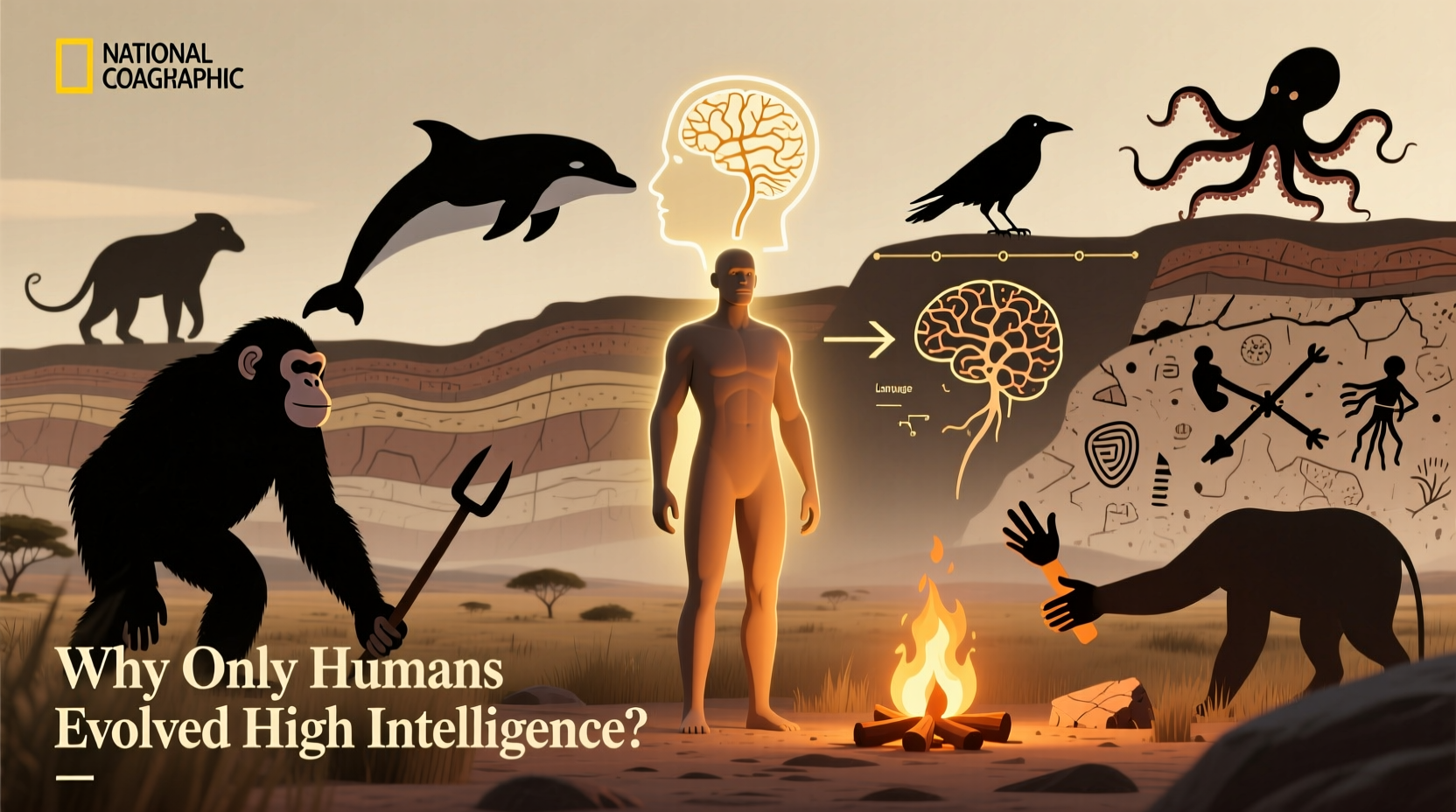

Among the millions of species on Earth, only one has developed the capacity for abstract reasoning, complex language, long-term planning, and technological innovation: Homo sapiens. While many animals display forms of intelligence—dolphins navigating social hierarchies, crows solving multi-step puzzles, or octopuses escaping enclosures—none have reached the cognitive threshold that defines human-level intelligence. The question remains: why did high intelligence evolve in humans but not in other species? The answer lies at the intersection of evolutionary biology, environmental pressures, social complexity, and metabolic trade-offs.

The Evolutionary Path to High Intelligence

Intelligence is not an inevitable outcome of evolution. It is a costly adaptation, requiring significant energy and time to develop. The human brain consumes about 20% of the body’s energy despite making up only 2% of its weight. For such a trait to evolve, the benefits must outweigh the costs over generations.

In early hominins, several key shifts laid the foundation for enhanced cognition. Bipedalism freed the hands for tool use, which in turn created selective pressure for better motor control and problem-solving abilities. As climate fluctuations transformed African landscapes from dense forests to open savannas, early humans faced unpredictable environments where adaptability became crucial. Those with greater cognitive flexibility—able to remember food sources, predict seasonal changes, and cooperate under stress—were more likely to survive and reproduce.

“Natural selection favors intelligence not because it’s inherently superior, but when it solves real survival problems better than alternatives.” — Dr. Robert Sapolsky, Neuroendocrinologist and Evolutionary Biologist

Social Complexity as a Cognitive Driver

One of the most compelling theories explaining the rise of human intelligence is the Social Brain Hypothesis. Proposed by Robin Dunbar, this theory suggests that the primary challenge driving brain expansion was not environmental mastery, but managing increasingly complex social relationships.

Living in larger groups offered protection and improved resource sharing, but also introduced new challenges: tracking alliances, detecting deception, forming coalitions, and navigating status hierarchies. The ability to understand others’ intentions—known as theory of mind—became a powerful evolutionary advantage.

Dunbar’s research shows a strong correlation between primate neocortex size and average group size. Humans, with the largest relative neocortex, maintain stable social networks of about 150 individuals—the so-called \"Dunbar’s number.\" This intricate web of relationships demanded advanced communication, memory, and emotional regulation, all of which pushed cognitive evolution forward.

Language and Cumulative Culture

While some animals communicate, only humans possess recursive, symbolic language capable of conveying abstract ideas across time and space. Language enabled knowledge transfer beyond individual experience, allowing each generation to build upon the discoveries of the last—a phenomenon known as cumulative culture.

This cultural ratchet effect meant that innovations like fire control, tool refinement, and eventually agriculture could be preserved, improved, and shared. Unlike genetic evolution, which operates slowly over millennia, cultural evolution can accelerate change within decades.

No other species exhibits this degree of cultural accumulation. Chimpanzees may learn to crack nuts with stones, but they don’t refine the technique over generations. Human children, by contrast, absorb vast amounts of information through language and observation, enabling exponential learning.

| Feature | Humans | Other Intelligent Species |

|---|---|---|

| Symbolic Language | Full syntactic structure, infinite combinations | Limited signals (e.g., bee dances, alarm calls) |

| Cumulative Culture | Technological progress over generations | Minimal improvement over time |

| Teaching Behavior | Active instruction and scaffolding | Rare; mostly observational learning |

| Long Juvenile Period | Extended childhood for brain development | Shorter dependency periods |

Metabolic and Developmental Trade-offs

High intelligence comes with biological compromises. The human brain requires years of postnatal development, resulting in an unusually long childhood. Human infants are born highly altricial—helpless and dependent—due to the constraints of bipedal pelvis anatomy and the need for large brains.

This extended period of vulnerability necessitated strong parental investment and cooperative breeding, where multiple group members help raise offspring. Such social structures further reinforced bonding, communication, and emotional intelligence.

Moreover, the energy demands of the brain likely influenced dietary evolution. The inclusion of nutrient-dense foods—meat, cooked tubers, and later dairy—provided the caloric surplus needed to sustain larger brains. Cooking, in particular, increased digestibility and reduced the energy spent on chewing and digestion, freeing metabolic resources for neural development.

Step-by-Step: How Intelligence Emerged in Humans

- Bipedalism: Freed hands for manipulation and tool use.

- Dietary Shifts: Increased meat consumption and cooking provided energy for brain growth.

- Social Expansion: Larger groups created pressure for better communication and relationship management.

- Language Development: Enabled knowledge transfer and coordination.

- Cumulative Culture: Innovations built across generations, accelerating adaptation without genetic change.

Why Didn’t Other Species Follow the Same Path?

Several intelligent species come close—elephants with their empathy and memory, parrots with vocal mimicry and problem-solving, dolphins with self-awareness—but none crossed the threshold into full symbolic thought and open-ended innovation. Why?

First, ecological niches matter. Many species thrive without needing advanced cognition. A cheetah succeeds through speed, not strategy. An octopus survives through camouflage and reflex intelligence, not long-term planning.

Second, evolutionary pathways are constrained by history. Birds evolved from dinosaurs with different brain architectures. Their intelligence is distributed differently—corvids use pallial regions analogous to the mammalian cortex, but lack layered neocortices. Structural differences limit certain types of abstract processing.

Third, there’s no guarantee that intelligence leads to long-term survival. Dinosaurs dominated for 180 million years without human-like cognition. Humans, while dominant now, face existential risks from their own technology and environmental impact.

“We’re not the pinnacle of evolution—we’re just one experiment among millions. Intelligence is rare because it’s risky, expensive, and only useful under very specific conditions.” — Dr. Frans de Waal, Primatologist and Ethologist

Frequently Asked Questions

Could another species evolve human-level intelligence in the future?

Possibly, but unlikely under current conditions. Evolution doesn’t aim toward intelligence. Even if environmental pressures favored smarter animals, the combination of social structure, diet, developmental timeline, and genetic potential required is extremely rare. Human-level intelligence arose from a unique confluence of factors unlikely to repeat identically.

Do whales or dolphins have hidden intelligence we don’t understand?

Yes, likely. Cetaceans have large brains and complex social systems. Some researchers believe their communication may involve syntax and meaning beyond our current decoding ability. However, without manipulative limbs, they cannot build tools or externalize knowledge the way humans do, limiting visible technological expression.

Is artificial intelligence proof that intelligence can emerge outside biology?

In a functional sense, yes—but not through natural selection. AI is designed, not evolved. It lacks intrinsic motivation, consciousness, and embodied experience. While AI can outperform humans in specific tasks, it does not “understand” in the biological, emotional, or evolutionary sense that human intelligence does.

Conclusion

Human intelligence did not arise because we were destined to be the smartest species, but because a series of interlocking pressures—environmental instability, social complexity, dietary opportunity, and reproductive strategy—favored incremental gains in cognitive ability over millions of years. Each step was small, shaped by immediate survival needs, yet collectively they led to something unprecedented.

Understanding why only humans evolved high intelligence reminds us that our minds are not magical, but the product of chance, necessity, and deep time. This awareness should inspire both humility and responsibility. Our intelligence gives us power over the planet, but also the duty to use it wisely—for ourselves, other species, and future generations.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?