In an era where global inequality persists and political instability affects millions, Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson’s seminal work Why Nations Fail offers a compelling explanation for why some countries thrive while others stagnate. The book, widely discussed in academic and policy circles, argues that the fate of nations is not determined by geography, culture, or ignorance—but by the nature of their institutions. This article unpacks the central ideas from the Why Nations Fail PDF, providing readers with a clear, practical understanding of its framework, real-world applications, and enduring relevance.

The Central Thesis: Institutions Over Geography

One of the most groundbreaking assertions in Why Nations Fail is the rejection of conventional explanations for national development. Many scholars have attributed economic disparities to climate, natural resources, or cultural values. Acemoglu and Robinson counter this by showing that neighboring regions with identical climates and cultures can experience vastly different outcomes based on institutional structures.

For example, the authors examine Nogales—a city split between Arizona (USA) and Sonora (Mexico). Despite shared geography, language, and ethnicity, the American side enjoys higher incomes, better healthcare, and stronger rule of law due to more inclusive political and economic institutions. This case illustrates that institutions, not location, are the decisive factor in national success.

“Poor countries are poor because they have extractive institutions designed to enrich the few at the expense of the many.” — Daron Acemoglu & James A. Robinson, Why Nations Fail

Inclusive vs. Extractive Institutions

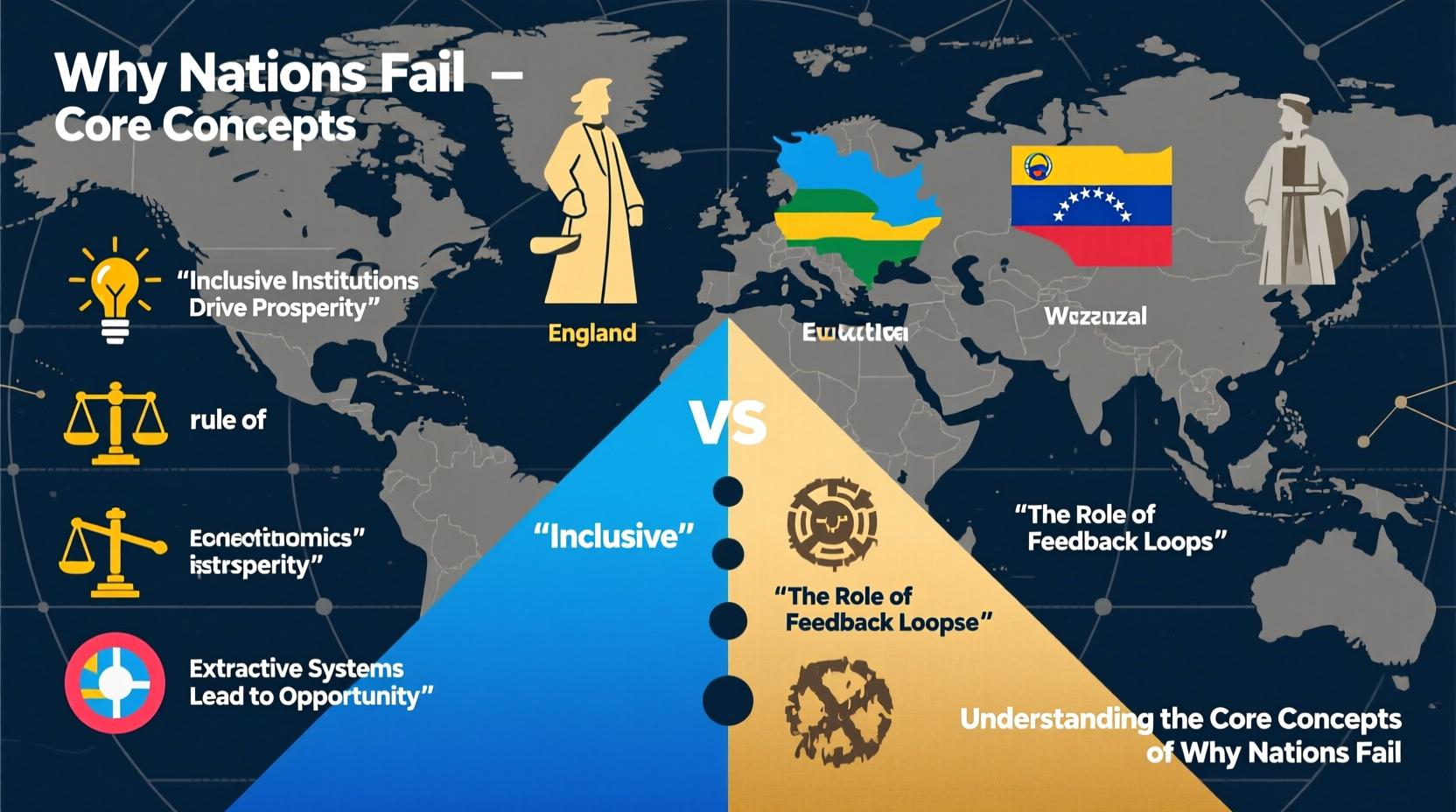

The core analytical framework of the book hinges on two types of institutions: inclusive and extractive.

- Inclusive institutions encourage broad participation in politics and economics. They protect property rights, allow market competition, and enable innovation. Examples include democratic governance, independent judiciaries, and accessible education systems.

- Extractive institutions concentrate power and wealth in the hands of a small elite. They suppress dissent, limit economic opportunity, and stifle upward mobility. These often manifest as autocratic regimes, state-controlled economies, or monopolized industries.

The interplay between these two systems determines long-term growth trajectories. Inclusive institutions create virtuous cycles: economic prosperity fuels political pluralism, which reinforces fair rules and further investment. Conversely, extractive institutions generate vicious cycles—elite control prevents reform, leading to stagnation and eventual crisis.

A Historical Timeline of Institutional Evolution

Acemoglu and Robinson support their thesis with historical case studies spanning centuries. Their analysis reveals that critical junctures—such as revolutions, colonial transitions, or technological shifts—can lead to divergent institutional paths.

- England’s Glorious Revolution (1688): Shifted power from monarchy to Parliament, laying the foundation for secure property rights and financial innovation—key precursors to the Industrial Revolution.

- Colonial Latin America: Spanish conquest established extractive systems like encomiendas, concentrating land and labor under elites. These structures persisted post-independence, hindering equitable development.

- Botswana vs. Zimbabwe: Both gained independence around the same time, but Botswana developed inclusive institutions through stable leadership and resource management, while Zimbabwe descended into authoritarianism and economic collapse.

- The Industrial Revolution: Flourished in England due to incentives for innovation; suppressed in absolutist regimes where elites feared creative destruction would undermine their control.

This timeline underscores a key insight: institutional change is neither inevitable nor linear. It requires sustained struggle by coalitions pushing for broader inclusion.

Real-World Case Study: South Korea and North Korea

No comparison better illustrates the book’s argument than the Korean Peninsula. After World War II, both North and South Korea were equally poor and war-torn. Yet within decades, South Korea emerged as a high-income democracy, while North Korea remained impoverished and repressive.

The divergence stems directly from institutional choices:

| Aspect | South Korea | North Korea |

|---|---|---|

| Political System | Democratic republic with competitive elections | Totalitarian dictatorship |

| Economic Model | Market-oriented with private enterprise | State-controlled command economy |

| Innovation Environment | High R&D investment, tech exports (e.g., Samsung) | Isolated, minimal innovation |

| GDP per capita (2023 est.) | ~$35,000 | ~$1,700 |

The contrast shows that even shared history and culture cannot overcome the drag of extractive institutions. South Korea embraced reforms that empowered citizens economically and politically, creating feedback loops of progress. North Korea, by contrast, entrenched elite control, suppressing any challenge to the status quo.

Common Misconceptions About Development

The book challenges several widely held beliefs about why nations succeed or fail. Understanding these myths helps clarify the true drivers of prosperity.

- Myth: Rich countries got wealthy because of superior knowledge or technology. Reality: Technology spreads easily, but without inclusive institutions, it won’t be adopted or improved upon.

- Myth: Dictatorships can deliver growth efficiently. Reality: While some authoritarian regimes achieve short-term growth (e.g., China), sustainability depends on whether institutions eventually become inclusive.

- Myth: Foreign aid alone can lift nations out of poverty. Reality: Aid often props up corrupt elites in extractive systems, reinforcing dependency rather than transformation.

Actionable Checklist: Evaluating National Institutions

To apply the insights of Why Nations Fail in practice, consider using this checklist when studying a country’s development prospects:

- Are political leaders selected through free and fair elections?

- Do citizens have enforceable property rights?

- Is there access to credit and entrepreneurship opportunities for all groups?

- Are state institutions transparent and accountable?

- Does the legal system treat everyone equally?

- Are there mechanisms for peaceful political change?

- Is education broadly accessible and of high quality?

If most answers are “yes,” the nation likely has inclusive foundations. If not, structural barriers—not lack of effort or resources—are probably holding back progress.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can extractive institutions ever lead to growth?

Yes, temporarily. Authoritarian regimes like the Soviet Union or modern-day China have achieved rapid industrialization by mobilizing resources centrally. However, such growth often plateaus because fear of innovation and political threats discourages long-term investment and adaptation.

Is democracy necessary for inclusive institutions?

While democracy is not the only path, it is the most reliable mechanism for sustaining inclusivity. Without electoral accountability, elites have little incentive to share power or invest in public goods.

What can individuals do to promote inclusive institutions?

Citizens can advocate for transparency, participate in civic life, support independent media, and hold leaders accountable. Change often begins with grassroots movements demanding fairness and representation.

Conclusion: A Call to Understand and Act

Why Nations Fail is more than an academic treatise—it is a call to recognize that prosperity is not preordained. The gap between rich and poor nations is not rooted in immutable traits but in human-made systems that can be reformed. By understanding the power of institutions, readers gain not just insight, but responsibility. Whether you're a student, policymaker, or engaged citizen, the lessons from the Why Nations Fail PDF offer a roadmap for building societies where opportunity is shared, innovation rewarded, and dignity upheld.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?