case is the Glorious Revolution of 1688 in England. This event shifted power from the monarchy to Parliament, laying the foundation for secure property rights, financial innovation, and eventually the Industrial Revolution. Compare this to the Ottoman Empire or absolutist France, where monarchs retained unchecked power, suppressing economic dynamism.

Case Study: South Korea vs. North Korea

No comparison illustrates the book’s thesis more starkly than the Korean Peninsula. After World War II, both North and South Korea were poor, war-torn, and under foreign influence. Yet within decades, South Korea became a thriving democracy and technological powerhouse, while North Korea descended into famine, repression, and isolation.

The reason? Institutions.

- South Korea gradually developed inclusive institutions—competitive politics, rule of law, open markets—despite early authoritarian rule.

- North Korea entrenched one of the most extractive systems in history: the Kim dynasty monopolizes power, controls all economic output, and suppresses any form of dissent.

The result is one of the largest income gaps between two ethnically and culturally identical populations. Per capita income in South Korea is over ten times higher than in North Korea—a testament to how institutions shape destiny.

Why Good Policies Aren’t Enough

A common misconception is that poor countries fail because leaders don’t know what policies work. Acemoglu and Robinson reject this technocratic view. They argue that even well-informed leaders may choose bad policies if those policies preserve their power.

For example, colonial powers deliberately established extractive institutions in Africa and Latin America—not out of ignorance, but to exploit resources and labor. These structures persisted after independence because new elites found them useful for maintaining control.

The authors also dismiss the “geography hypothesis” (e.g., tropical climates hinder development) and the “culture hypothesis” (e.g., certain religions discourage growth). If geography were decisive, why do some tropical nations like Singapore thrive? If culture were the key, how could China rapidly industrialize after decades of stagnation?

| Hypothesis | Claim | Counterexample from the Book |

|---|---|---|

| Geography | Poor countries are poor due to climate or disease | Singapore thrives despite tropical location |

| Culture | Values or religion limit economic behavior | South Korea and Ghana share similar cultural roots but vastly different outcomes |

| Ignorance | Leaders simply don’t know the right policies | Many African leaders studied abroad but maintain extractive systems |

Breaking the Cycle: Can Extractive Systems Change?

Change is possible—but difficult. Extractive regimes resist reform because it threatens elite interests. Real transformation usually requires broad-based coalitions that can challenge existing power structures.

The book highlights the role of civil society, worker movements, and political revolutions in pushing societies toward inclusivity. However, not all revolutions lead to better institutions. The Russian Revolution of 1917 replaced one elite with another, creating a new form of extraction under communist rule.

Successful transitions often involve what the authors call “institutional drift”—small, incremental changes that accumulate over time. The Magna Carta, for instance, didn’t instantly democratize England, but it began a process of limiting monarchical power that culminated centuries later in representative government.

Actionable Checklist for Understanding National Development

- Evaluate whether political power is concentrated or distributed.

- Assess whether economic opportunities are available to the majority or reserved for elites.

- Look for historical turning points that shaped current institutions.

- Determine if the legal system protects property rights and enforces contracts impartially.

- Examine whether innovation and entrepreneurship are rewarded or suppressed.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a country with rich natural resources avoid the \"resource curse\"?

Yes—but only if it has strong inclusive institutions. Norway, for example, uses oil wealth transparently through sovereign wealth funds accountable to the public. In contrast, Nigeria and Venezuela have suffered corruption and instability despite vast resources, due to extractive governance.

Is foreign aid effective in helping poor nations develop?

Not in the long run, according to the authors. Aid may provide temporary relief but cannot fix broken institutions. If power remains concentrated in the hands of extractive elites, aid money will likely be misused or diverted. Sustainable development requires internal institutional change, not external handouts.

Does democracy guarantee inclusive institutions?

Not automatically. Some democracies, like India, have made significant progress toward inclusivity. Others, like Venezuela before its collapse, held elections but allowed presidents to erode checks and balances, leading back to extraction. Democracy must be paired with strong institutions to be effective.

Conclusion: The Path Forward Begins with Institutions

*Why Nations Fail* offers a sobering yet hopeful message: poverty is not inevitable. Nations fail not because of fate, geography, or culture, but because of human-made systems that concentrate power and exclude the many for the benefit of the few. The good news is that these systems can be changed.

Real progress begins when ordinary people demand accountability, participate in governance, and build institutions that protect rights and reward effort. While there are no quick fixes, history shows that even deeply entrenched extractive systems can give way to inclusivity—when enough people insist on it.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?